Researchers at the University of California San Diego have developed a tiny ultra-low power biosensor that’s designed to be injected into the body for continuous alcohol monitoring. Unlike the wearable alcohol monitors we’ve previously covered at Digital Trends, which let drinkers know if they’re over the legal alcohol limit on individual nights out, the UC San Diego device is intended to be used for long-term monitoring of patients in substance abuse treatment programs.

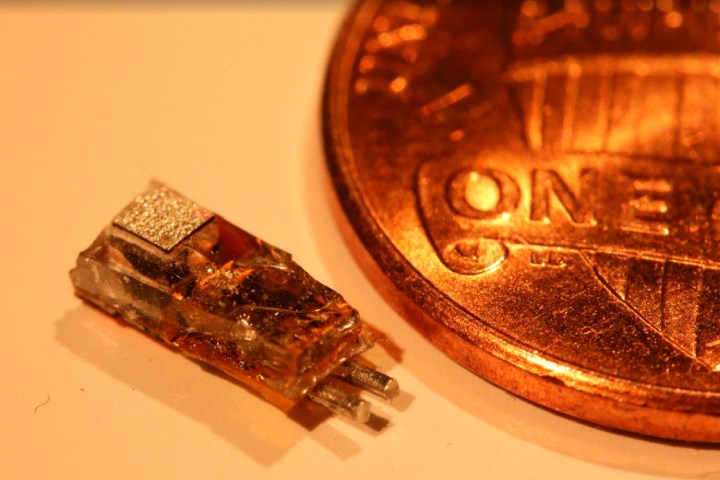

The biosensor chip measures only 1 cubic millimeter in size. It can be injected under the skin in interstitial fluid, the fluid which surrounds the body’s cells. It contains three sensors. The first is coated with alcohol oxidase, an enzyme that reacts with alcohol to generate a byproduct which can be detected electrochemically. The second measures background signals, while the third detects pH levels. These last two levels are then canceled out to make the alcohol reading more accurate.

The resulting number can then be read on an associated device such as a smartwatch. Communication between the chip and the smartwatch is carried out using radio signals. These are transmitted by the watch and then reflected back by the chip in a modified form, which reveals how much alcohol has been detected in the bloodstream.

One of the most impressive parts of the wearable device is just how little power it requires in order to work. It needs just 970 nanowatts to function, which is around 1 million times less power than a smartphone uses to make a phone call. This not only preserves battery life for the wearable, but also avoids the device generating too much heat inside the body.

So far, the researchers have tested the chip in a lab experiment in which it was implanted in diluted human serum underneath layers of pig skin. Next, the researchers hope to test the chip in live animals. The group is also working on additional versions of the chip which could monitor the presence of other drugs in the body.

“This is a proof-of-concept platform technology,” Drew Hall, the electrical engineering professor who led the project, said in a statement. “We’ve shown that this chip can work for alcohol, but we envision creating others that can detect different substances of abuse and injecting a customized cocktail of them into a patient to provide long-term, personalized medical monitoring.”