“If I told you right now to think about a cat doing a headstand on top of a soccer ball, you’re gonna think of that thing,” said Adam Haar Horowitz. “This is the same idea, except that in a state of semi-sleep, [it turns out that] you’re highly suggestible, and your thoughts are highly visual. If you say something to a person at that point, it’s highly likely that they are going to visualize that thing in their sleep, i.e. dream about it.”

Haar Horowitz, 27, is one member of the Dream Lab, a highly experimental lab-within-lab-within-a-lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that sits under Professor Pattie Maes’ Fluid Interfaces Group at MIT’s world-famous Media Lab. For years, the Media Lab has been home to some of the most unorthodox and inventive projects in tech, whether it’s a collapsible car able to park in just a third the space of a regular car or a computer vision system that can tell you safe an urban area is. Some of these ideas are never heard of again; others become the guitar-shaped controller from Guitar Hero or the Scratch programming language used by hundreds of millions of kids around the world. (Yes, both of those came out of the Media Lab.)

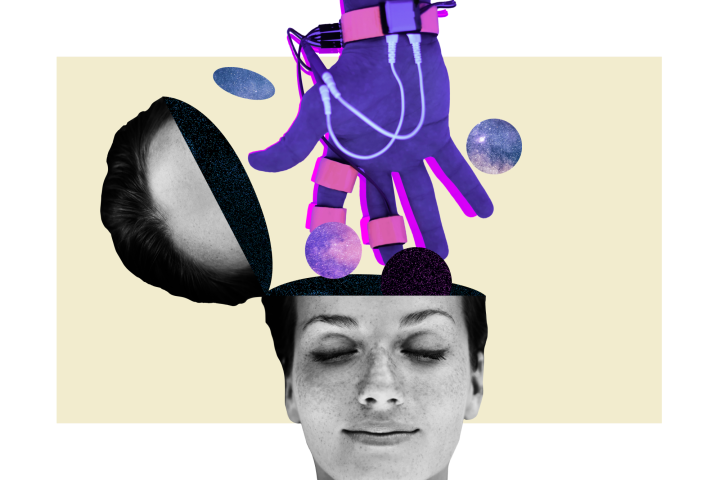

But even by the boundary-pushing limits of the Media Lab, the Dream Lab’s work is excitingly off-the-wall. What project leader Haar Horowitz and a team of colleagues — including researchers Ishaan Grover, Pedro Reynolds-Cuéllar, Tomás Vega, Oscar Rosello, Eyal Perry, Matthew Ha, Christina Chen, Abhi Jain, and Kathleen Esfahany — have built is a wearable device designed to hack your dreams. And, they hope, help change them for the better.

“Until now, sleep research was confined to labs with bulky equipment,” Eyal Perry, who helped build an accompanying iOS app for the so-called Dormio project, told Digital Trends. “The recent developments in the cost and availability of biosensors, as well as the rise of machine learning algorithms to analyze data streams, unlocks a new age where sleep study is done where people actually sleep: In their homes. Our brain is still the most fascinating piece of technology we hold, and projects like [this] could allow anyone to tap into the vast potential that lies within.”

Inception, but it’s real (well, kind of)

Here’s how Dormio works in a nutshell: The user wears a gloved device, a little bit like one of those old Nintendo Power Gloves from the 1980s, that collects biosignals which track changes in sleep stages. These signals are tracked via the hand using data related to a wearers’ finger muscle tone, heart rate, and skin conductance.

While we may not realize it, all of these are things that change when a person is asleep. When the biosignals appear to signal the end of a sleep transitional state, the device triggers an audio cue to be played, waking the user slightly, but not enough to jolt them back into a state of full wakefulness. This audio cue is, to liken it to the Chris Nolan movie such work immediately brings to mind, the “Inception protocol.” They enter the dreams as new content, making it possible to alter the course of a person’s dream. The system then quietens down until biosignals appear to signal another transition into a deeper sleep. Rinse and repeat.

