Most people think of space as a flat sheet: You travel in one direction, and you end up far from your starting point. But a new paper suggests that the universe may in fact be spherical: If you travel far enough in the same direction, you’d end up back where you started.

Based on Einstein’s theory of relativity, space can bend into different shapes, so scientists assume the universe must be either open, flat, or closed. Flat is the easiest shape to understand: it is how we experience space in our everyday lives, as a plane in which a beam of light would extend off into infinity. An open universe would be saddle-shaped, with a beam of light bending across the curvature. And a closed universe would be a sphere, with a beam of light eventually looping back around it to meet its origin.

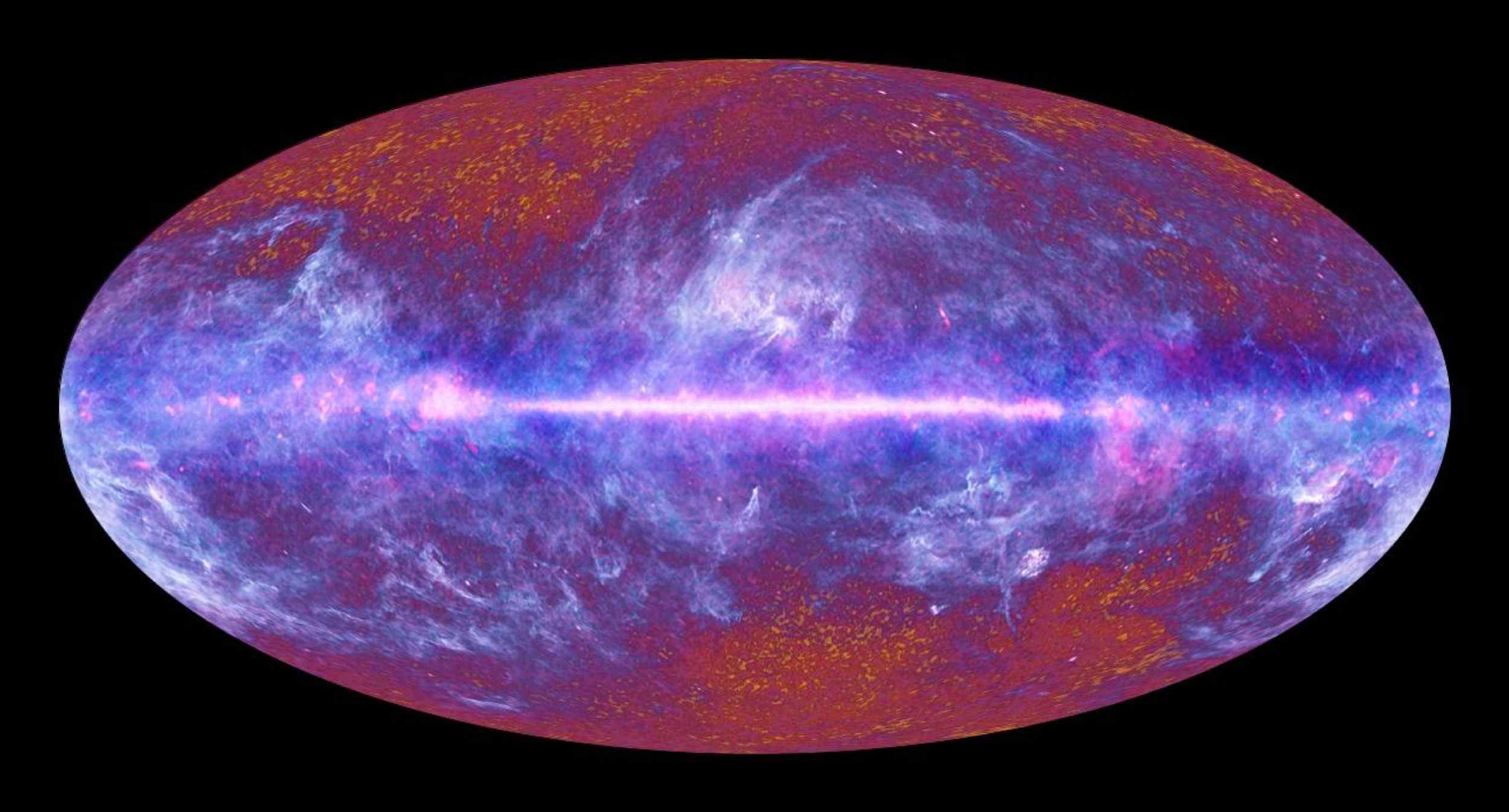

In order to tell which shape our universe is, scientists can look at a phenomenon called the cosmic microwave background (CMB). This is the electromagnetic radiation which remains from the Big Bang, also called “relic radiation.” It fills all of space and can be detected with a sufficiently powerful radio telescope.

In the new paper, the scientists measured the fluctuations in the CMB using data from the European Space Agency’s Planck space observatory. We know that these fluctuations are related to the amount of dark matter and dark energy in the universe. And although we still can’t detect dark matter or dark energy, we do know approximately how much of each exists. So when the researchers found more strong gravitational lensing of the CMB than would be expected, they knew they had a clue to the shape of the universe.

The most obvious explanation for these findings is that the universe is closed, not flat as previously thought. This would be a dramatic finding, to such a degree that the researchers called it a “crisis for cosmology.” However, there are complications which mean we cannot be sure if the universe is definitely closed. For example, the universe is constantly expanding, but researchers disagree on how fast this is happening, making it harder to predict the curvature of the universe. There are also other analyses of Planck data which strongly support the idea of a flat universe.

For now, the shape of the universe remains an open question. The research is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.