I vividly remember witnessing speech recognition technology in action for the first time. It was in the mid-1990s on a Macintosh computer in my grade school classroom. The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once wrote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” — and this was magical all right, seeing spoken words appearing on the screen without anyone having to physically hammer them out on a keyboard.

Jump forward another couple of decades, and now a large (and rapidly growing) number of our devices feature A.I. assistants like Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa. These tools, built using the latest artificial intelligence technology, aren’t simply able to transcribe words — they are able to make sense of their contents to carry out actions.

But voice can do so much more than that. One of the reasons tools like Zoom experienced increased popularity during the pandemic is the nuance that voice offers. We can convey almost as much information with our tone as we can through the words that we choose.

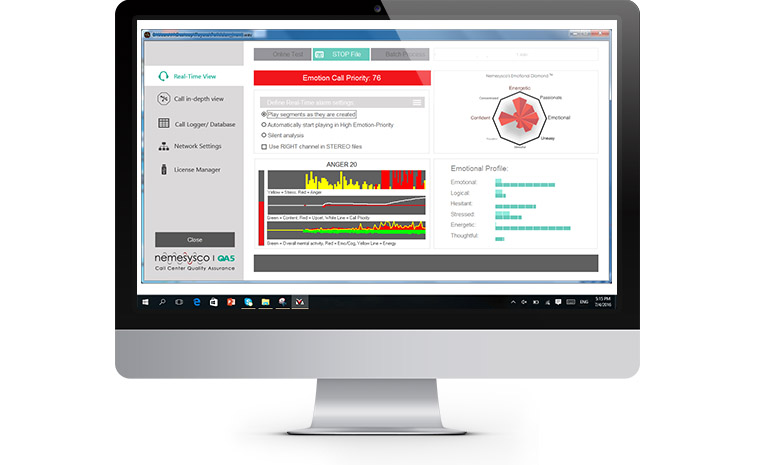

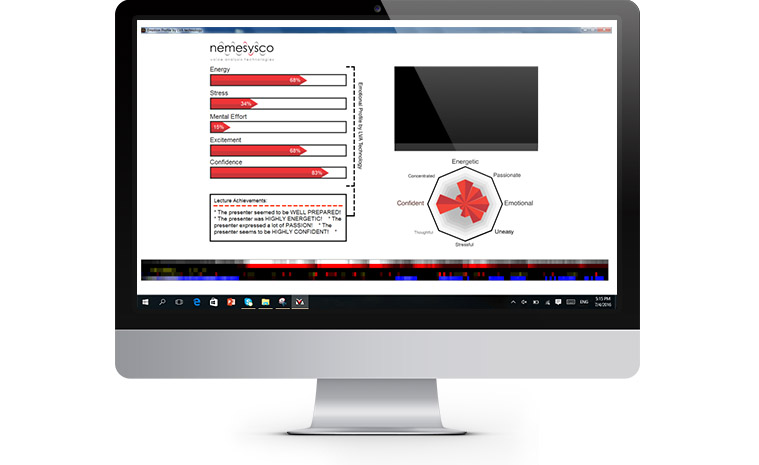

However, for the most part, current-gen voice recognition tools ignore this. Nemesysco, an Israeli tech company that specializes in voice-based emotion detection, wants to right that wrong. In doing so, it could take voice recognition technology to the next level, creating smart voice recognition that doesn’t just understand us but actually understands us. This, it believes, could make tomorrow’s smart assistants even smarter, offer new ways of interacting with the world, and even potentially help decide whether or not you get that next job promotion you’ve been hankering after.

Get ready for the world of “affective computing.”

Hiding your emotions

I’m feeling stressed. Actually, that doesn’t tell the whole story. I’m feeling stressed, joyful, aggressive, upset, and energized — as well as passionate, happy, engaged, hesitant, uneasy, sad, and almost certainly a handful of other emotions that Amir Liberman, founder and CEO of Nemesysco, hasn’t been measuring. Some of these emotions are more noticeable than others. In certain cases, they’re big, broad, and loud. In others, they’re quieter trace elements similar to the tiny, accidental dusting of peanuts you might find in a packet of chips. But they’re there on screen all right, bouncing up and down like the bass and treble audio frequencies on a hi-fi.

