“We said ‘It’ll be May 10,” and we picked a day,” CEO Rob Lloyd confessed. “And three weeks ago, it wasn’t done.” Sure, the world-class engineers had the science down, developed a reliable propulsion system, and ran the numbers, but physical testing? Not quite yet.

Despite endeavoring to build a futuristic system that seems more at home on the pages of an Isaac Asimov novel than in the Nevada desert, the company felt so confident that it invited tech journalists from every major publication to see the thing in person. Like Babe Ruth calling his shot, Hyperloop One took a calculated leap of faith that — like Babe’s — paid off in spades.

After standing before the steel test track outside Sin City on the day Lloyd promised to unveil it, I can vouch that the first Hyperloop prototype is very much real. And the future of transportation technology is quite literally riding on it.

The long story

Lloyd and Hyperloop One co-founders Shervin Pishevar and Brogan BamBrogan may have laid the first Hyperloop tracks, but they didn’t hatch the idea. Back in 2013, Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk introduced the world to both the Hyperloop concept and terminology when he published an ambitious white paper. The enigmatic inventor imagined a 750mph mag-lev train that would rocket passengers from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 35 minutes within a vacuum tunnel.

“If you have an idea, throw it in here and we’ll help you develop that idea.”

A public accustomed to waiting that long just for airport security, or a commute across town at rush hour, was enraptured.

Rather than forming his own company to pursue the dream, Musk published his ideas for anyone to use, and several competitors with confusingly similar names rushed to fill the void. In the years that followed, they took turns publishing enthusiastic press releases trumpeting their behind-closed-doors achievements. But how much of it was genuine progress? The dueling companies gave a cynical public and journalists plenty to doubt.

What’s in a name, anyhow?

In the wake of Musk’s announcement, co-founders Shervin Pishevar and Brogan BamBrogan dubbed their company Hyperloop Technologies. Another company with the same ambitions snagged a strikingly similar name: Hyperloop Transportation Technologies. This ensuing confusion turned out to be the company’s first challenge.

“I think it’s been difficult for you, and others, to discern the difference between our company and another company,” Rob Lloyd told Digital Trends. Ultimately, the company changed its name to Hyperloop One the day before the test run – a name the team hopes reflects its priorities.

“We actually took a step back and thought about what was important to us. We talked about the things that were important to the team, and they were, first and foremost, ‘the smartest people and the best minds that are working in unity to make this happen.’”

So what were those three weeks leading up to the event like? Lloyd credits Hyperloop One Senior VP of Engineering Josh Giegel for working miracles. “I love the pressure!” Giegel chimes in during our interview.

“I love the pressure!”

“We set out, Brogan and myself, from the early days in the garage, to build a team of really talented individuals,” Giegel told Digital Trends. “We were fortunate enough to know what a team like SpaceX could do with limited resources and big ambitions. We knew if we built a team like that here, we could do those types of things and great engineers respond really well to very specific dates.”

While the Hyperloop One desert testing site typically consists of five full-time workers, at least 25 people worked around the clock there for the six weeks leading up to the event. On May 11, it was show time.

