Lawton wasn’t about to take her diagnosis lying down. She connected with other sufferers online, engaging in video calls to hear about their experiences, and soak up any advice. She recorded her own observations in a journal, which would eventually be published as Dropping the P Bomb.

“Initially, I wrote it down for me,” Lawton told me when we spoke on the phone last month. “It was never meant to be a book; it was for me.” She had seen her father pen his own book when he started to deal with issues related to his sight. “When the going gets tough, you write it down,” she added.

Dropping the P Bomb was crowdfunded on Kickstarter, and as a result found its way into the hands of fellow sufferers, their relatives, and scores of people who never understood the first-hand experience of dealing with Parkinson’s disease. Just as her video calls helped her get to grips with her condition, Lawton provided a helping hand for people who were newly diagnosed — connections that wouldn’t have been possible without the internet.

My life is as normal as it can be, because of technology.

“It’s little things like that, all the way through to what’s happening now,” she replied, when we asked her how tech improved her life. “My life is as normal as it can be, because of technology. It’s not limited by Parkinson’s, it’s not limited by being in the same country as people, it’s not limited by what I can do physically.”

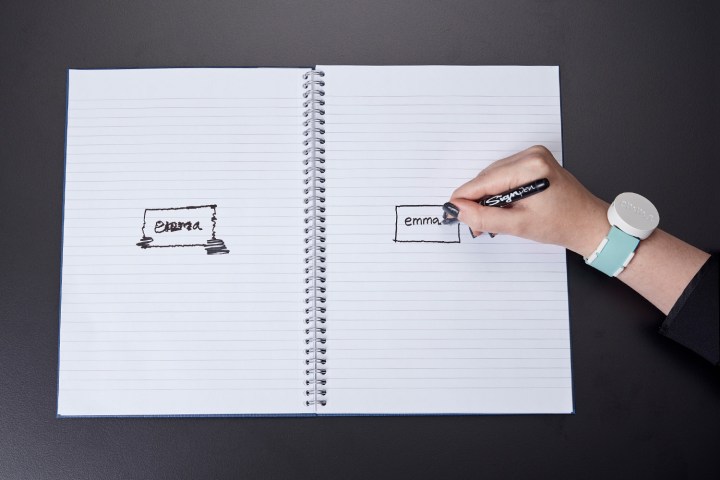

Last month, Lawton appeared on stage at Build 2017, in a segment dedicated to Project Emma, a device designed by Microsoft Research’s Haiyan Zhang to help her manage the condition. “It was an amazing experience — I didn’t really know what to expect, having never been to Build before,” she told Digital Trends. “We got a great response from people who wanted to collaborate.”

Project Emma counteracts the effects of Lawton’s tremor, allowing her to draw and write again. It’s a custom, one-off device, but Zhang is spearheading a research project that could help Parkinson’s sufferers on a much broader scale, with Lawton serving as a consultant.

“If anyone could help me, this woman could,” Lawton said when asked about her relationship with Zhang. “I knew she was bright from the start, but over time I’ve developed a more personal bond. We’ve forged ourselves into a weird partnership for life. We don’t know where it’ll take us.”

In addition to her role in Zhang’s research project, she’s a devices, apps, and gadgets strategists for Parkinson’s UK. Lawton is committed to using technology to help other people deal with Parkinson’s disease. And she’s not alone.

Meet the smart fork

Project Emma was designed for a BBC television show called The Big Life Fix, with the intention of remedying Lawton’s issues with drawing and writing. However, most people with Parkinson’s aren’t graphic designers. For them, being able to use cutlery is more helpful than being able to wield a pen.

When Anupam Pathak completed his PhD in mechanical engineering, he started to wonder how stabilizing technologies could help people who were affected by movement disorders. Eight years later, Liftware, the company he founded to pursue this idea, is thriving, and its products are helping sufferers across the United States.

“I remember first showing up with a plastic picnic spoon attached to a circuit board and motors that hardly worked,” Pathak told Digital Trends last month via email. “People were incredibly supportive, though, and were always eager to try my latest iteration, which often included changes to the firmware, exterior design, materials, and mechanical system.”

Liftware offers cutlery that’s purpose-built for users who can’t use standard utensils. The company’s debut product, Liftware Steady, uses motion stabilization technology to counteract mild to moderate tremor, which can be caused by conditions like Parkinson’s or essential tremor. It’s recently expanded its product line with Liftware Level, cutlery that counters the more extreme hand twists and rotations commonly associated with cerebral palsy, Huntington’s disease, and the aftereffects of a stroke.

“Our system works by measuring movements in an inertial frame (absolute motion), detecting whether these movements were due to hand tremor, and then correcting the disturbance by producing an equal and opposite movement,” Pathak wrote. “So, if the user’s hand shakes to the left, the device will move the spoon to the right an equal amount so that the spoon isn’t actually moving. The system makes these corrections thousands of times per second.”

The basic concepts that allow Liftware to counteract tremor were once used to stabilize gun barrels in tanks.

According to Pathak, the technology needed to affordably build Liftware wasn’t available until very recently. He and his team adapted commoditized inertial sensors and microcontrollers that were originally designed for use in the smartphone industry, to perfect their utensils. The basic concepts that allow Liftware to counteract tremor were once used to stabilize gun barrels in tanks.

Liftware was once an independent startup, but a few years back, the company was acquired by Verily Life Sciences, a research subsidiary of Google’s parent company Alphabet — and Pathak’s work has benefited greatly from the new arrangement.

