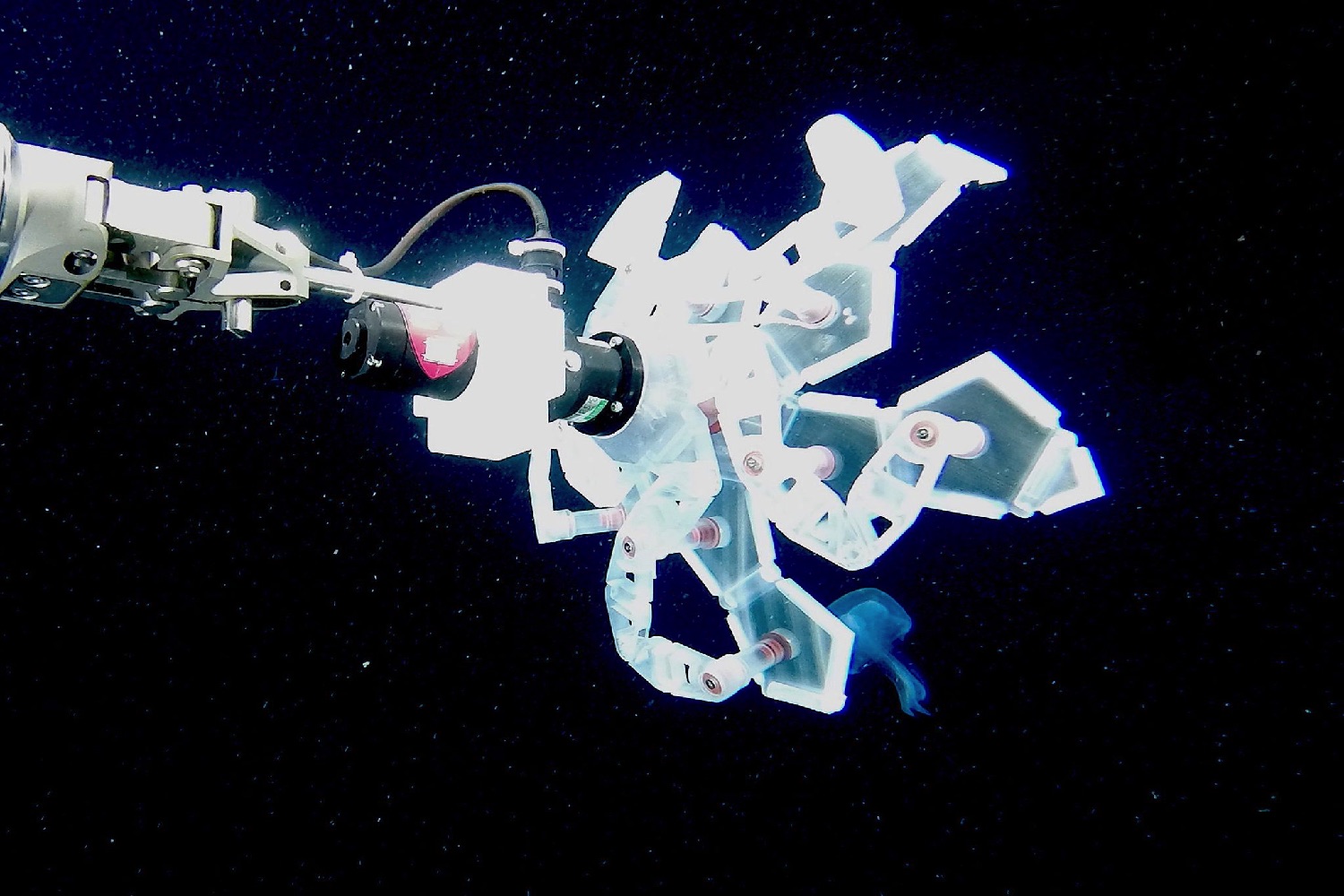

There are plenty of people out there who base their research on studying robotics. However, robots can help us carry out study in other fields, too — as a new folding grabber robot developed at Harvard University makes clear. Harvard’s innovative RAD robot (that’s short for “Rotary Actuated Dodecahedron,” although it’s pretty rad as well) is designed to be able to perform delicate feats, such as catching underwater creatures with ease and, crucially, without injuring them in the process.

