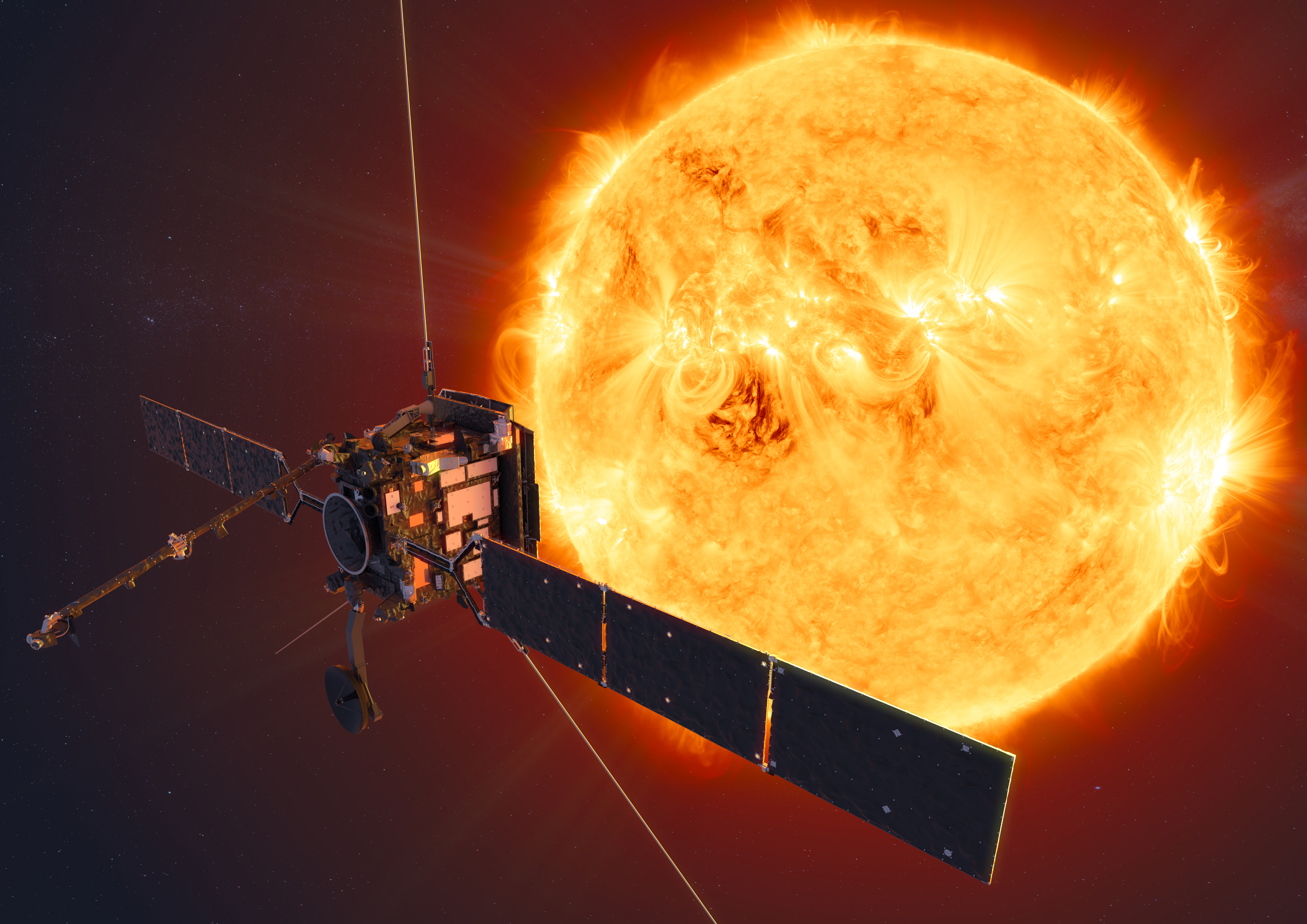

On Sunday, February 9, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) are banding together to launch a new mission to study our sun up close: The Solar Orbiter, which will peer at previously unseen areas of the sun to learn about the complex inner life of our star.

