“I’m going to shoot you a link in the chat,” said Daniel Greenberg. “Just open it on your phone, and go into controller mode. Use the image on the screen to kind of guide you. But there’s also an onboard camera.”

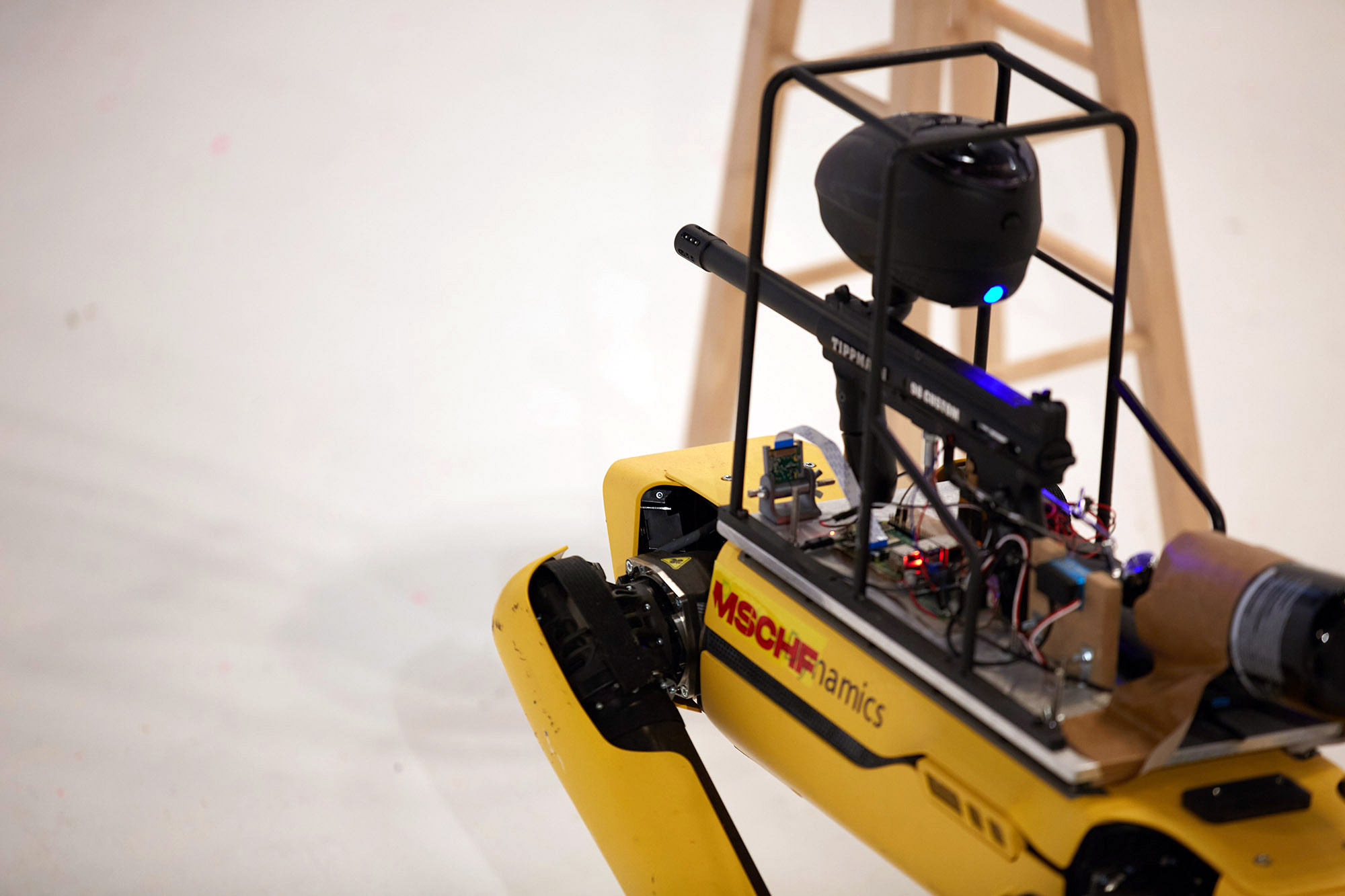

Thirty seconds later, I was remote-controlling a Spot robot — one of the quadruped, canine-inspired robots built by Boston Dynamics — as it charged around an empty art gallery performance space in Brooklyn, thousands of miles away, firing paintballs from a .68cal paintball gun mounted on its back. As ways to while away time during lockdown go, it certainly made a change from Zoom calls.

