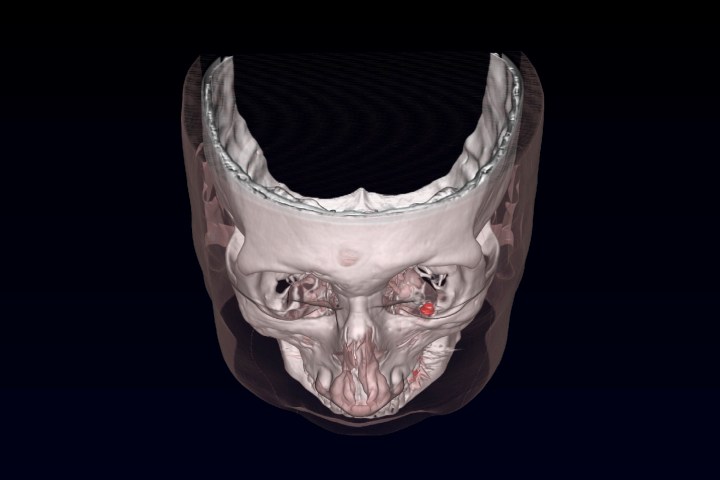

That’s the conclusion reached by researchers at the U.K.’s University College London and Oxford University, who have developed a new approach to dealing with the so-called “dancing eyes” syndrome, which affects around 1 in 400 people. This condition can be highly unpleasant for sufferers, making it appear like the world around them is constantly on the move. The newly developed procedure stabilizes the eyes through the implantation of titanium-encased magnets in the eye socket. Two magnets are used in the procedure, with one placed on the bone at the bottom of the eye socket, and a smaller one sutured to one of the muscles which controls eye movement.

“A neural problem is naturally felt to be in need of a neural solution,” Dr. Parashkev Nachev, a UCL neurologist and lead author of the paper, told Digital Trends. “Most approaches to treatment therefore focus on changing the way in which the underlying neural systems work.”

The issue with this is that solutions involving drugs can have the side effect of making patients unacceptably drowsy. The complexity of the disorder also means that what works for one patient may not work for another. Nachev likens it to expecting to deal with any motherboard faults in a computer simply by moving the power supply voltage up or down.

“We therefore took a different approach, focusing on the point where the neural systems converge: the muscles moving the eyes,” he said. “Since the forces involved in making saccades are usually far greater than those involved in nystagmus we can theoretically apply a counteracting force that damps the nystagmus but leaves saccades intact. This cannot be done directly, through a flexible stitch, for example, because the eye tends to respond to such restriction with scarring, resulting in a frozen eyeball, fixed in the head. Rather, we must deliver ‘action at a distance,’ applying a damping force without direct mechanical restriction. This is what our implant does.”

While Nachev noted that this treatment is still in its early days, it has already been successfully demonstrated on one intrepid patient in his late forties. A paper concerning the team’s study was recently published in the journal Ophthalmology.

Between this, devices that use magnetic fields to distribute drug doses, and other attractive implants, it seems magnetism is the hot new thing in medicine!