“We were excited to join Verily in 2014, because it allowed us to scale our design and manufacturing processes so we could bring Liftware to more people who could benefit from this technology,” he explained. “The talent within Verily, and specifically within the hardware engineering team, has been invaluable in supporting new designs and improved sensors within our devices.”

Having Verily’s weight behind Liftware has allowed the company to go from strength to strength, to the benefit of people who need this technology in their everyday lives. “It is so meaningful to me when we receive positive responses from users who feel more confident when eating, or are more comfortable sharing a meal in public, or at the holidays,” said Pathak. “Our users have sent us heartfelt thank-you notes and cards which are proudly displayed on a wall in our office.”

Walking in another’s shoes

A blossoming field of research dubbed tele-empathy adds another dimension to the way medical professionals diagnose Parkinson’s, and helps relatives and loved ones understand how it affects day to day life.

Yan Fossat took the long road to his current role as head of the innovation lab at Klick. He studied mathematics, physics, and biochemistry, and spent some time working in graphic design and architectural CAD. He then went on to produce 3D animations and software in the medical industry. However, throughout his career, his work had two constants: technology and medicine.

“Because through my career I spent a lot of time with physicians, of various specialties, I think I have a fairly good idea of what their job is like,” Fossat told Digital Trends. “So it helps me design something that’s not just a fantastic idea in the boardroom, but actually would be useful in the real world.”

Fossat’s work in tele-empathy began as a project commissioned by a client that wanted its healthcare representatives to better understand the conditions customers were suffering from. The project never went ahead, but he was fascinated by the idea.

“The problem was very interesting,” he remembered. “We thought about it because the research in the lab at the time was very much on the digitization of medical symptoms. The idea of treating a disease as a function, as a mathematical function, that disrupts physiology. So, we sort of went ahead with it and said, ‘Hey, what if we digitized the tremors?’ Not the shake of the tremors, but what if we digitized the muscle activity.”

The result is SymPulse, a device that captures the muscle spasms that cause tremor in someone with Parkinson’s disease, and transmits them to a non-sufferer. Existing devices simulate tremor, but they serve as only a general simulation, and take the form of a large plastic glove with motors to shake your hand. SymPulse provides a more intimate window into the effect the condition has on a specific individual’s life.

“It’s giving you tremor, the fact that the hand is shaking is almost a consequence of that,” Fossat explained. “What it’s really transmitting to the non-patient is the muscle spasms.” The device doesn’t just show someone what it’s like to have Parkinson’s. It recreates what a specific patient is experiencing — in real-time, if necessary.

“We’ve seen it with the subjects we’ve tested, that it transforms them — they realize what it’s actually like,” said Fossat. “In fact, almost everyone that’s tried it — and I’ve tried it on maybe 150 people now — it’s at the end, when you flick the switch off that it truly dawns on them, that the patient doesn’t have that switch. That ability to say, ‘OK, I’m done now, turn it off.’ They don’t have that.”

It’s at the end, when you flick the switch off, that it truly dawns on them — and that the patient doesn’t have that switch.

Empathy can be a very important emotion when you’re caring for someone with a condition such as Parkinson’s. It can be useful for friends and relatives to experience tremor firsthand, of course, but Fossat also told us patients fare better with doctors that have higher levels of empathy. He and his team are currently planning a study that will attempt to quantify how much SymPulse can increase empathy, and for how long.

However, the hardware isn’t good for empathy alone. Fossat wants to help doctors treat patients from across the globe. Rather than simply listening to the description of symptoms over the phone, SymPulse could let them feel the patient’s condition.

“Especially with the cost of the hardware being so modest, or virtually negligible, it makes it much easier to do telemedicine like that,” he added. “You don’t have to send a giant videoconferencing system or an MRI scanner, you could send some kind of Arduino gizmo, and have the patient wear it.”

Much like the work being done by Liftware, Klick has been aided in its research and development by the availability of off-the-shelf hardware that promotes quick-fire prototyping, which Fossat describes as “transformative.” Now that there’s no need to order custom circuits from abroad during the early stages of design, iterative work that would once have taken months, now takes days.

The next step for Klick is getting its hardware properly accredited. There are numerous medical gadgets out there that claim to do great things, but Fossat knows from his experience with doctors that he needs to take a scientific approach if the hardware is going to be put into practice. “We want to make sure that this thing is validated,” he said. “I want to make sure that we validate what we do, and that we have proof and backing for our claims.”

Help Where It’s Needed

There was a time when it took an enormous amount of resources to create a new piece of tech — especially one that performed a function no previous product had. But that has changed over the last decade. Today, it’s much easier to grab a single-board computer, add any necessary external components, and run purpose-written code to produce the intended result.

This means companies like Klick and Liftware can design devices that cater to Parkinson’s sufferers, who make up a relatively small proportion of the global population. Custom technology is more workable than ever before, and that’s sure to help groups of people who can benefit from having hardware crafted to cater to their needs.

“There is a huge opportunity to bring technology and healthcare needs together, particularly for groups that are traditionally underrepresented in consumer technologies such aging populations or people living with disabilities,” Pathak told us. “Technology can help people with certain medical conditions maintain greater independence and improve their quality of life and the more we as technologists can meet their needs, the better off we all are.”

Innovative treatments for Parkinson’s disease are just one example of the growing symbiosis between the technology industry and medicine. In the future, we may see even rarer conditions receive attention from talented engineers and designers. It might not be possible to wipe out a disease like Parkinson’s, but it’s finally possible to find useful, affordable solutions for the people affected by it.