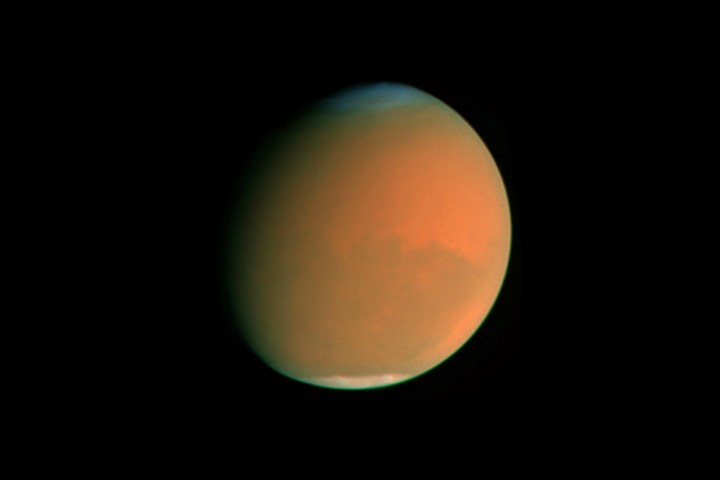

“Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kid; in fact, it’s cold as hell.” So sang Elton John in 1972’s “Rocket Man,” one of the greatest (and only) pop hits ever to be written about the loneliness of space exploration. It’s a valid point — and one which scientists have been seeking to address ever since. With everyone from Elon Musk to the good folks at NASA talking about the creation of a Mars colony, finding some way to make the Red Planet habitable has become a top priority. And Harvard University scientists think they may have found a way to do it.

The newly proposed approach comes shortly after what appeared to be the end of the dream for terraforming Mars. Terraforming describes the hypothetical process of artificially transforming a planet so that it closer resembles Earth, thereby allowing it to support life. Unfortunately, a NASA-sponsored study from last year concluded that it most likely wouldn’t work.

Simply put, Mars does not have enough plentiful enough carbon dioxide supplies could practically be put back into the atmosphere to warm the planet. Processing all available CO2 sources available on Mars would increase atmospheric pressure to just 7% of that on our own planet. As a NASA press release stated: “Transforming the inhospitable Martian environment into a place astronauts could explore without life support is not possible without technology well beyond today’s capabilities.” Mars will, to return to Elton John’s “Rocket Man”, remain far too cold to raise a kid.

But this is where Harvard’s idea comes into play. They suggest that an insulating material, referred to as a silica aerogel, could be used to make growing plants on Mars feasible, thereby helping sustain life. It wouldn’t be necessary to cover the entire planet for this to work, either.

“We propose to use thin layers of silica aerogel to heat the surface of Mars to the melting point of liquid water, in order to create habitable conditions there,” Robin Wordsworth, Associate Professor of Environmental Science and Engineering at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School Of Engineering And Applied Sciences, told Digital Trends. “The silica aerogel warms the surface due to the solid-state greenhouse effect. This effect arises naturally on the Martian surface in CO2 ice and is responsible for the enigmatic dark streaks we see near the poles from orbit. Silica aerogel is an amazing material that is optimal for our purpose because it is translucent and extremely light, but it blocks UV radiation and is incredibly effective at trapping heat.”

It might just work

Sure, it’s still a hypothetical concept, but Wordsworth and fellow collaborators have reason to believe that it might just work. To demonstrate their idea, they erected a solar simulator in a laboratory to replicate the flux and spectrum of Martian sunlight. They placed sheets of aerogel over dark material, measured the resulting solar flux with a pyranometer, and then recorded the temperature using an array of thermistors and a thermal camera. After that, they used a computer model incorporating observed Mars climate data to simulate the evolution of a silica aerogel habitable zone on the surface over several Mars years.

“We plan to increase the complexity and realism of our lab experiments and computer simulations to address some of the remaining challenges such as controlling pressure variations,” Wordsworth continued. “We also plan to perform field studies at a Mars analogue site in order to test this mechanism outside of the laboratory. Eventually, of course, if everything goes well we would like to test this on the Martian surface directly.”

This is, of course, where things will get a bit trickier. It is feasible, though, given the number of missions planned to Mars in the coming years. This includes launches by the U.S., China, Japan and other countries, in addition to a bevy of proposed private company launches. Should all go to plan, hitching a ride on a Mars mission in the 2020s will be easier than picking up an Uber. (Well, perhaps not quite so easy, but certainly more so than it’s ever been in the past.)

There is still plenty to consider, though — and, yes, part of that includes the threat of disrupting some form of alien life. There are few worse ways of introducing ourselves to other intelligent life in the universe than by littering their home planet. “The main risk is associated with planetary protection,” Wordsworth continued. “We haven’t yet found any life on Mars, but it could still be conceivably hidden in some subsurface niches. When we build habitats on Mars, we need to be careful not to interfere with this life in any way if it does exist.”

Other future challenges include ensuring that there are enough nutrients on the surface of Mars and controlling for any potential toxins.

Nonetheless, this is promising, exciting work. We hesitate to throw around the word “practical” when it involves making another, currently un-livable planet livable, but there’s still cause for quiet excitement and optimism. Maybe Elton John should start rewriting some of the lines of “Rocket Man” just in case…