Check out Part I and Part II in our series about life in the year 2020.

Our cities are a mess. Based on grids of pavement for devices of transport that pump poisonous fumes into the atmosphere, they and their inhabitants are slowly but inexorably being choked into submission. Many of them are rotting from the core – their eroding downtowns often unattainable in heavy traffic from the distant, sprawling suburbs that surround them.

And in those suburbs, life isn’t necessarily much better. Many are just as bereft of green space, and most are so expansive that one needs an automobile just to buy a gallon of milk. What’s worse, some of us have been convinced we’d be better off grabbing that gallon of milk in a beast like a Ford Excursion or Hummer. As for entertainment or a sense of community, well, there’s always the food court at the local mega-mall – if you can find a parking space.

A bleak outlook? Admittedly, yes, and certainly not all of our cities are in such a state of disrepair. Nonetheless, our current urban model is far from the ideal for a number of reasons, Our cars continue to pollute and clog our environments, our urban footprints – not to mention our landfills – continue to expand, and our retail, entertainment, and social zones continue to centralize. “They paved paradise to put up a parking lot.” Joni Mitchell may have written the words in 1970, but they were never more apropos than today.

With all of this in mind, but also some potential solutions, we embark on Part III of our look at life in the year 2020. In Part I, we went all atmospheric on you in our look at cloud computing and future computing in general. In Part II, we speculated how research in the fields of biotech, genetic, and nanotech science will likely afford you a better, longer life. But here in Part III, we hit where we live (a good many of us anyway) with an overview of what we might experience and begin to experience in our cities a decade from now, as seen through the eyes of several people who are a lot closer to the subject then we are.

The Future of the Car

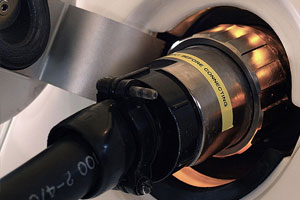

We start with what many perceive to be Public Enemy Number One: the automobile. Today’s car is naughty for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the gasoline-based, combustion-powered engine that propels it down the street. Not only does that engine foul the environment, but it and all its associated machinery take up a ton of

But changes are already afoot. Sales of large cars and SUVs have plummeted in the past few years. Many drivers have recently opted for smaller cars or hybrid technology. Others lucky enough to live close to their places or work are taking the two-wheel bicycle approach. And of course, rapid transit has never been so popular.

But what of the future of the four-wheeled pod we know as the car? It’s clear, given the emissions, the price of gasoline, the limited supply of oil, and numerous other factors, that pure gasoline-powered combustion engine vehicles are on the way out. But what will ultimately replace it?

Hybrids, Green Diesels, and Solutions on the Horizon

Gas- and diesel-electric hybrids are currently the rage of the alternative fuel market. The latest model of Toyota’s Prius has scored critical praise everywhere it’s been released, and world-level car shows are filled with hybrid prototypes. Volkswagen’s just-announced L1 diesel-electric hybrid concept car, targeted for a 2013 production date, is said to achieve an astonishing 189 MPG.

So rosy are long-term forecasts for the electric car that Carlos Ghosn, the big cheese over at French automaker Renault, says they will “account for 10 percent of the global market in 10 years.” Tesla’s business development chief, Diarmuid O’Connell, went one huge step further when he recently prognosticated that pure electric vehicles will make up 30 percent of the total market within the decade. At the same time, several research firms put that number at just one or two percent.

The Case for Hydrogen Fuel Cells

So, what’s the ultimate solution? What will we see gracing our roadways by 2020 and beyond? Gary Golden, lead futurist with New York-based foresight and innovation organization Future Think and consultant to firms such as DuPont and CitiGroup, talked to us recently and emphasized that hybrids, while likely with us for some time, are most definitely not the technology of the future. “They do nothing but add manufacturing costs and complexity. There is no value to either side.”

Is the Plug-In Electric Car Doomed?