Liberman isn’t exactly putting me through the wringer. He’s just asking me to tell him what I’ve done with the day so far: A pretty typical morning that’s consisted of being woken just before six by my 3-year-old daughter, eating breakfast, helping her get dressed and cleaned up, taking her to day care, spending half an hour answering emails, then jumping on a call for a chat about emotion-sniffing A.I.

Unlike the sentiment mining technology which, for example, combs Twitter feeds to ascertain the large-scale emotional reaction of people to major news events, everything Nemesysco does when it comes to emotional quantification is based on the voice sounds of the speaker. You could be talking about an uneventful Thursday morning or the worst day of your life; what matters isn’t the things you say but how you say them. At least anecdotally, it seems to work, too. While I try to speak evenly (and, as noted, my morning hasn’t exactly consisted of high drama), little biomarkers of stress, amusement, and other indicators spike at the points you might expect them to during my monologue.

According to Liberman, the voice contains — or, at least, Nemesysco’s Layered Voice Analysis A.I. is able to extract — 51 parameters, which can then be isolated and associated, broadly, with 16 emotions. “The uniqueness about them is that they’re all uncontrolled, they’re all subtle,” he told Digital Trends. “And they all relate to true emotions, not the ones that we try to broadcast.”

From lie detectors to 11,025 data points

Nemesysco started building its emotion-spotting voice recognition tool 24 years ago as a lie detector for use by security forces. “Never had any intention to make a cent from it,” Liberman wrote me in an email a few days after we spoke. “The idea was to build a lie detector that will be simple to use in the entry gates of Israel to prevent terror.”

At the time, the idea of solving this problem with A.I. was widely ridiculed. “When we started, A.I. was a bad word,” he recalled. “When I said, ‘we’re going to be using A.I. and emotions,’ people told me, ‘Whatever you do, don’t mention A.I.’ … ‘Absurd’ was one of the [nicer] names I was called.”

Nemesysco’s technology has since expanded far beyond the binary “truth or lie” premise it was founded on. But some of that notion of truth-seeking, of forensically probing the subtleties of speech for imperceptible vocal patterns people aren’t even aware they’re exhibiting, remains. “When you talk about the emotions in the voice, there is a very important distinction between what we try to broadcast and what we actually feel inside,” Liberman said. “We’re not cut and dry: we try to mask our voice and how we feel in many cases.”

A person would typically struggle to spot emotions on a waveform. Nemesysco’s system uses an 11Khz sampling rate, which results in 11,025 points of data generated every single second. Finding emotion in that quagmire of data points is like finding an angry needle in a haystack. For some “basic” emotions, “if you know where to look, you can make approximations in your head,” he said. “Of course the PC does it much better and faster.” For most emotions, machine learning A.I. is required. As Liberman noted: “We use machine learning to identify aggression, sadness, happiness. These are very complicated emotions, in terms of the complexity in the mind. It was very hard [for us to initially] find them.”

“A phone who is really your friend”

The idea of giving emotion-sensing to machines is one that has long been explored by science-fiction writers. Take a character like Data, the android from Star Trek: The Next Generation: No matter how much of a handy information repository he may be, he experiences communication challenges with the Enterprise crew early on because he doesn’t understand certain nuances of human behavior.

A large part of the promise of real artificial intelligence is built on the notion of being able to model or simulate human cognitive abilities. No cognitive ability is more human than expressing emotions. Being able to grant machines the ability to sense emotion is not the same thing as making machines themselves emotional. Emotion-sniffing technology could help us achieve greater understanding of ourselves, potentially pulling off the tricky feat of giving us objective, rather than subjective, data about emotions. “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” as the old saying goes.