The amazing thing — and, really, the important thing — is that it works. Like, well. As Haar Horowitz points out, some of this shouldn’t be so surprising. Researchers have known for some time that it’s possible to plant mental seeds that can dictate the contents of our dreams — like suggesting the idea of a cat doing a handstand on a soccer ball. But the way they were going about this was often frustratingly inexact.

“People have been trying to do dream control for such a long time,” Haar Horowitz told Digital Trends. “In neuroscience labs, there have been all these attempts at dream incubation and they just haven’t worked that well. In my opinion, it’s because they’d say to [participants], ‘OK, I want you to dream of dragons or dream up a solution to this algebraic problem’ and then they would send them to bed hours later, and wake them up hours after that and ask them what they had dreamt about.”

This is flawed, he said, because there are so many opportunities for forgetfulness or intervening thoughts to arise in the time between the instruction and sleep. Haar Horowitz’s idea was to wait until people are neurochemically in a sleep state and then “slip in a dream” at that point. “I’m just doing it all much more condensed,” he said.

In a study of 50 people, which became Haar Horowitz’s thesis, Dormio was used to incubate dreams relating to a tree in snoozing test subjects. Others slept without incubation or stayed awake. Afterward, the participants were tested on a range of tree-themed creativity tests, such as quickly thinking up creative uses for timber. The results suggest that Dormio can help guide dreams and augment waking creativity since participants who received sleeping incubation from Dormio experienced significantly higher tree-related dreams than other sleepers. They also performed better on the creativity tests than other study groups.

Too weird, too fluffy

When it comes to technology, we often tend to think of convergence as the mashing together of once-unrelated products or tools. The iPhone, as Steve Jobs famously told the world upon its introduction in 2007, was a phone, an iPod with touch interface, and a portable internet communication device. But this is only one way technological convergence happens.

Arguably the more exciting part, and perhaps the one that leads to the previous result, is the combining of researchers from different disciplines. Artificial intelligence, for instance, was driven forward by an assortment of investigators with very different interests. Some were psychologists interested in understanding how the human brain worked by reverse-engineering it. Others were engineers hoping to make more versatile computers.

Work like that carried out by MIT’s Dream Lab demonstrates another of these beautiful convergences. Dreams are, for many researchers, somewhat frightening — too associative, divergent, and metaphorical. Haar Horowitz said that they can be “a little too weird, a little too fluffy, a little too personal.” They are like trying to discuss the soul with a scientist focused exclusively on the brain.

“It always materializes as a story, and you have to sift through the stories to find the stimulant.”

“If you introduce the same stimuli of red flashing lights to five different people in their sleep, for one person it’s going to be the fire engine that they grew up with and for another person it’s going to be the red eyes on the wolf that they saw one night,” he said. “It always materializes as a story, and you have to sift through the stories to find the stimulant.”

By dint of its multidisciplinary nature, those who thrive in the Dream Lab have interests that don’t cleanly channel down one avenue, whether that be neuroscientist, engineering, or whatever else. They might be too much of an engineer to be a pure neuroscientist, and too interested in things esoteric to be a pure engineer.

Haar Horowitz, whose family counts playwrights and brain scientists among its ranks, epitomizes this divide. He’s fascinated by science, but equally happy to talk about Freudian dream interpretations. He has certainly never been afraid to explore more alternative paths in life. When we spoke with him via Skype for this article, he was quarantined in a commune in Mendocino County in California. (“Feel free to call me whenever tomorrow,” he wrote in one email. “I’m just helping paint my friend’s house and shear her sheep.”)

This unique convergence of influences is the world the Dormio projects comes from — and why it could help revolutionize work in all the disciplines it touches upon. “I’m inspired by these links that have happened, and can still happen, between something like a spiritual counterculture and something like a kind of edge, punky tech that says, ‘I’m cool with the weird stuff. I’m gonna grab it, make it useful, and put it out in the world,’” Haar Horowitz said.

Mysterious biological machines

“The brain is a beautiful, complicated, and mysterious biological machine,” said Tomás Vega, a researcher who worked on the project, now running a startup making invisible interfaces for hands-free human-computer interaction. “The more we learn about how it works, the better we understand its potential. This knowledge can allow us to develop interfaces to hack our own selves and extend our abilities beyond what we thought possible. To become better.”

