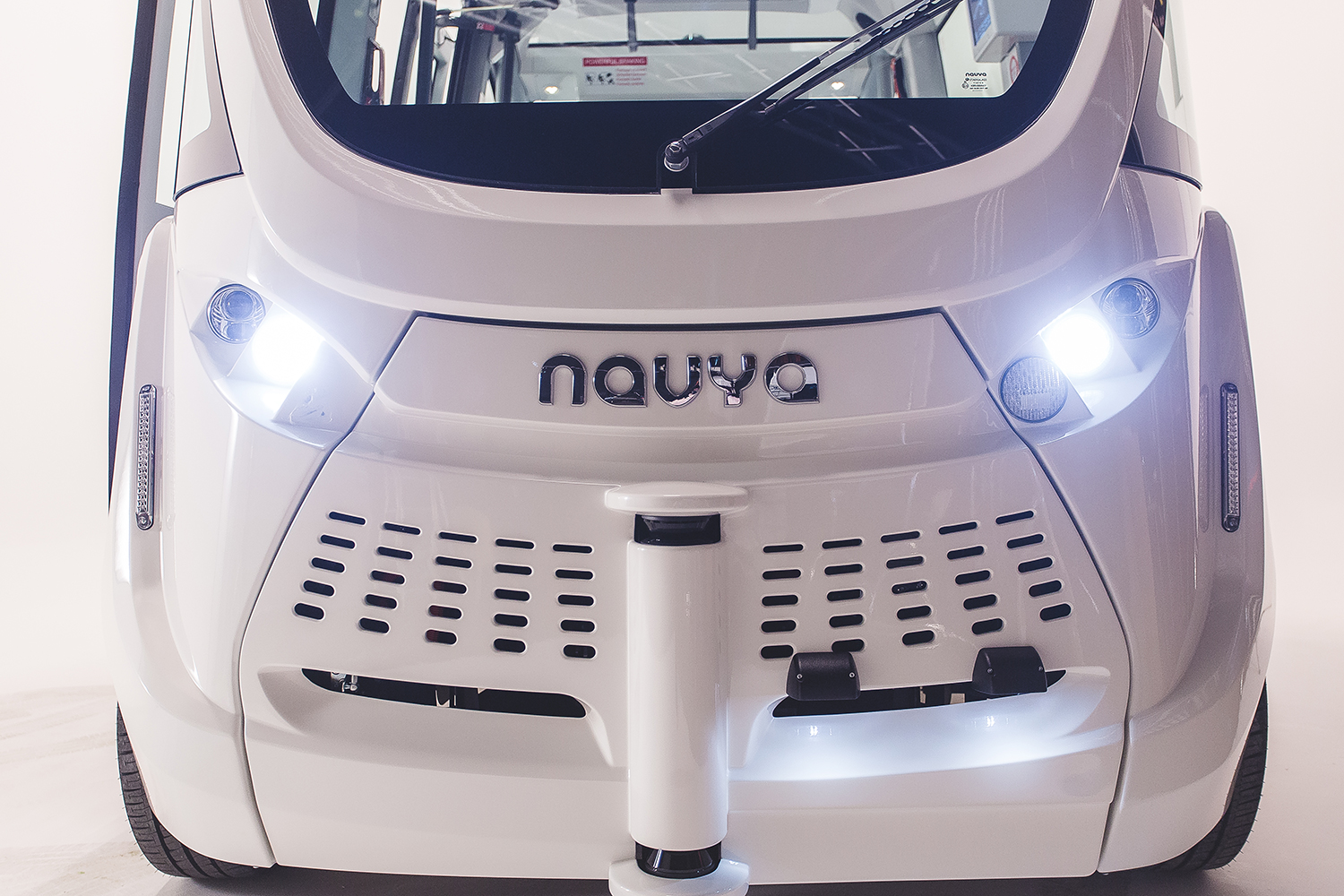

The first self-driving vehicle many people will experience firsthand may not be a car, but rather a public shuttle. While they may not be as sexy as sleek autonomous sports cars zipping down a highway, slower, boxy shuttles present more of a practical–and less risky–self-driving electrified solution to moving people around cities. But these shuttles will confront the same hurdle that all autonomous vehicles will face: a high price tag.

“The price is so high today,” Christophe Sapet, the CEO of French autonomous vehicle company Navya, told Digital Trends. “You can’t imagine how someone could afford $200,000 or $500,000 for a self-driving car.”

Cities across the globe are installing technology to gather data in the hopes of saving money, becoming cleaner, reducing traffic, and improving urban life. In Digital Trends’ Smart Cities series, we’ll examine how smart cities deal with everything from energy management, to disaster preparedness, to public safety, and what it all means for you.