In some cases, being able to understand the emotional state of users could help make technology work more intuitively — or perhaps more safely. “I strongly believe that making A.I. decisions without taking into account my emotional state and my personality would never be as good as [doing it with this in mind],” Liberman said.

He reels off potential applications: A robot that entertains your kids while monitoring their wellbeing; an app that helps you optimize your mood to focus on your goals; a car with an autopilot mode that limits your speed or takes the wheel when it knows you’re stressed. “Think about a phone who is really your friend,” he wrote me.

Your next job promotion

Right now, a big push for the company is the use of Nemesysco tech to potentially help decide on job promotions for people. The company has a joint research project with the Faculty of Psychology at Russia’s Lomonosov Moscow State University to “establish quantifiable methods for measuring the aptitude qualities and personal competencies of job candidates and employees being considered for promotions, including stress, motivation, teamwork, leadership capabilities and more.”

The idea of being turned down for a job because our voice suggests we’re wrong for it sounds, well, terrifying.

The testing method was recently applied to the corporate restructuring initiative of a large industrial company in Russia. As part of the initiative, the voices of slightly fewer than 300 executives and senior-level managers, all up for promotion, were analyzed during discussions with the company’s HR team, as were verbal responses given to a questionnaire. The test concluded that approximately 28% of candidates being evaluated for possible promotions were not suitable and would have a tough time coping with their new duties.

The idea of being turned down for a job because our voice suggests we’re wrong for it sounds, well, terrifying. Liberman said it’s not as simple as that. The idea is not that a person’s voice dictates their likelihood of getting a job promotion, but rather that it is one of many factors that might inform such a decision. In an interview, a person may be asked about their last experience managing a team of people in a certain context. If their voice reveals enthusiasm and confidence as they retell the story, that might indicate suitability. If their vocal signals suggest trepidation and upset, it could mean the opposite.

“By clustering these emotions into a report, we can then say one of the things you enjoy doing and what are the things you prefer not to be doing,” he said.

Sentographs everywhere

In 1967, an Austrian-born scientist and inventor named Manfred Clynes built a machine for measuring emotion. Clynes, a child prodigy who once received a fan letter from Albert Einstein regarding his piano playing, called it the “sentograph” after the Latin word sentire, meaning “to feel.” The sentograph measured changes in directional pressure that were applied to a button a person could press. Reportedly, a single finger press could reveal anger, reverence, sex, joy, and sadness. The results were published in a 1976 book by Clynes called Sentics.

As with many pioneers, Clynes’ work on sentics did not amount to much during his lifetime. Today, however, the field of “affective computing” is continuing to gain momentum. Researchers claim that they can accurately predict emotional states based on facial expressions, heart rate, blood pressure, even app usage and phone records. And, of course, voice.

One of the trickier areas to navigate in this brave new world of emotion-sensing technology will be ensuring accuracy. Speech recognition is, in this way, comparatively simple. A dictation tool either dictates the words spoken to it or it doesn’t. The idea of unpacking emotions that even the user doesn’t realize they’re conveying is more challenging. There is a reason why lie detectors are not admissible in court. Ensuring that these tools work and are not prone to bias must be a top priority.

According to Liberman, everyone exhibits the same vocal tics his system is looking for. There is, a pitch deck for the company notes, “no age, gender, or ethnic bias.” Liberman told me that it is “cross cultural, it is cross ethnic groups, it is the same for everybody.” This is vital, especially as such tools move beyond laboratory research projects and into more and more areas of our lives.

The voice A.I. was trained with real people giving genuine emotional reactions. “Nothing in our research was conducted on fake voices,” he said. “Nothing. Everything we did, every model we built, was based on real emotions collected in real-life situations.”

Emotion-tracking A.I. is coming. In the same way that speech recognition — once a sci-fi dream, being industriously worked away on in a few high-end research labs — is now found on our phones, so too will affective A.I. become a fixture in our everyday lives. That is, if it isn’t already.

Who knows: It could even help give you the green light for your next big career promotion.