A new imaging technique shows promise at better identifying the telltale signs of disease, according to results of a new study. Called HySP or Hyper-Spectral Phasor, the technique improves on a basic technique used by medical researchers: Molecules glow differently under various wavelengths of light, notably fluorescents (think black lights), and layering these types of images together provides a picture of the molecule’s health. Doing so is slow and labor intensive, however. The new algorithm makes it easier.

“By looking at multiple targets, or watching targets move over time, we can get a much better view of what’s actually happening within complex living systems,” said Francesco Cutrale, a postdoctoral fellow at USC’s Translational Imaging Center, which specializes in imaging biological systems.

Such a technique is critical, especially when finding the beginnings of diseases can seem like finding a needle in a haystack. By monitoring changes over time, researchers could get a better understanding of how a disease behaves.

HySP can do this in one pass; other systems perform each one seperately before using algorithms to piece the scans together. That process is time consuming and expensive, and requires a good deal of computing power.

“Imagine looking at 18 targets,” Cutrale said. “We can do that all at once, rather than having to perform 18 separate experiments and try to combine them later.”

Even better, HySP’s algorithm is built to filter out interference but has been shown to be effective in separating that noise from weak signals. Here’s that “needle in a haystack” analogy again — this could be vital in early detection of diseases or health issues leading to more effective treatment.

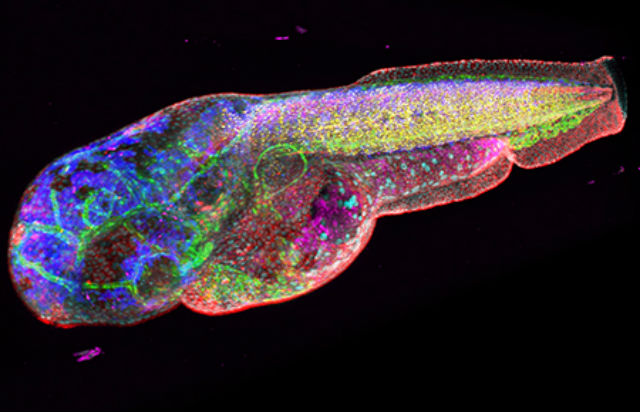

Researchers at USC have tested the concept on zebra fish so far. In the future, the research team plans to test HySP on humans, specially members of the military who have been exposed to chemicals and materials damaging to their lungs while in combat. A tiny probe with a flourescent light will be lowered into their lungs to capture images of the surrounding tissues. These pictures will be compared with those of healthy lungs, and researchers hope they’ll be able to spot a difference.

If successful, they hope the technology will be useful in practice to diagnose lung disease. The researchers note that their technology could be used in cell phone cameras as well: take a picture of a lesion and a doctor could tell you if it’s potentially cancerous. Now that’s a picture with talking about.

The study was published in the January 9 edition of Nature Methods.