While I got to try out “Spot’s Rampage,” as its creators call it, late last week, this week it’s getting a much wider release. For a few hours on Wednesday, February 24 — starting at 1 p.m. Eastern/10 a.m. Pacific — anyone who wants to take the gun-toting Spot for a spin can do so by visiting an online link. All you need is an internet connection and an appetite for chaos.

“Every two minutes it’s going to pick someone at random to control it,” Greenberg told Digital Trends. “There’s no waiting list or data collection. It’s just, ‘be on the site, and if you’re lucky you’ll get to control Spot.’”

Not an official Boston Dynamics project

Boston Dynamics, the cutting-edge robotics company behind Spot, has carved out something of an unlikely reputation for itself as a viral hitmaker over the last several years. A recent video of its robots dancing to The Contours’ 1962 hit “Do You Love Me” has racked up close to 29 million views on YouTube. “UpTown Spot,” a 2018 video showing Spot grooving to Bruno Mars, has received almost 8 million. And “Hey Buddy, Can You Give Me a Hand?,” showing one Spot robot using a gripper attachment to open a door for another Spot, has been clicked on a mind-boggling 95 million times. Those are Jake Paul, Charli D’Amelio, or PewDiePie numbers. All for a dog robot pulling off cool tricks.

To be clear: Spot’s paint-firing remote control jaunt is most certainly not a Boston Dynamics production. Instead, it’s the work of MSCHF, a Brooklyn-based “ideas factory” collective that’s the closest thing the internet has yet produced to a Banksy. Every two weeks, MSCHF drops a new, ultra limited edition product for its (by now eagerly anticipatory) online audience. This could be anything from a dog collar that turns your pet’s barks into a stream of swear words to custom Nike “Jesus Shoes” sneakers filled with holy water to, yes, the chance to commandeer a $75,000 dog robot for a couple of destructive minutes in the group’s first-ever livestream.

When MSCHF first got its hands on a Spot robot (it finally went on sale last summer), the group of internet pranksters decided to use it as a platform for what may be their most controversial and eyebrow-raising project yet. “I think for a lot of our projects, we see them as sort of cultural Trojan horses that just get these conversations started,” Matt Rayfield, programmer at MSCHF, told Digital Trends.

“Every MSCHF drop is kind of like an onion, right?” Greenberg, MSCHF’s head of strategy and growth, said. “There’s so many layers. For the first layer, of course, it’s a — quote, unquote — ‘fun livestream.’ You get to control Spot, so there’s a novelty in the technology sense. That’s great. But then you kind of look deeper and see there’s a gun, and you’re like, ‘okay, maybe that’s a little dark, but it’s cool.’ And then you start looking even deeper, and you’re like, ‘okay, what does this actually say about Boston Dynamics, and what they’re doing, and where these robots are gonna go? MSCHF is, you could say, dumb enough to spend $75,000 on a robot to do this. But apart from us, you’ve got to really think, like, what other applications, or who has $75,000 to buy one of these? It’s not the people that are going to be making little YouTube videos, right?”

Gaming the Overton window

MSCHF’s principal concern with this project is how robots such as Spot are being used to subtly shift the public perception around what started off as a military research project. Spot’s antecedent, BigDog, was a quadruped robot built with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Today, military canine robots — although not necessarily those made by Boston Dynamics — are starting to roll out onto battlefields around the world. And yet people still think of these as the cutesy dog robots which boogied on YouTube to “Uptown Funk.”

“In a way, they’re shifting the Overton window for people to a place where, once they actually see one of these things in person, their first association will be ‘cute dancing dog,’” Rayfield said. “They are not going to feel as threatened.” Who knows, he asked, “Is this our future, in five to 10 years, where these dogs are patrolling the streets of cities with whatever on top of them?”

“All the videos Boston Dynamics puts out with the robot are geared towards this pop-culture meme mindset,” Greenberg said. “It’s like, ‘let’s see Spot do a dance. Let’s see Spot ride a skateboard. Let’s see Spot pulling a cart.’ Everybody that got early access to Spot, like all the YouTubers, did these cute, normalizing things with it. But when you start to think about it for a little bit, the way Boston Dynamics got its [work] off the ground was with funding from DARPA and the Navy. It’s sort of like, what was the actual intended use case for this robot? We’re not entirely sure.”

Spot’s Rampage is far from the first headline-grabbing endeavor Spot has been involved with. But it will mark a sinister first: The first time pictures of Spot with a gun have appeared online. Greenberg said, “I can tell you that, having seen it in person — I mean, all of us have — it’s incredibly frightening to see this robot walk towards you” with a gun mounted on top of it. Even if said gun is simply a paintball gun.