He does not, however, believe we’ll see a massive shift away from combustion engines within the next decade. “Not a chance. Oil is the dominant fuel well beyond 2020. It is a simple market share extrapolation. The conversion from liquid fuels and combustion engines to electric motors powered first by batteries then hydrogen fuel cells will take years to emerge and at least two decades for a full market share transition.”

Golden brings up another interesting point, and one that video gamers the world over can relate to: automakers have conditioned us to expect a new iteration of each model in their lineup, often with very little real upgrades, every single year. “The real problem is the cost of building cars. And new car models drive revenue. The auto industry needs to move to making money on every mile and every minute spent in car, not just selling new cars. This isn’t a sexy concept for some readers. But the reality is that the revolution is how we build cars, not fuel them.”

No Silver Bullet: The Drawbacks of Hydrogen

Some skeptics agree with Golden and his plug-in negativity, pointing out that hundreds of thousands of plugged-in automobiles could overwhelm grids and generating plants, and that large-scale production could send lithium prices skyward. Others, like Stephen Rees, veteran of the UK Department of Transport and British Columbia Ministry of Energy and now a highly-regarded socio-political blogger, aren’t nearly so high on hydrogen. “Hydrogen is merely a way of storing electricity, and one that is highly inefficient. Hydrogen that is a by-product of chemical processes is not pure enough for fuel cells, so it is made by electrolysis of water. Hydrogen is very difficult to store and handle. No one has yet come up with a cheap way to make or store hydrogen, or a convenient way to put it into a vehicle.”

Golden also concedes the road ahead will be rough. “Electric motors are more efficient than combustion engines. Electric vehicles standing still do not waste energy like combustion engines. The overall energy savings are significant. But people who act as if we can find a silver bullet are ridiculous. This is a weak case against the reality that we are going to go through phases of change.”

The Future of Public Transit

Cleaner cars are one thing. Arguably just as important to the immediate future of our cities are alternatives to the automobile. Visualize for a moment your immediate neighborhood and the town where you live. Notice that none of it – with the exception of undeveloped lands – is free from the influence of the car. Notice how much raw land – from one-lane alleys to eight-lane thoroughfares, from service stations to seemingly omnipresent parking lots – is dedicated not to people, but to comparatively large vehicles.

“Mass transport is 90 percent a question of managing streets, neighborhoods, and cities (land uses), and only 10 percent technology. High-speed rail, I have my doubts about. It works well in Japan, France, and Spain because road fuel is expensive, freeways are tolled, and until twenty years ago, the price of an air ticket was high. And above all, because millions of people live within a half hour of a station by mass transit.”

Where Trains Fear to Tread: Personal Urban Vehicles

Schipper favors an integrated, top-down approach. “The most interesting developments will be real bus rapid transit, a kind of surface metro, together with real estate, residential, and commercial development at major nodes. The sleeper to me will be communities of rather high density built for slow, small, safe electric vehicles that don’t need to go fast – and can’t.”

Rees contends that there’s no magic bullet that meets all needs. “Buses need priority in traffic. The tram – or streetcar – will see a revival here as it has in Europe and Asia. But we also need something that is smaller than a bus, but cheaper than a taxi, to get better penetration into suburban subdivisions. Much better use of existing technology for ride booking and sharing will be needed, but this is the only way to make suburban sprawl work without cheap gasoline and lots of cars.”

A Shift in Attitude

In our quest for relief to current urban problems the first shift may not be in the type of transport, but our ideas of what a city should be. And if we can do that, our experts say, we can conquer not only congestion, but perhaps sprawl, traveling time, and yes, even that sense of disassociation we have within our communities.

Schipper looks at the problem philosophically. “The point is the emphasis must shift from asphalt and parking lots to civilized places! The agora (in ancient Greece, the marketplace and gathering place) is wonderful. If people don’t care where they are as long as there is a Starbucks, that’s really sad.”

All our experts agree that the development of neighborhoods – real, fully functional neighborhoods where people live, work, play, and do much of their socializing within a comparatively small sphere – is essential.