Pressing the button

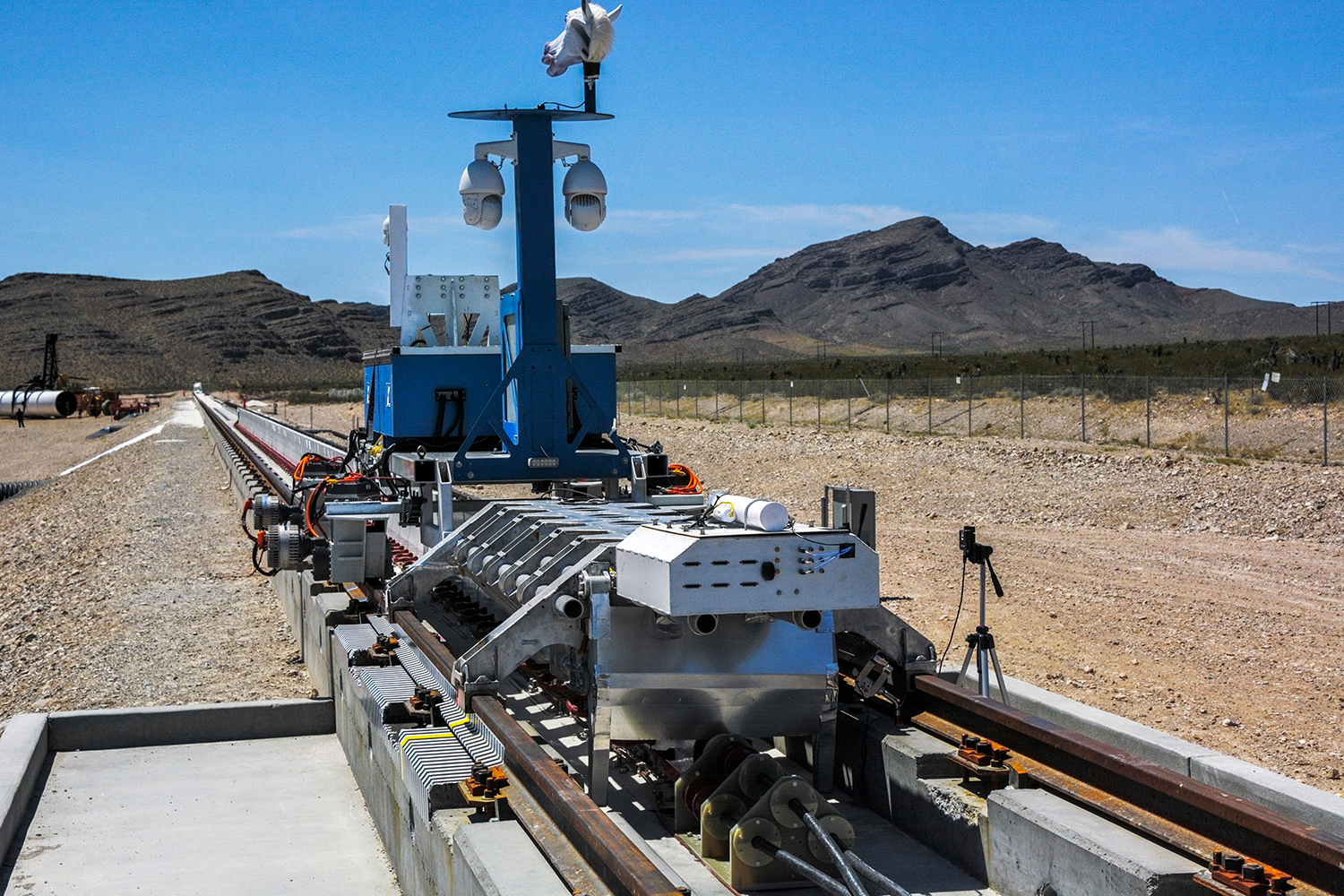

As Brogan pumped up the anxiously awaiting crowd, he warned them to put their phones and cameras down. If you blink, you’ll miss it, even though a successful test for Hyperloop One simply meant propelling its test sled down the track a short distance, not having it move at breakneck speeds.

Despite sitting just a couple hundred feet away from the surprisingly small sled on bleachers, all eyes moved to a zoomed feed as the team rattled off a short 10-second countdown, like a rocket launch. Three. Two. One.

The crowd held its collective breath as the aluminum sled shot down the Hyperloop test track and plowed to a sand-aided stop roughly 100 yards later.

Though it glided forward whisper quiet and lasted a mere matter of seconds, the sled elicited riotous applause from the crowd. Engineers passed sheepish glances at each other before one brave soul stood up and began yelling. The rest quickly followed suit, having no doubt earned a few moments to cheer.

Hyperloop One’s test module hit roughly 2.5Gs of acceleration before braking in the sand – more than a Bugatti Veyron as it rushes to 60mph in 2.4 seconds. Sure, it didn’t get anywhere near the proposed final speeds of around 750 miles per hour, but for the first time in the Hyperloop’s short history, it existed somewhere other than on paper. Hyperloop One: 1. The field: 0. To the casual observer, a sled was uneventfully propelled down a short track. To Hyperloop One, it was much more complex than that.

What’s next?

“This is a complicated system and we’ve got some brilliant people that led this team,” Lloyd explains. “It’s a one-of-a-kind, linear-electric motor that’s custom-designed by the team, and the materials and the manufacturing process is hard.”

Producing white stator blocks — electromagnetic propulsion elements that propel and elevate the test sled — was the biggest barrier at the team prepared for the event. With an open-air short track test under its belt, Hyperloop One now plans on doubling the amount of stators installed into the track, while gearing up for full-systems testing this coming fall and winter.

A string of continued successes will allow Hyperloop One to begin constructing a small version of a finished Hyperloop, large white tubes and all.

Pitch in

As it toils away internally, the company has also reached out to enthusiasts with the Hyperloop One Global Challenge. Think of it as an initiative to crowdsource the greatest Hyperloop ideas from the sharpest minds all over the world. Now through September 15, Hyperloop One will gather any viable submission sent its way. Those entries will be whittled down to a field of just 12 finalists by January 2017. Then in March, three finalists will be selected.

“It’s a one-of-a-kind, linear-electric motor that’s custom-designed by the team.”

“I found out within months of starting at Hyperloop One that there were dozens and dozens of people, companies, organizations, and teams that had been working for years to solve transportation problems,” Lloyd said. “They had ideas but they didn’t have the toolkit or the technology to make it happen. The Hyperloop One Global Challenge is a reach-out from us to say ‘Come on guys, if you have an idea, throw it in here and we’ll help you develop that idea.'”

If the company wants to produce a working Hyperloop system in the next three to five years, Lloyd acknowledges, it’s going to need all the help it can get.

Sound too ambitious? The ball is now rolling. Open-air propulsion testing was a giant step toward making Hyperloop technology available for cargo transports in as few as three years, and passenger-ready in just five – by 2021, according to the company.

Can they pull it off? Some cynicism is natural. We’re talking about a fully functioning transportation system flinging people 750 miles per hour, in a vacuum-sealed tube. But we traveled to Las Vegas with a pocketful of doubts, and giddily left our jaws on the floor after witnessing a truly disruptive technology.

On Tuesday night, Lloyd asked a panel of industry specialists to give one word to describe the Hyperloop in 10 years. One said “verbified,” as in, “I Hyperlooped to work today.” Another said “bold.” but Lloyd himself said it best when we asked him the same question.

“Amazing … simply amazing.”