The Internet of Things, or IoT as it’s commonly referred to, has been widely heralded as the biggest thing to happen to enterprise, manufacturing, and yes, even the humble family home. That’s because when “things” can talk to one another automatically — without the intervention of us dumb humans — magic happens.

When the things use Wi-Fi or Bluetooth — or protocols like Z-Wave and ZigBee — to chat amongst themselves, there’s no cost to this communication. But when mobile networks like 4G or LTE are needed, it’s a much more expensive proposition. For IoT devices that don’t have fixed installations, e.g. a dashcam in a car, there’s no other option: Customers will have to pay a carrier for the data transmission. For a specific class of IoT device however, that is about to change, big time.

IoT devices running on 4G or LTE is like hitting a mosquito with a sledgehammer.

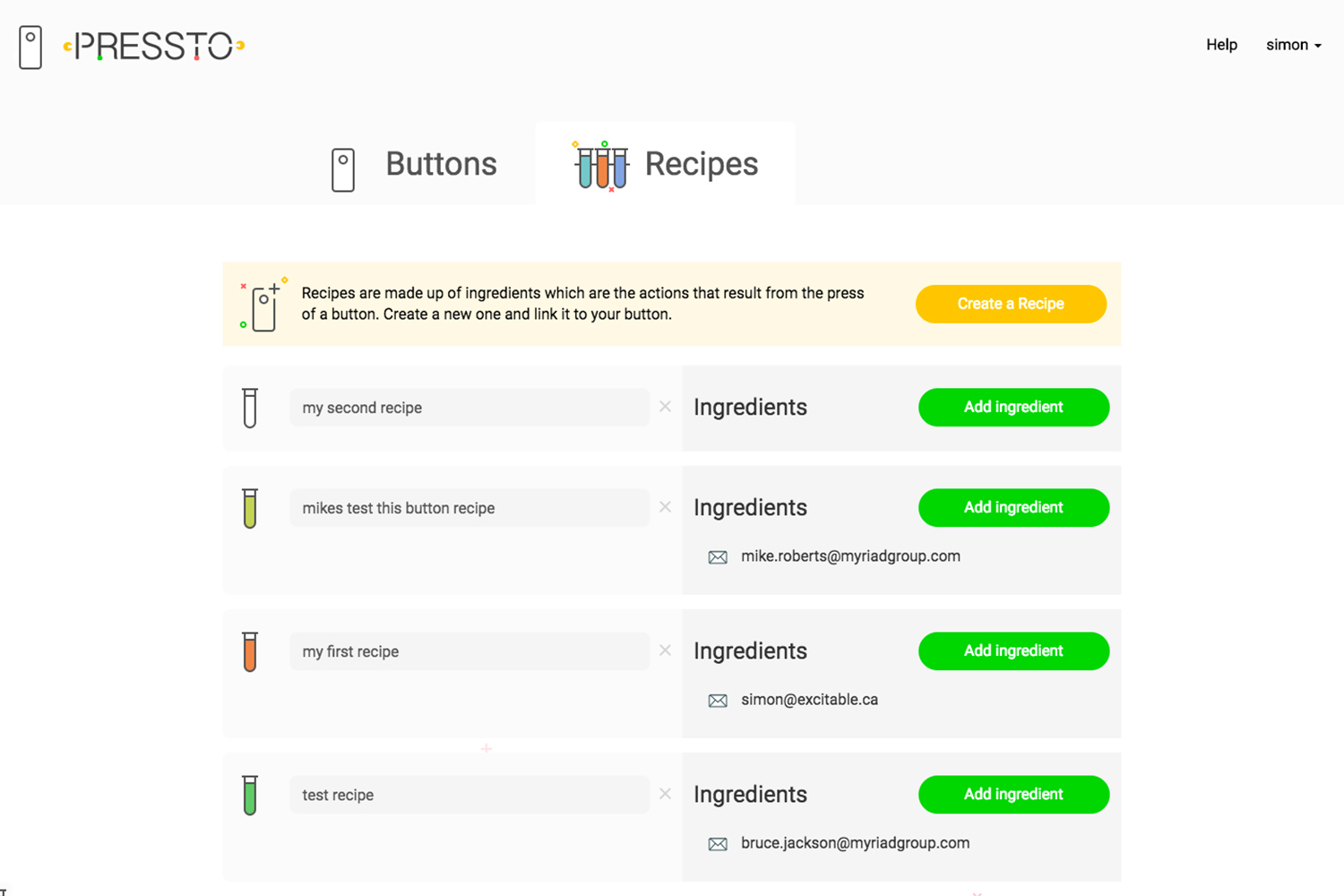

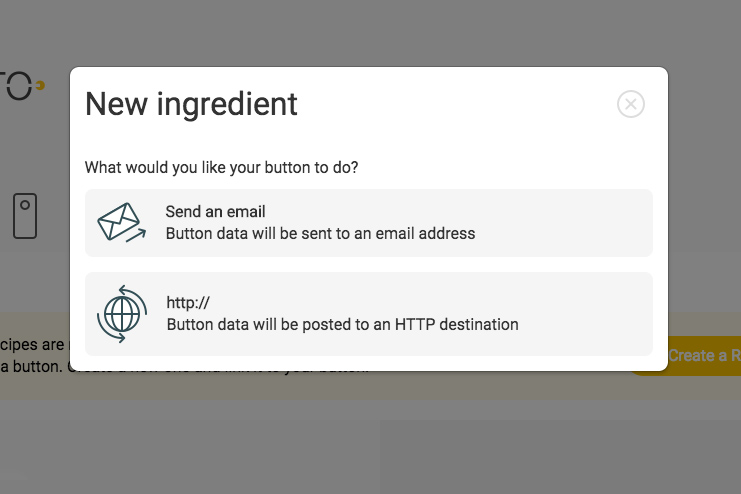

Enter Pressto, a £40 (about $49 US) Amazon Dash lookalike, created by Swiss-based Myriad Group, a company whose roots in wireless telecom go back to 2001. Don’t let the Pressto’s similarity to Amazon’s one-click product ordering gimmick fool you: You can configure what the Pressto does using an online dashboard. Button presses initiate recipes, which at the moment are pretty basic. Recipes can send emails or post data to a server. The emails can contain a maximum of three types of data: A map showing the button’s location, today’s weather forecast, and the raw data generated by the button in JSON format.

If you’re yawning right about now, stay with us. The Pressto is actually a proof-of-concept device built on Myriad’s IoT platform, ThingStream.io, and uses the little-known Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) protocol to send short, 182-character messages to the Pressto server, across cellular networks.

Here’s the kicker: Not only can the Pressto send an unlimited amount of these short messages for free, the device works anywhere in the world that has a GSM network, costs very little to build from off-the-shelf components, consumes hardly any power, requires no carrier accounts or contracts, and there are no roaming charges. In fact, the only ongoing charge for using a Pressto is $5 a year. Even Amazon’s IoT version of the Dash can’t make that claim.

Put simply, Pressto just became the only device that can communicate with the internet, from anywhere, without the need of a paid carrier relationship, over existing GSM cellular networks.