Vega, like Haar Horowitz, was previously in the Fluid Interfaces Group of the Media Lab. Haar told him about the idea and Vega became interested. For an assignment in the “How To Make (Almost) Anything” class, Vega built the first Dormio device; designing, milling, soldering, and programming the first version within one week. The resulting prototype could sense heart rate, electrodermal activity and hand flexion, before transmitting this data via Bluetooth to an app which he also built. This web app displayed the data from Dormio the data in real time. He called it OpenSleep, a platform for sleep hacking and research.

Vega notes that the inventors of a new technology are rarely the best judges when it comes to how it can be used. They also frequently have limited control over how it will end up being utilized. But he believes that it could be used to improve people’s lives.

That might be helping to carry out nightmare therapy, potentially making this a valuable tool for fighting the devastating effects of PTSD. By helping users to reappraise traumatic experiences, Dormio could aid with healing people. It could additionally be useful for augmenting memory consolidation for accelerated learning. Or to assist people with better “seeing” themselves through what Haar Horowitz calls “introspective windows.” As his thesis showed, it could also help make people more creative; directing dreams in a way that yields hyper-creative sleep states for idea generation. Or, heck, it could just to prompt you to relive a particularly enjoyable dream for reasons of calming mood optimization.

All of these, to some degree, are ways in which researchers are already using the Dormio tool built by the Dream Lab. Perhaps appropriately, just like the abstract imagery in a dream, the way this technology will be utilized is best left open to interpretation.

But Vega said more work needs to be done. “I think the biggest challenge is yet to be faced,” he said. “We do not fully understand the long-term implications of intervening in our natural sleep cycle in these ways … we ought to be careful.”

A dream you can build for $40

Whatever form or use-case Dormio finally takes, there’s no doubt that sleep — and, specifically, dreaming — is powerful stuff. It has far more of an impact on our waking selves than we might imagine. During the day, we’re solving basic problems in order to stay alive. But at night is when our brain really goes to work. At that point, we’ve maxed out our hippocampal storage, the part of the brain that deals with short-term memory. It’s then up to the brain to sort through the previous day, select what’s most important, and convert that short-term storage into long-term memory. It’s when we most readily draw associations that help us to learn and formulate ideas. It is, importantly, when we are the most susceptible to change.

“You can see yourself and think in ways in which you couldn’t think while you’re awake.”

“Sleep is this natural and organic way that we all enter into states which are low anxiety, highly fluid or highly associative, where we can access memories which are not accessible to us in the day and solve problems which we couldn’t solve during the day,” Haar Horowitz said. “In sleep, you enter into these different brain states. You can see yourself and think in ways in which you couldn’t think while you’re awake.”

Dormio won’t be coming to a Kickstarter near you. Nor will it become the flagship device of a new device maker with Haar Horowitz as its CEO. “I don’t want to be a business person,” he said. “I’m trying to figure out a way to make it accessible to people who don’t know anything about tech and don’t want to pay me any money,” Haar said. But he believes unflinchingly in the manta of the MIT Media Lab, which is not necessarily to commercialize, but to deploy. “[You want to] get that thing out there,” he said. “However you can get it out.”

If you want to build your own Dormio you can, courtesy of these open-source instructions, circuit board design, and the necessary biosignal tracking software on Github. In the future, the team wants to make it even more widely accessible — and even cheaper than its current approximate $40 build cost. (You can also sign up to participate in future experiments.)

“We spend a third of our lives asleep and dreaming, yet so many of us forget what went through our minds upon waking,” Christina Chen, another researcher who worked on the project, told Digital Trends. “Giving people the opportunity to connect with themselves even when asleep, to be creative with the prompts, to be entertained or edified or surprised by the results, and the chance to take dreaming with them into their waking life — that might not be transformative in an earth-shaking way. But [it] still can change people’s lives and their relationship to sleep and dreams for the better.”