Quality Urban Energy Systems of Tomorrow (QUEST), an Ottawa-based network of citizens from the energy industry, environmental groups, governments, academia and consulting communities, pulls no punches when it comes to the city of tomorrow. “For a community or city to be sustainable, we believe that increased densification and mixed-use neighborhoods will be needed. The current model with downtown office cores and suburban bedroom communities encourages increased transportation and consequently energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. The city of the future needs to be designed through an energy lens that addresses land use, waste management, water management, transportation, and energy use.”

New Urbanism: The Efficient City

New Urbanism: The Efficient City

The QUEST concept may be idealistic, yet its themes are common amongst those who look beyond old school urban principles and towards what has tritely become known as New Urbanism, essentially the promotion of walkable neighborhoods. Says Rees, “We can achieve much greater densities by permitting mixed uses, redeveloping low density areas and relying on walking, not driving. Huge amounts of land within cities are used ineffectively – or not at all. We just have to be much smarter about land use.”

The problem with idealism, of course, comes when putting those ideals into practice. And in that our experts agree once more – it’s going to be tough.

Rees references his current hometown of Vancouver, Canada. “In Greater Vancouver, a plan to develop regional town centers was developed, but not properly implemented as too many office parks were permitted. Fortunately, the regional out-of-town shopping malls that are now failing in large numbers can be retrofitted to become real urban places. Most large urban areas are polycentric – with a range of centers having their own hinterlands. Detroit failed because it relied on one industry, but also because it failed to become multicultural. Technology is much less important than attitudes – and policies.”

He concedes it’ll be a long process that certainly won’t be fulfilled within the decade between now and 2020. “Politicians generally lack vision, and people lack the opportunity to innovate. We need lots of experiments, which means failures as well as successes. If we do not risk failure we cannot learn. Most politicians are risk averse.”

Powering Home of the Future

Energy within our homes is another key concern, but one that seems somewhat less dire if we shift our urban planning focus toward the close-knit New Urbanism neighborhood model. Indeed, the QUEST concept seems to hinge on just that. According to the organization’s manifesto, “The QUEST vision builds on progress that has been made on energy-efficient appliances, eco-efficient buildings, district heating systems, renewable energy technologies, waste heat utilization, waste recycling and landfill gas capture, net zero energy homes, green roofs, and many more innovations that have paved the way for radical changes in the way quality energy services can be provided.”

The organization views integration as the biggest change, but sees a New Urbanism future where “individual homes and buildings will be connected to those around them, enabling them to take advantage of the excess energy produced.”

The Milk Man Model

And what of solar and wind power, both of which are seen by some as powerful new allies in the home of the future? Golden, clearly a believer in the potential of hydrogen as it applies to automobiles, is no less enthusiastic about its role in our homes. “Solar is incapable of producing more than a fraction of our power needs. The best way to be green is to have clean fuel delivered for onsite conversion in a fuel cell,” Golden says, a so-called Milk Man model. “You can have solar on your roof, but you’re fighting against square footage here. To be fully green, we need to have fuel delivered to homes and cities.”

Likewise, Rees sees wind and solar as being just a part of the urban energy solution. “Photovoltaic film (a technically superior method of harnessing the sun’s energy) could change that. But low-tech solar water heaters on roofs are common in Europe. Here codes often do not permit them. Geothermal has huge untapped potential. But simple energy efficiency gains like better insulation and windows have still to be implemented widely.”

The Year 2020: Just Scratching the Surface

In this series, we’ve tried to focus not on the distant future, but on the future that most of us will experience – that of the next decade. In Parts I and II, we did just that. Ultimately, though, the implementation of any real change to our cities, our neighborhoods, and the way we move amongst them will likely take much longer than that. This is a complex, highly fluid, sophisticated subject that involves modifications to so much of our everyday lives. We’ll be well on our way to something better and something far more sustainable by 2020, but we won’t yet have arrived. We hope you enjoy the journey.

Check out Part I and Part II in our series about life in the year 2020.