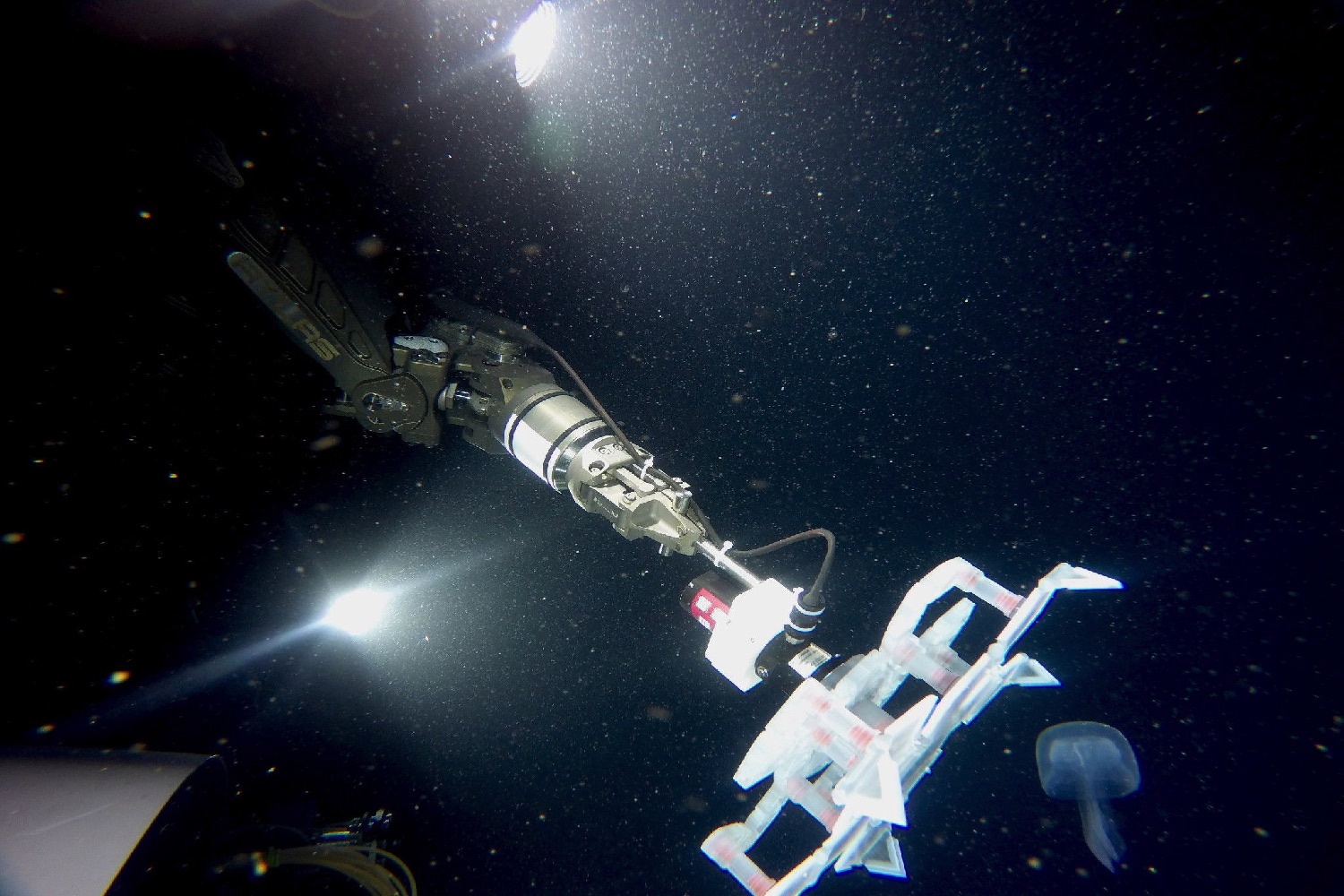

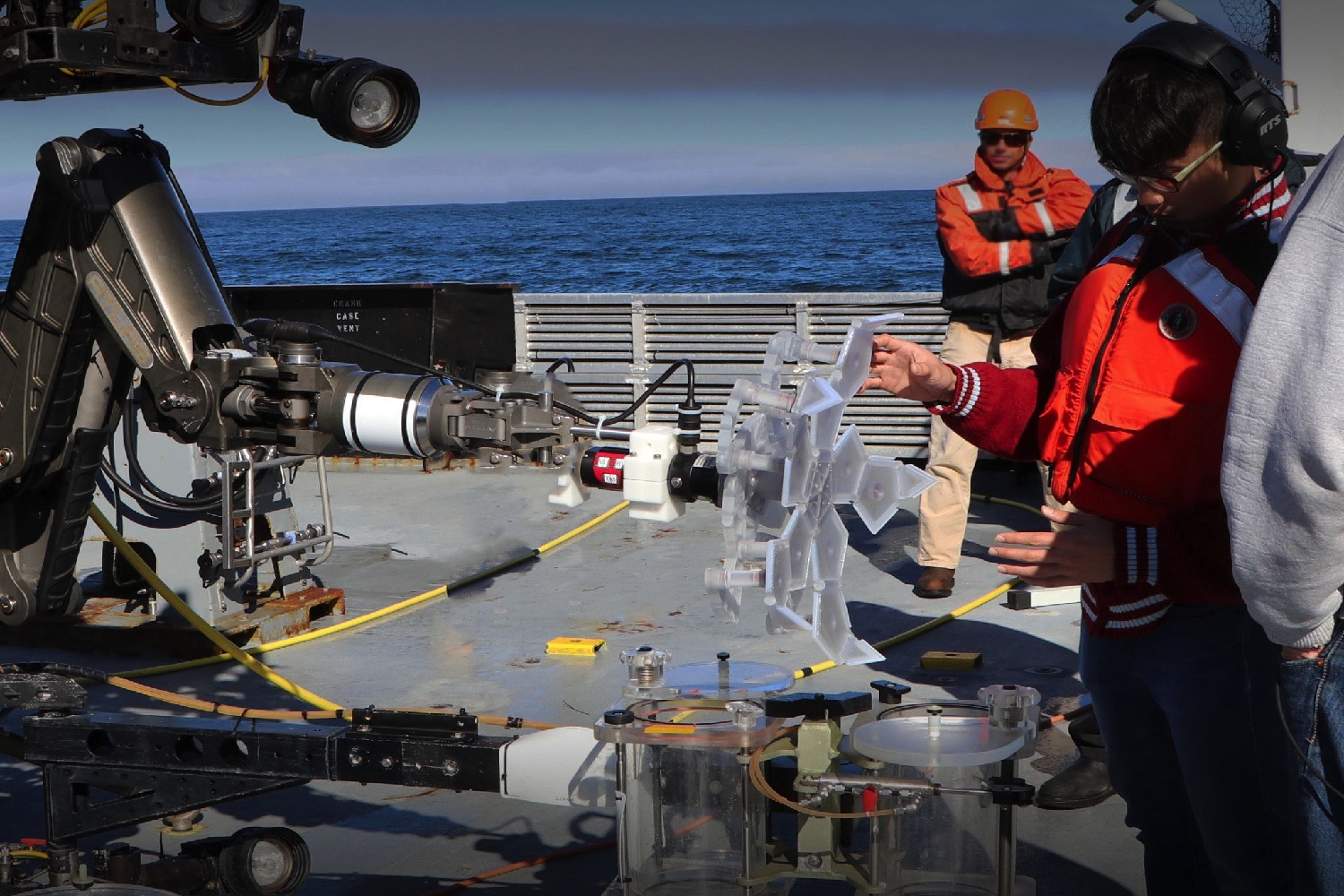

It does this using what can be described as a Poké Ball on a robot arm, capable of closing over an object without damaging it. It has so far been put through its robotic paces in an aquarium and deep in Monterey Canyon, off the coast of central California, where it was used to catch a jellyfish, a squid, and an octopus.

“We first tested the RAD sampler at Mystic Aquarium to see if could catch jellyfish,” Zhi Ern Teoh, a postdoctoral researcher who worked on the project, told Digital Trends. “We were concerned that as fluid is expelled during the closing phase, the flow would also push the jellyfish away. Turns out, the speed at which we close is slow enough such that jellyfish remain in the grab zone.”