Myriad CMO, Bruce Jackson explains why the Pressto and its use of USSD changes everything. “A lot of people think of IoT services like Google Home or Alexa that are pretty rich, heavy-bandwidth applications,” he told Digital Trends. “But if you look at the whole spectrum of things you might like to do, there are loads of things that require relatively small amounts of data to be sent.” This is where Myriad’s repurposing of the USSD protocol comes into play. “USSD is a really good bearer for taking that kind of data,” Jackson said, and the evidence does seem overwhelming. Here’s a quick snapshot of what USSD can do. Think of USSD as a network engineer’s version of SMS. It has the same constraints on payload (182 characters per message), but with some awesome extra perks.

USSD messages are point-to-point. They originate with the sending device (in this case the Pressto button) and terminate at the destination (in this case, the Pressto servers). SMS messages make a stop along the way at your carrier’s SMSC (Short Message Service Center), where a copy of the message will reside for zero to four days, depending on the carrier. If you’re roaming, the number of copies increases with the number of carriers involved in getting the SMS message back to your home network. For privacy, USSD is much better.

Just like HTTP, USSD uses sessions. Once a device initiates a session with another device, that session will remain open until either the sender or receiver closes the session. In developing countries, the session-based nature of USSD is used for Facebook access on feature phones, via a menu system.

USSD is fast, with a latency that can be measured in milliseconds in some cases.

It’s low-power. The Pressto’s built-in rechargeable 800mAh battery is good for about six months between charges, even if the button is pressed several times an hour.

It’s free. While there are a few smaller carriers who charge for USSD messages, as a rule, most don’t. It’s legacy as a protocol used at the core of a network, rather than a subscriber-facing function like SMS, keeps it from being treated as a chargeable service.

Is there any other way to do the same thing?

The full implications of the Pressto button and ThingStream.io — the IoT platform built by Myriad that powers it — don’t become apparent until you consider the current state of the mobile connectivity marketplace.

Until now, if you wanted to create an IoT device that could communicate from anywhere, you’d need to create a relationship with a carrier that included roaming, acquire the necessary SIM cards, and then keep an eye on your business model to make sure the cost of communication didn’t outweigh the benefits. This can get so expensive, businesses have already gone to some unusual lengths to control it.

A device that has no internet connection of its own is able to communicate with a remote server for free.

“You would be amazed at the number of IoT devices in North America that are being done with SIM cards from European operators,” Jackson said, pointing out a reality in the current carrier environment: It’s often cheaper to buy data from overseas carriers and take the additional hit of roaming charges, than it is to buy data domestically.

