At the heart of our galaxy lies a sleeping giant: A supermassive black hole which is 4 million times the mass of our sun. It’s believed that most other galaxies have such an enormous black hole at their center, too. But now, astronomers have discovered something unexpected about these monstrous black holes. It may be possible for planets to orbit around them.

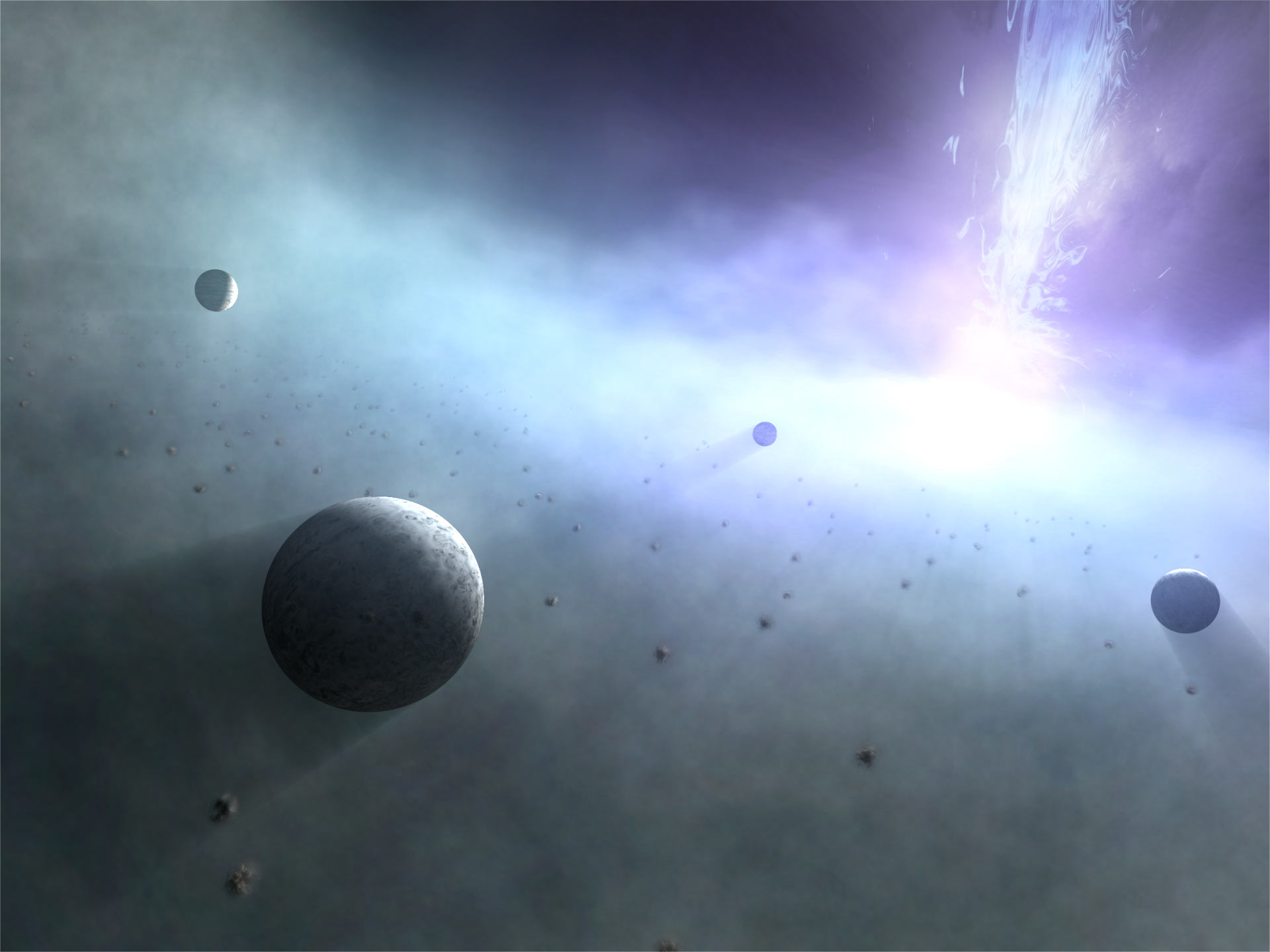

It was generally thought that planets only formed from protoplanetary disks of dense dust and gas which are found around stars. The new research from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan suggests that planets could also form in the doughnut-shaped cloud of dust and gas, called a torus, which is found around a supermassive black hole.

“A torus can contain as much as a hundred thousand times the mass of the sun[‘s] worth of dust. This is a billion times the dust mass of a protoplanetary disk,” Professor Eiichiro Kokubo from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan and colleagues said in a statement.

For this dust to form planets, it would need to first form clumps, which requires areas within the cloud to have different temperatures. “A dust disk around a black hole is so dense that the intense radiation from the central region is blocked and low-temperature regions are formed,” the authors explained. This dust could come together to form proto-planets when the temperature is low enough: “In a low temperature region of a protoplanetary disk, dust grains with ice mantles stick together and evolve into fluffy aggregates.”

The researchers showed that these low temperature regions could give rise to small icy dust particles, which could eventually grow into Earth-sized planets. “Our calculations show that tens of thousands of planets with 10 times the mass of the Earth could be formed around 10 light-years from a black hole,” Professor Kokubo said in the statement. “Around black holes there might exist planetary systems of astonishing scale.”

This surprising finding is challenging the way that we think about planetary formation. “With the right conditions, planets could be formed even in harsh environments, such as around a black hole,” Professor Keiichi Wada, from Hokkaido Universities, said in the statement.

The findings are available to view on pre-publication archive arXiv.org and will be published in the Astrophysical Journal.