That is something a new research project from the U.K.’s University of Bradford aims to improve. What researchers there have developed is a method for — or so its creators claim — more accurately aging facial images, courtesy of some smart machine-learning technology.

“In our work, we teach the computer by presenting hundreds to thousands of face images and the corresponding ages,” Ali Maina Bukar, a researcher on the project with expertise in facial analysis and synthesis, told Digital Trends. “Thereafter, having learned the human aging process, the machine explicitly progresses images on the fly. This is a faster and less subjective technique.”

The algorithm the team developed captures the nonlinear shape and muscular variations of the human face as a way of “learning the pattern” of aging. Given an image, it first extracts the identity of the person and then maps it to the aging pattern it has learned, thereby modeling an age-progressed realistic image.

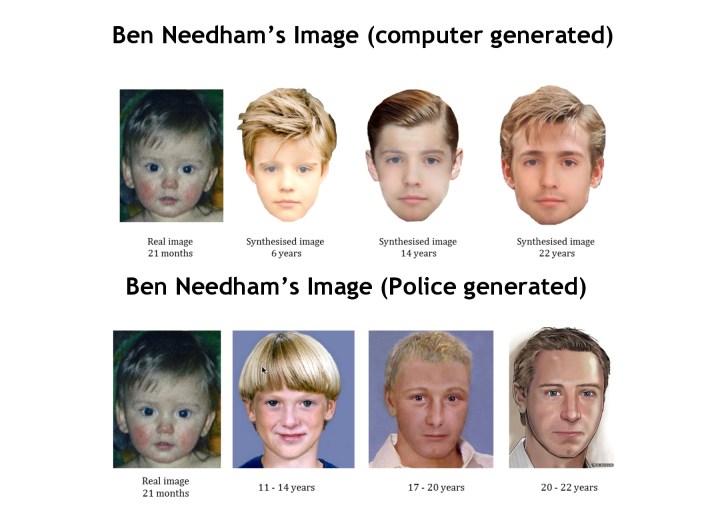

In their test case, the researchers used the algorithm to generate aged images of Ben Needham, who disappeared on the Greek island of Kos in 1991, at the age of just 21 months. Needham has never been found, but the algorithm enabled the investigators to create images of him as he may have looked at various ages. They believe that these images are more accurate than the ones used by the police; based on how well the algorithm has performed in other demonstrations.

However, while the hope is to eventually roll this AI-aging algorithm out as a police tool, Bukar notes there is still more work to be done. At the moment, the algorithm works on cropped images only, meaning that it doesn’t currently consider the subject’s hair in the same way that it does the face.

“We are working on enhancing it such that both face and hair can be generated,” Bukar said. “We hope this project gets accepted by the public and the police so it can be applied in real world. This is the main reason why we chose a popular subject — Ben Needham — in our experiment. It illustrates to the world our algorithm’s applicability and potential in the search for missing loved ones.”

A paper describing the work was published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.