The NBA reached a record 240 million more fans on social media this past year than it did last season. But getting them to really feel the game through Facebook isn’t realistic. A video recap of last night’s game, a live chat with NBA players, and all the Vines in the world don’t create the same visceral experience you get from a court-side seat, watching Steph Curry hoist up a three-pointer and stare at you before the shot even swishes through the net.

“How do the technology and the devices catch up with consumers?”

The NBA is well aware that such an experience is not only rare but impossible for the millions of its fans that do not live near an arena, or can’t afford a court-side seat with the stars. VR could help, right?

Not so fast.

“I think there’s — and I’m being hyperbolic — five people who have the devices,” said Melissa Rosenthal, Senior Vice President of Digital Media at the NBA, explaining the Association’s tepid enthusiasm with virtual reality and how VR fundamentally does not fit with the game of basketball yet. “We’re hoping as the price point comes down and there’s more of a commercial opportunity, there will be more of a consumer adoption and a bigger opportunity there,” she added.

During a recent meeting with Digital Trends at the NBA’s headquarters in New York City, Rosenthal explained the agency’s dilemma: When do you get started with a nascent technology? “How do the technology and the devices catch up with consumers?” she asked.

Testing the VR waters

Beside Google Cardboard and Samsung Gear VR, consumer-grade virtual reality headsets are not exactly flooding the market. Back in February, the Samsung Gear VR’s limited public adoption was a reason the NBA began working with Samsung on virtual reality content. That lack of exposure was ideal for testing a new product, said Jeff Marsilio, the league’s vice president of global media distribution, in an interview from February.

The experience was frustratingly novel. Watching the 2015 NBA All Star players enter with a VR helmet strapped to your head was impressive, until you looked back and saw pixelated fans with the same cheers and flat expressions throughout. Standing at the top of the three-point key in an empty gym, with LA Clippers’ shooting guard J.J. Reddick circling you while shooting three-pointers and narrating his technique, should be amazing. Instead, it felt more agonizing than an immersive instruction, being part of something so real but not at all part of it.

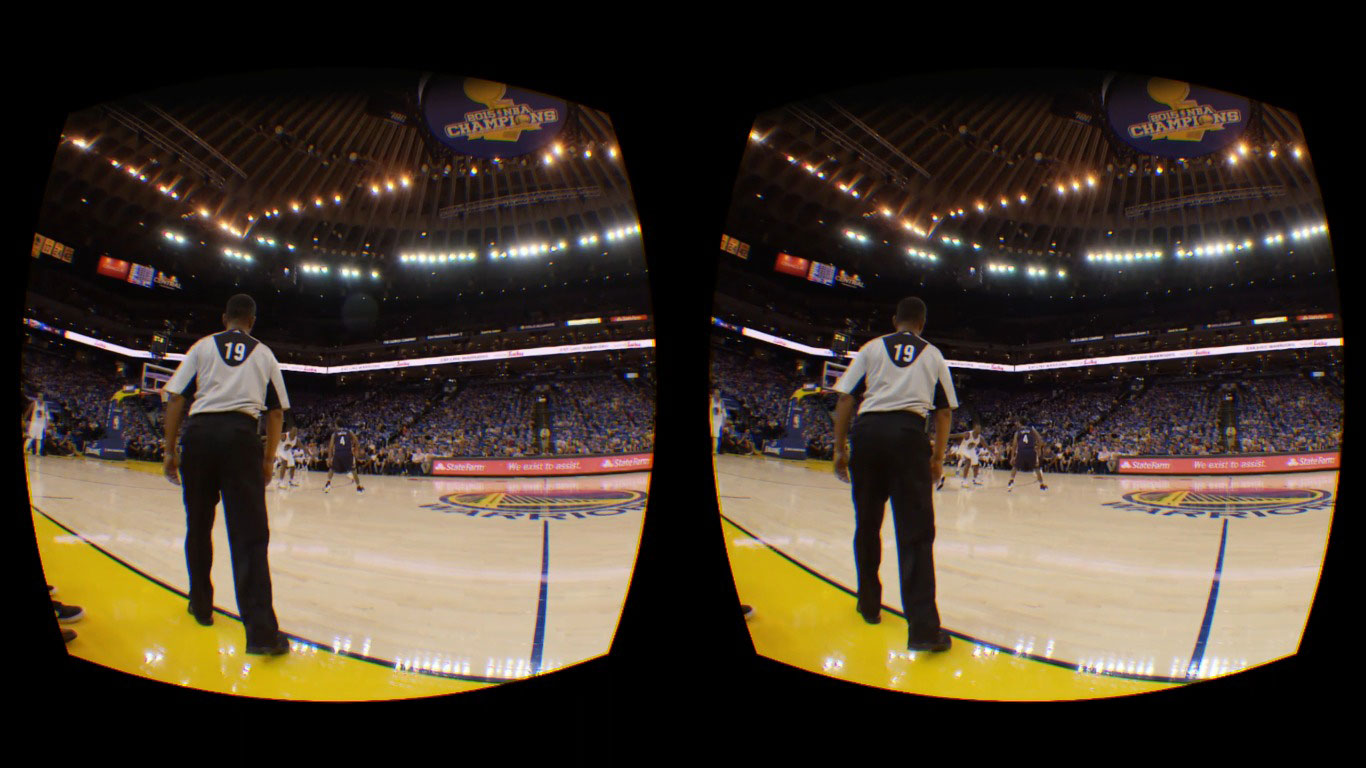

In October, the NBA, Turner Sports, and virtual reality company NextVR live streamed the Golden State Warriors vs. New Orleans Pelicans opening day matchup. It was the first NBA game live streamed in virtual reality, with the sound of sneaker soles screeching across the crisp shine of the hardwood floor. It gave the most hope for what VR and the NBA’s marriage could bring: a unique recreation of normally unavailable views.

Virtual Reality today

A little over nine months after the NBA’s experiment began, virtual reality’s limited reach has lost its charm.

It’s not just the lack of adoption needed for a global entity such as the NBA to reach a significant portion of its fan base; virtual reality and the NBA seem to be fundamentally incompatible. “When you put the device on, you’re so disconnected from everything else around you and so much about the game is that communal experience,” Rosenthal told Digital Trends. Telling a sports fan to sit stationary and enjoy a game at the Staples Center — in a space that seems like they’re with fellow sports fans, until the technology’s limitations remind them they’re actually alone — is at best enjoyably counterintuitive. At worst, it’s a cruel mirage of future not yet realized.

“If we’re a global sport we’re going to train kids, not just athletes, but kids around the world to shoot a three-pointer like Steph Curry.”

Rosenthal admits that “a lot of the physicality of VR right now is a bit isolating,” but said some companies are working on including “social tentacles” where people can communicate in virtual reality via avatars.

The NBA’s hesitation is not indicative of disinterest in the slightest bit. Maybe recreating a live game atmosphere, where you’re ensconced by screaming fans from every vantage point, is a ways off. But what about practices? Rosenthal believes virtual reality can also be a “game changer” in the sport of basketball through teaching children across the world how to play the game.

“Obviously, if we’re a global sport we’re going to train kids, not just athletes, but kids around the world to shoot a three-pointer like Steph Curry and kind of be in that VR experience where you’re next to him is amazing,” Rosenthal said with a visible grin on her face.

Rosenthal also mentioned the possibility of fans seeing a game from a player’s perspective as a possibility and that is when you realize the NBA are like kids in a candy store with virtual reality. It’s just, these kids want to make sure they’re not sacrificing a future of stomach aches for the prospect of momentary elation. Game on.