The search for life in outer space is like the holy grail of astronomy. But with some 170 billion galaxies in the observable universe, where do we even begin?

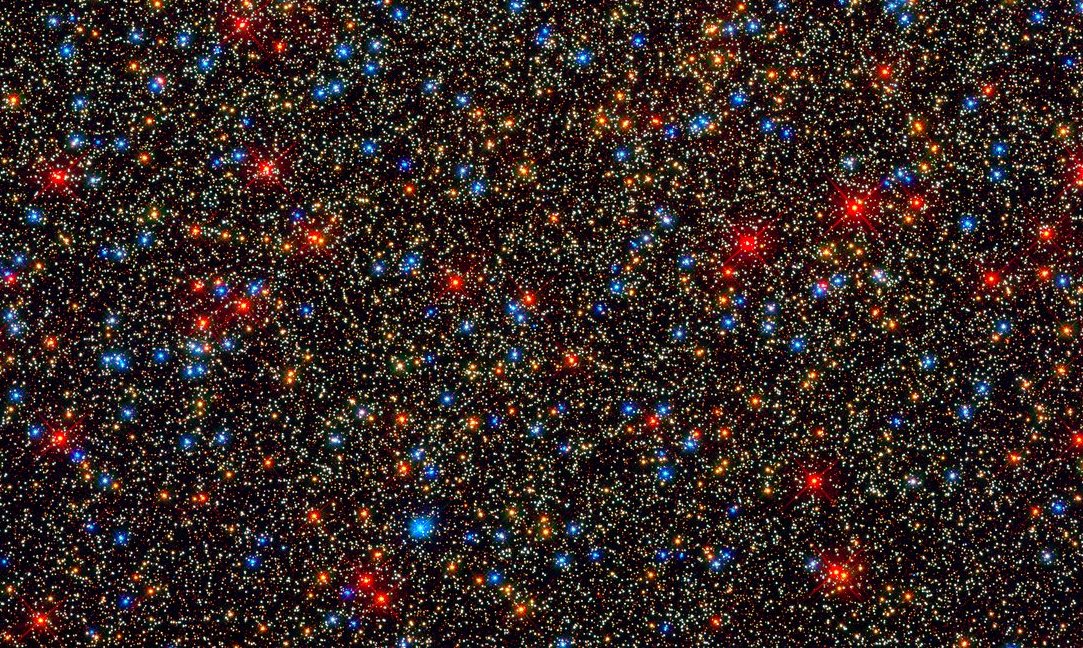

How about with the bright, Christmas lights-like stars of the densely packed globular cluster Omega Centauri? Surely something so spectacular could harbor life.

Not so. According to a paper published this month in The Astrophysical Journal, scientists can safely cross it off their list.

Omega Centauri is a sight to behold. It contains some 10 million stars, making it the largest globular cluster in the Milky Way. And at about 16,000 light years away, the globular cluster is visible to the naked eye and a prime object of observation for professional astronomers. So it makes sense that scientists would home in on Omega Centauri in their hunt for extraterrestrial life.

“In the search for planets around other stars, we are investigating a wide range of stellar environments that are very different from our own system,” Stephen Kane, a professor of planetary astrophysics at the University of California, Riverside, and study lead, told Digital Trends. “In particular, we are looking for planets that lie in the habitable zone where water on the surface of the planet could be in a liquid state, something which is necessary for life on Earth. The results of our study show that it is highly unlikely that the stars in the largest globular cluster to the Milky Way, Omega Centauri, can host a planet in the habitable zone.”

Kane and his colleagues looked at roughly 500,000 stars whose age and temperature could potentially support planets with life. They measured the temperature and brightness using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and calculated how often these neighboring stars would pass directly within each other’s habitable zones.

“The results of our study show that, on average, the stars of the cluster will pass directly through the habitable zone of other stars around once every million years,” Kane said. “This means that for most of the stars, it will be impossible for a planet to remain in the habitable zone of its host star, thus removing the planet from a location where it could maintain a long period of energy and climate stability.”

Kane said it could be possible for Omega Centauri to contain a group of small planetary systems near its core (much like TRAPPIST-1, a promising solar system for harboring life) but that their calculations made the existence of such systems unlikely.

Moving forward, Kane and his colleagues will collect more Hubble data about our neighboring clusters to determine stars’ habitable zones and how often they cross each other’s paths.