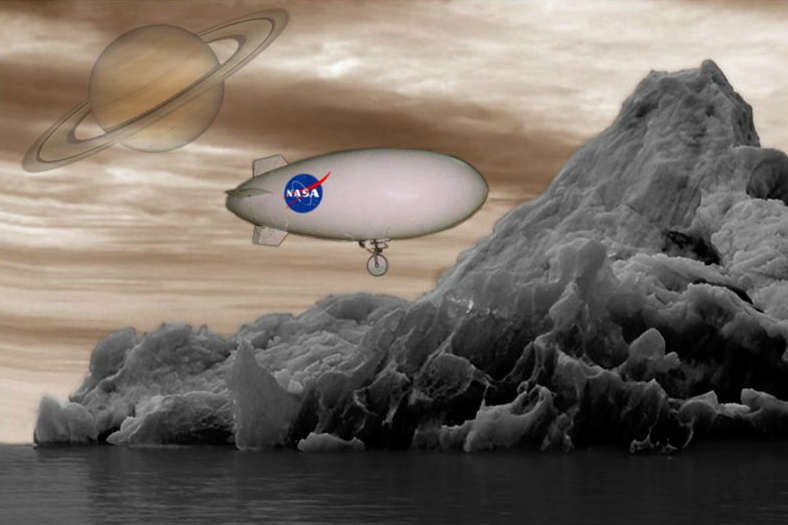

A blimp on Titan

The Cassini probe gave mankind its fist look at the Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. It is the only moon in our solar system known to have an atmosphere and researchers believe it may even host life . To prepare for future missions to Titan, NASA proposed a series of conceptual designs including a a small, helium-filled dirigible, known as the Aerover Blimp.

The zeppelin would utilize three propellers to circumnavigate Titan every one or two weeks. Aerover would be about 33-feet in length and 8-feet in diameter, or — as JPL rather oddly specified — “roughly the length and height of a stretch limousine.” The design calls for a small inflatable wheel along the bottom to cushion the blimp when landing on an array of rocky terrains and allow the unit to float on oceans of liquid methane. According to JPL, the concept is still under consideration, so the notion of piloting a remote-controlled blimp somewhere in the cosmos is still in play. At least for now.

Nuking the moon

Some of most bizarre space missions were a result of the hysteria and seemingly bottomless military bankrolling during the Cold War. In 1957, the successful launch of Sputnik sent the top US military brass into panic mode. Seeing as communist world domination was the next logical step after the achievement, the US Air Force decided it needed to flex its own muscles to save face — and the best way to do this was obviously to nuke the moon. As the saying goes: If you can’t beat ’em, irrationally nuke something … anything.

This program, known as Project A119, remained a secret for more than 40 years until Leonard Reiffel, a physicist who worked on the project, made these mission details public, stating that at the time, the “Air Force wanted a mushroom cloud so large it would be visible on Earth.” Eventually, cooler heads prevailed and the Air Force put its nuclear toys away, thankfully setting its sights on more pragmatic ambitions — like putting humans on the moon.

An orbiting battle station

As noted previously, the world’s two superpowers were rather trigger-happy during the peak of the Cold War. Both sides were developing a myriad of clever ways to effectively vaporize us as a species. Needless to say, these tricked-out death machines weren’t limited to an all-out war here on earth. The Soviets were designing a space station with an on-board “cannon” just in case. And unlike many of these other concepts, this orbiting battle station actually made it to outer space.

The Solyut-3, an early Soviet space station, orbited the earth locked and loaded with a 37-pound rapid-fire cannon capable of shooting more than 5,000 shots per minute and hitting targets nearly two miles away. The overall design did have one rather awkward design flaw, though. To aim the gun, the astronaut had to maneuver the entire 20-ton space station.

Fortunately, the Cold War ended without any full-scale galactic gunslinging, but the Soviets did fire the cannon on at least one occasion. In 1975, just before the space station was set to de-orbit, the the Soviets remotely fired 20 shells — all of which were said to have burned up in the atmosphere.

Triple-planetary flybys

In the 1960s and ’70s, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union were interested in manned flyby missions of Mars and Venus. For the U.S., such flybys were possible using upgraded Apollo mission hardware. In 1966, a the NASA Joint Action Group (JAG) proposed a four-man Mars flyby that would leave Earth in September 1975, arrive at Mars in 1976, and then return to Earth in 1977.

The team also noted a “triple-fly” opportunity involving both Mars and Venus. This theoretical mission would leave Earth in May 1981, fly past Venus on December 28, 1981, boomerang around Mars on October 5, 1982, and again past Venus in the spring of 1983 before returning to Earth on July 25, 1983. Unfortunately, nearly four decades have passed since these rather lofty ambitions without manned flybys of either planet. Perhaps that will change in the near future. In Musk we Trust.

Massive “moon buggies”

To better maneuver the lunar landscape, NASA commissioned General Motors with the task of designing a series of manned lunar vehicles, and the Mobile Laboratory (MOLAB) was a 1965 prototype. At 20 feet in length and weighing more than four tons, the closed-cabin MOLAB was a beast of rover. The pressurized vehicle was designed to function as a geological laboratory, capable of sustaining two astronauts for up to two weeks. The rover had a top speed of 21 miles per hour and a a range of more than 60 miles.

The unit packed a modified Corvair engine under the hood and was so massive it would’ve taken a Saturn rocket to launch it to the moon. Ultimately, NASA eventually shelved plans for its lunar monster truck and instead went with the slightly slimmer, more practical moon buggy design. Nonetheless, at least a few individuals had the opportunity to test drive the bigger, badder version in the New Mexico desert before it was decomissioned. And we did recently get a peek at this badass Mars Rover concept.

Probes to distant stars

Alpha Centauri is about 4.37 light-years (or about 26 trillion miles) from Earth. Nonetheless, a mission known as Project Longshot involved sending a probe to our celestial neighbor. The vehicle itself was to be assembled at the space station and launched on site. The probe would use a fission reactor to then traverse the galaxy for more than a century before reaching its destination. As one could imagine, Project Longshot was a prospective longshot to begin with and never received funding. At the moment, Voyager 1 remains our best shot at reaching another star system. In roughly 40,000 years, the spacecraft will be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than our sun. Mark your calendars.