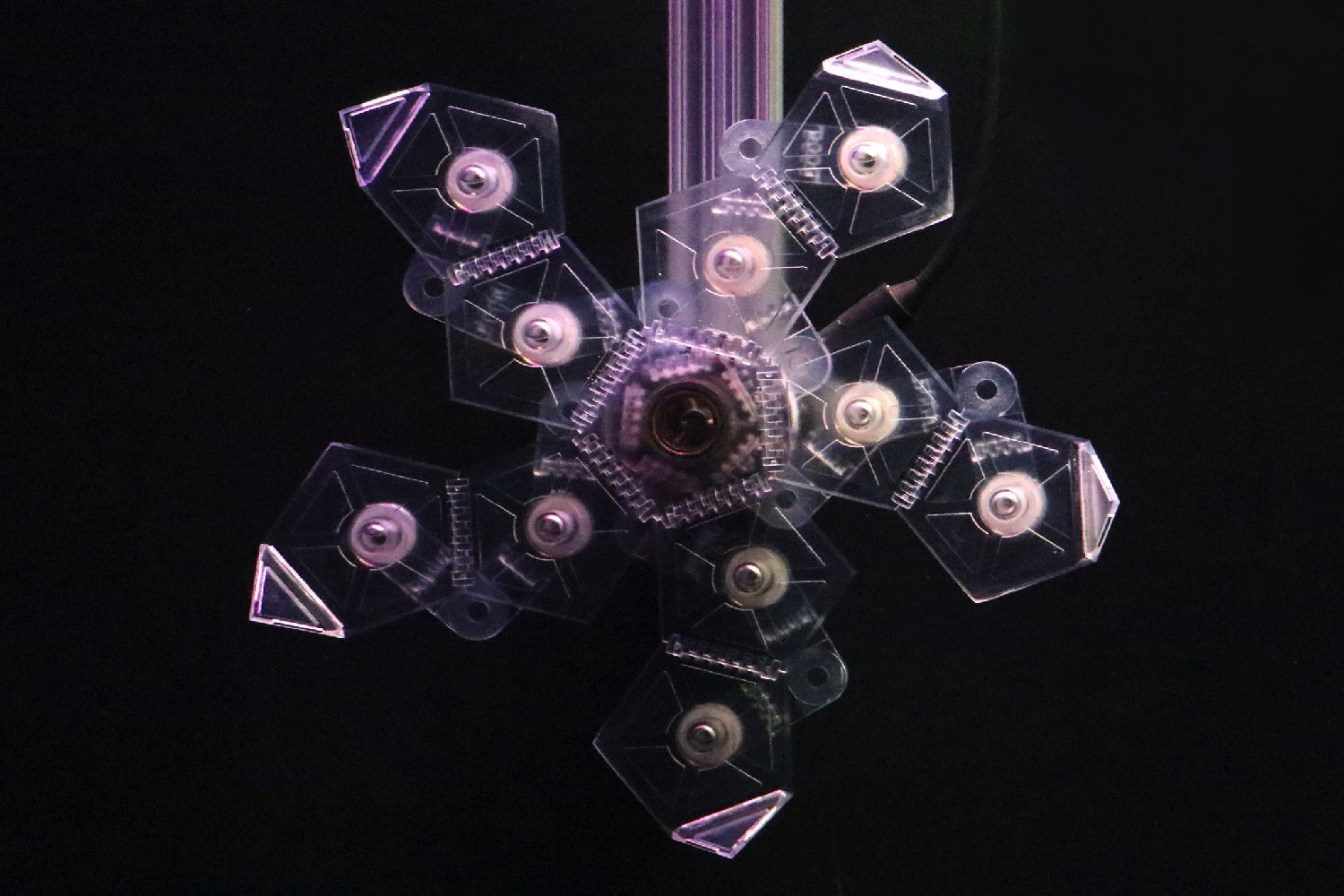

From a technical perspective, the aspect of the project that’s most interesting is the origami-like folding shape of the Poké Ball part of the robot. The team was able to develop a way to fold 3D shapes from a 2D net using only a single actuator.

“For example, imagine unfolding a cube,” Teoh continued. “The net of the cube would be a cross made of six squares. We then build another layer of linkages on top of the net. This transforms the net from a five degree of freedom system to a one degree of freedom system. This is exciting because now we can potentially construct 3D shapes from its 2D net using only one actuator. Minimizing the number of actuators is key because incorporating actuators is a relatively more complex engineering task; you have to figure out ways of attaching, powering, sensing, and coordinating the folds. Therefore even though the system of linkages look more complex, they consist entirely of revolute joints which are mechanically much simpler.”

Next up, Teoh said the team hopes to develop a version of the grabber that’s constructed with a more rugged material, such as titanium or stainless steel. They also want to make it more autonomous by incorporating cameras and pressure sensors to transform it from nifty proof-of-concept to fully realized tool for marine biologists.

A paper describing the work was recently published in the journal Science Robotics.