Instead of selling vehicles for private ownership, Navya’s strategy is to build small, electric autonomous shuttles with a $300,000-plus cost that can be amortized over time by municipalities, campuses, and large corporate parks working on smart city-style projects. The company recently christened a new plant for producing its shuttles in Saline, Michigan, about 40 miles west of Detroit. The factory will initially build shuttles for projects like the one in Candiac, Quebec, and later hopefully expand to produce robotaxis, for a forthcoming pilot in Lyons, France, and even cargo tractors for airports.

Navya already has pilot projects underway in 18 different countries around the world, Sapet told us.

“Most people are ready to accept this kind of transportation,” he said, discussing environments that seem ideally suited to autonomous transportation, such as retirement communities and college campuses. But even with pre-programmed routes and pickup locations, “we are running these vehicles in a very complicated environment,” so there’s a considerable amount of learning still to be done.

“We also need to see how people react to it,” Sapet added. Discussing challenges that include everything from pranksters to vandalism, Sapet noted that these are realities that the new vehicles will have to contend with. Currently, the shuttles, while autonomous, still have human minders onboard who can stop the vehicle in case of trouble, but in the future the goal is to achieve full autonomy.

So, what happens when a passenger misbehaves?

One project Navya is currently running is at the University of Michigan. Contending with boisterous students who have spent the evening in a nearby pub is just one example of situations a shuttle might have to deal with on a college campus. In the future, onboard cameras will alert remote monitors if a passenger gets into trouble or falls asleep on the bus. And technology suppliers like Valeo are already working on systems that can read people’s expressions to determine risk, Sapet said.

Naturally, cities are also concerned about integrating such self-driving electric shuttles into their current transportation systems. Working out such logistics is not an easy matter — meshing them with train schedules, inclement weather, sporting events, holiday traffic. So Navya has partnered with Keolis, which handles such supervisory systems for many cities. Still, Sapet argues its easier than trying to deploy other public transportation systems.

“It takes years and billions of dollars to build out public transportation systems,” he said, such as light rail. “But [autonomous shuttle] is easy to deploy.”

NHTSA puts the brakes on driverless transport

Deploying driverless shuttles is easy, if government regulations can catch up, as another French transportation company recently found out the hard way. Transdev, which is operating self-driving shuttles in a smart community in Florida, was surprised by a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration announcement that it wanted the company to stop transporting school children in the smart community of Babcock Ranch in Florida, on Transdev’s EZ10 Generation II driverless shuttle.

Related reading

- The history of self-driving cars

- Ford’s self-driving cars hit the streets of the nation’s capital

- Waymo self-driving cars are now covering 25,000 miles a day

- BMW to introduce ‘safe’ fully autonomous driving by 2021 with iNext

In a press release, NHTSA said that having school children on the shuttle was “unlawful,” but such shuttles have been used to transport people of all ages going back to November of 2017, according to Transdev. The new route took a few children on a three-block distance on private roads to the school as part of additional testing. Even though Transdev had not received an official notice from NHTSA, the company said it would suspend the route until proper regulatory issues — if any — had been sorted out.

“It’s the same shuttle we’re running on other routes, and it’s not run by the school,” Lisa Hall, a spokesperson for Babcock Ranch, explained to Digital Trends in a phone interview. “It’s community transportation and not a school bus.”

The shuttle itself only travels at 8 miles an hour, but both Babcock and Transdev said they would work to address any concerns NHTSA might have.

Using driverless shuttles to attract high-tech, wired residents

As an emerging smart community, Babcock Ranch focuses on sustainable technologies including solar power and healthy living initiatives. “It’s a living lab,” Hall said, who described it as a high-tech, wired community. “Mayberry meets the Jetsons.”

For Babcock, the incentive to participate in such pilot projects as the Transdev shuttle is obvious. “We want to attract multi-generational residents,” Hall said, pointing out that the more leading-edge projects they work on, the more it attracts other high-tech partners to initiate other projects.

The benefit to both communities and companies is the knowledge gained for future deployments. Adapting smart transportation systems to consumer response as well as new technologies is essential, and Babcock and Transdev are looking forward to on-demand shuttles.

Navya’s Sapet pointed out that being able to adapt to new technologies is also essential. “If a new sensor comes out, we can adjust it to our system in less than two months,” Sapet said.

How will communities fund these shuttles?

Communities and municipalities have to figure out new ways of financing and supporting these zero-emission self-driving shuttles. So Navya, for example, works with local governments to address issues on how to finance and insure systems in the new autonomous landscape. The company is working with AXA, the global insurance and asset management firm, to develop insurance solutions tailored to autonomous vehicles.

Of course, smart cities and smart transportation doesn’t just mean smart shuttles and robotaxis.

“We can do this with more than just people,” Sapet said, referring to other potential projects. Deliveries and cargo could also benefit from autonomous electric transportation. And Navya is already working with a partner to handle airport luggage transportation.

In other words, self-driving vehicles may not only help bring safer streets to communities, they could also mean never losing your luggage again.