Your sweat can reveal a whole lot about you — and a next-generation wearable skin sensor promises to analyze your perspiration to extract that information. Developed by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, the sensors can detect the individual components in your sweat. While that sounds kind of gross, Ali Javey, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at UC Berkeley, told Digital Trends that it could turn out to be pretty darn useful.

“Sweat analysis has so far been shown to be meaningful in a handful of cases,” Javey said. “Testing sweat [chloride ion] concentration is the gold standard for diagnosing cystic fibrosis, and monitoring sweating behavior has been a clinical practice for assessment of autonomic function. Sweat alcohol levels can indicate blood alcohol levels. Beyond alcohol, other chemicals, toxins, and contaminants — such as heavy metals and drugs — introduced into the body but not natively produced, are often excreted in sweat. [That means] that sweat testing can indicate exposure.”

That’s not all. Javey said there are other use cases for sweat testing that are yet to be fully demonstrated. For example, there is the possibility that localized sweat rate measurements, taken from just one small patch on the human body, could reveal whole body fluid loss. That makes it potentially valuable for athletes, who want to monitor for possible dehydration.

But while sweat turns out to be pretty versatile, analyzing it hasn’t previously been easy. It involves collecting and storing sweat samples for analysis in labs. That comes with all sorts of challenges, many of which could be overcome by wearable sweat sensors that conduct analysis immediately, autonomously, and at the point of sweat generation.

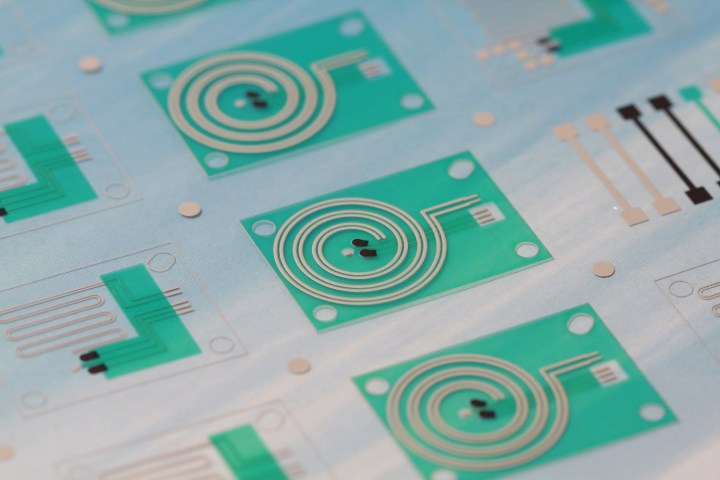

The team’s new sweat sensor design will be rapidly manufactured using a “roll-to-roll” processing technique that makes it easy to print sensors onto a sheet of plastic. Its creators liken this to printing words onto newspaper. The sensor can monitor sweat rate, along with the electrolytes and metabolites contained within sweat. It does this using a spiraling microscopic tube, or microfluidic, which wicks sweat from the skin. Measuring how quickly the sweat moves through the microfluidic makes it possible to determine how much a person is sweating. The microfluidics are also kitted out with chemical sensors for detecting the components of sweat, such as potassium, sodium, and glucose.

“Going forward, our goal is to continue using our sensors in large-scale human subject studies to explore how sweat parameters relate to the state of the body across athletic and medical applications,” Javey said. “In parallel, we have also shown in other papers the promise of this technology for drug monitoring and heavy metals.”

A paper describing the work was recently published in the journal Science Advances.