Spot’s makers speak up

Unsurprisingly, Boston Dynamics is none too pleased to see one of its robots affixed with a paintball gun. It is, after all, a far cry from Spot getting down to Bruno Mars.

Michael Perry, the VP of Business Development at Boston Dynamics, told Digital Trends that the company was approached by MSCHF several months ago about doing a Spot project. Perry suggested a project built around one of Spot’s newer innovations: The ability to use its robot arm to draw images. Wouldn’t it be great, he suggested, if they sent a couple of Spot robots to a gallery to do some live painting? “They said, ‘oh, that’s interesting,'” Perry said. “And then they disappeared.”

When MSCHF showed up again a while later, they revealed their plan for the paintball gun project. “We said, you know, we’re happy to help and — they’re obviously creative, and technically accomplished folks — but we were concerned that putting a gun on the robot falls outside of the things that we want people to do with Spot,” Perry said.

He continued that, “With any customer, police, government — even folks like MSCHF — we’re as clear as possible that the robot should not be used to harm people, should not be used to intimidate people, and can’t do anything illegal. If anything falls outside of that use case, we often turn the sale down. Funnily enough, two or three months ago, I turned down a pretty lucrative sale to a haunted house that wanted to use our robots to create a jump scare. That falls outside our terms of service. We were clear with the customer that we can’t conduct that sale.”

Perry said that, while Boston Dynamics has taken DARPA funding before, it’s not building weaponized robots for the military. Spot, in particular, is a consumer-facing technology, rather than one that is designed to be used to hurt people. While it has been used by groups like the Massachusetts State Police, this is about taking humans out of potentially dangerous situations; not helping to create those situations.

“The type of thing that MSCHF is portraying is really in line with the mainstream storytelling around robotic technology, which is it’s sentient, it’s here to hurt people, it’s an instrument of power,” Perry said. “[That] certainly doesn’t align with Boston Dynamics — and in many cases doesn’t align with reality in any real, meaningful way.”

According to Perry, the challenge for Boston — and the reason it leans so hard into the lighthearted videos — is because it has to set the dystopian record straight.

“The challenge that we have is trying to tell people that this technology can be really beneficial,” he said. “Because if you look at something like this, and your immediate perception is, ‘Hey, this is here to hurt me,’ then you’re really going to miss out on a lot of the positive and useful benefits of this type of robot. We’ve seen Spot go into mines that otherwise might potentially collapse on somebody, or go into irradiated environments that otherwise a person would have to go into, exposing themselves to chemical or radiation risks. Of course, the dancing and theme park applications are great because it’s a creative use of robotic technology … but there are life-saving, meaningful ways that this technology can be used.”

The kill-switch?

So will this week’s event, just a couple of days away, take place? One potential hurdle the MSCHF team mentioned was their belief that Boston Dynamics has a kill-switch of sorts that stops the robot from working if its creators do not like how it is being used.

“Reading through the documentation they gave us, it [suggests that they don’t] want you to do certain things,” Rayfield said. “Specifically, they don’t want you to like cause violence, obviously. But they seem to imply that they have some way of shutting [Spot] down if they don’t like what you’re doing with it … It’s kind of weird. You buy this thing outright — like, we’re not leasing it. They do have a lease option, but we’re not doing that — and yet, they still can basically revoke your access.”

— Boston Dynamics (@BostonDynamics) February 20, 2021

Perry clarified to Digital Trends that there is no immediate way of bricking the robot instantaneously. Nonetheless, if Boston Dynamics finds that its terms of use have been violated, it can revoke a license that stops the robot from being able to connect with the Boston Dynamics server for periodic firmware updates. “If we find out that the serial number [of a robot] that we sold is being used in illegal or harmful way, we will revoke that license and the robot won’t be active anymore,” he said. “It’s not something that we can reach into the back-end of the robot and flip a switch [to deactivate it.]”

However, he noted that it’s “unclear” if the paintball project violates the terms of service. “We’re evaluating our legal options here,” he said. “But, at the end of the day, they’re creative guys, they’re going to do what they do with the robot. So we’ll see what happens.”

Is Rayfield upset about the slight possibility that MSCHF’s plans could fall through at the 11th hour? Of course not.

“Obviously, if they shut it down, that will be a whole second wave of press, right?” he said. “On our end, that’d be great for the project because, conceptually, there’s going to be [this reaction] like, ‘oh my god, Boston Dynamics just bricked this.’ What does that say about what they don’t want people to see?”