For bandwidth-intense applications like voice or video, these carrier agreements still make sense. But when it comes to the low-bandwidth, low-power communications needed to run the millions of IoT devices that are now pouring into the market — like industrial sensors or switches — they can feel like overkill. These devices don’t need 4G or LTE — even the aging 3G standard is like hitting a mosquito with a sledgehammer — but where can you turn?

“People are looking at LoRa and Sigfox because there’s no great solution for it,” Jackson said. He’s referring to two new platforms, France’s SigFox, and LoRa, an alliance that wants to standardize “carrier-grade IoT communication,” both of which are slowly rolling out low-bandwidth alternatives to traditional carriers. Neither SigFox nor LoRa have anywhere near the size of the existing GSM network footprint, they both require investments on the network and client sides, and naturally there are charges to use them, even if these charges are more proportional to the data used than with GSM carriers.

Aaron Allsbrook, CTO of ClearBlade, lamented this situation recently, pointing to the challenge of connecting simple devices like lights and temperature sensors to the internet. “A lot of people think it’s difficult because of carriers, contracts, data charges, and because of roaming,” Jackson said. “We want to demonstrate that for a lot of applications that’s not true. We’ve built [Pressto] as a technology demonstration platform to show people it works.”

Can’t anyone do this?

Well, no, not exactly. Because USSD is a core GSM network technology, you’d need a carrier to let you link your USSD gateway servers via VPN to their core network architecture. Jackson claims that this is no small imposition and that’s it’s only by virtue of Myriad’s long-standing relationship with its partner carrier that it was able to do this. “For all intents and purposes, we are our own network operator,” he said.

Our biggest question to Jackson was just how Pressto could essentially use carriers’ networks without charges, especially if they sensed there was potential money to be made. After all, these are the companies that in the past charged 50 cents or more just for a SMS message, and many still do when one of these SMS messages is sent to a phone in another country.

His answer was based partly on reality and partly on wishful thinking. “This is a line of business that carriers aren’t that keen to look at,” he said. “I think they’re after something different.” He reasons that carriers have spent so much money rolling out LTE that they’ll be exclusively focused on monetizing the apps that make use of that technology’s high-bandwidth capacity. Jackson also points out that carriers’ tendency to charge for equally low-bandwidth items like SMS messages had to do with perceived value to customers, not the cost of delivery. Since USSD has an even lower impact on networks than SMS, “We would have to be amazingly successful to even register as something that anyone would take any notice of,” he said.

So how does it work?

It took a few tries, but eventually Jackson was able to furnish us with a prototype Pressto button that does exactly what it promises. After quickly setting up an email-based recipe, a press of the button produced two green flashes of the tiny LED, and two corresponding beeps. Then about 10 seconds of silence, followed by a series of three beeps and flashes. A few moments later, the email arrived.

That’s not exactly the millisecond response time we were expecting, but Jackson explains that there’s a lot going on between the button press and the email being sent. Pressto uses no power whatsoever while it’s waiting for you to press its button. When you do, it has to wake up, find and sync with the nearest cell tower, send and confirm its USSD package, and then shut itself down once more. The actual USSD transmission is very quick, but it’s bookended by some much slower processes.

None of this detracts from the fact that a device that has no internet connection of its own via Wi-Fi, ZigBee, Bluetooth, or smoke signals, was nonetheless able to communicate with remote server for free, and nearly in real-time.

What’s next?

Needless to say, Myriad hopes that Pressto will be the catalyst for an entire ecosystem of low-power IoT devices that use its ThingStream.io interface. Jackson pointed out that even though the current recipes and ingredients available to Pressto owners are limited, Myriad plans to create links to automation services like IFTTT. In fact, with the existing email functionality, IFTTT can already be used with Pressto as a trigger, even if it’s not a direct link.

During our interview with Jackson, a number of possible consumer applications immediately came to mind. The first was asset tracking. At the moment, tracking tags use one or more of Bluetooth, GPS, Wi-Fi, or cellular data for communicating their whereabouts. While Bluetooth and Wi-Fi are free, their range and power demands severely limit their utility.

One application would be a panic button that works globally, doesn’t require a phone, and is instant and free to use.

Those that use cell towers for triangulation are better for power consumption, but still require data contracts with carriers to pass the information back to the user, resulting in annual fees. With what Jackson describes as a “relatively straightforward engineering change,” these trackers could use the Pressto’s USSD messaging service to drastically reduce costs.

Another application would be a panic button/locator that works globally, doesn’t require a connected phone, is instant and free to use. If the price is right, it could a be no-brainer for everyone from parents to backpackers, to search and rescue operations.

There’s even a chance it could be used to power the next generation of smartwatches. Taking a page from a now-defunct product, Microsoft’s MSN Direct collaboration with Fossil, could succeed in a world where no true killer app for smartwatches has emerged other than fitness and notifications.

The big money however, will be in the industrial IoT. Everything from pipeline monitoring to weather stations are potential use-case scenarios, and as the global GSM footprint increases, so too will the opportunities for ThingStream.io.