Imaging the sun’s poles for the first time

The mission will go where no observer has gone before: Over the north and south poles of the sun. Imaging the poles is particularly important for modeling space weather, as this requires an accurate model of the entire magnetic field of the sun. Additionally, the poles are thought to play a role in the cycle of sunspots — dark blotches that appear on the surface of the sun and which come and go in an approximately 11-year cycle. Scientists still have no idea why this 11-year cycle exists, but looking at the magnetic fields of the poles could provide an answer.

With its advanced imaging instruments on board, the Solar Orbiter mission will be the closest any sun-facing cameras have gotten to the star. “It will be terra incognita,” said Daniel Müller, ESA project scientist for the mission at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands. “This is really exploratory science.”

Keeping the orbiter safe from the heat of the sun

The Solar Orbiter will enter a highly elliptical orbit, meaning it travels around the sun in an oval shape, coming closer at some points than at others. This brings with it challenges of temperature management, as Anne Pacros, payload manager at ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands, explained: “Although Solar Orbiter goes quite close to the Sun, it also goes quite far away. We have to survive both high heat and extreme cold.”

These temperatures fluctuate from minus 300 degrees Fahrenheit in the cold of space, all the way up to 932 degrees Fahrenheit at its closest point to the sun, 26 million miles away. To handle this variation, the orbiter is equipped with a 324-pound heat shield which can reflect away the tremendous heat and radiation found close to the sun, and which can withstand temperatures of up to 970 degrees Fahrenheit.

The shield consists of layers of paper-thin sheets of titanium foil, which is highly reflective of heat without being too heavy. These layers are placed over a base of aluminum, which is honeycomb-shaped to be strong but also lightweight, and is covered in more foil insulation. The base provides strength, with titanium brackets attached to it that hold the layers of foil in place. Importantly, there is a 10-inch gap in the shield which allows heat to vent out into space, as well as peepholes for the instruments aboard to see through.

And there’s one last piece to the shield, but is rather old-fashioned for such a modern craft. The shield is coated in a dark powder similar to charcoal or the pigments used in ancient cave paintings, which protects the craft from ultraviolet solar radiation. “It’s funny that something as technologically advanced as this is actually very old,” Pacros said.

Launching into a highly inclined orbit

The launch takes place at Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, with the craft aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket. To get to its target, the orbiter will use the gravity of both Earth and Venus to swing away from the ecliptic plane. This is the flat plain, roughly coming out from the sun’s equator, in which most bodies in the solar system reside.

By swinging out of this plane, the orbiter will be able to see the sun from a different angle, and to see new areas of it like its poles. “Up until Solar Orbiter, all solar imaging instruments have been within the ecliptic plane or very close to it,” Russell Howard, space scientist at the Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C., and principal investigator for one of Solar Orbiter’s 10 instruments, said in a statement. “Now, we’ll be able to look down on the sun from above.”

Across its mission, the orbiter will reach an inclination of 24 degrees above the equator, possibly moving up to 33 degrees if the mission extends for three years as planned.

Two solar missions are better than one

The Solar Orbiter isn’t the only instrument we have to examine the sun. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe entered orbit around the sun in 2018, and has already captured footage of solar winds and the first image from inside the sun’s atmosphere. The Parker Solar Probe travels closer to the sun that the Solar Orbiter does, coming within just 4 million miles of the sun, but it has limited equipment on board.

The idea is that the two craft will work in tandem, with the Parker studying the sun up close while the Orbiter collects more data to contextualize the Parker findings. Additionally, both craft can be used to measure the same streams of solar wind at different times.

“We are learning a lot with Parker, and adding Solar Orbiter to the equation will only bring even more knowledge,” said Teresa Nieves-Chinchilla, NASA deputy project scientist for the mission.

Timeline for the mission

Following its launch, the Solar Orbiter should perform its first flyby of Venus in December 2020, then make its one planned flyby of Earth in November 2021. By 2022, it will makes it first close pass of the sun, coming within 31 million miles. By 2025, it will reach an inclination of 17 degrees, and by 2027 it will reach 24 degrees inclination. If the mission is extended, it could continue on for an extra three years on top of its seven-year main mission.