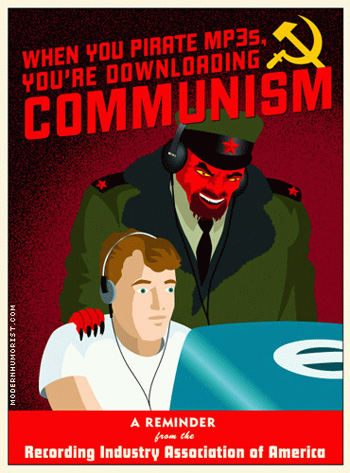

“No two ways about it: Piracy is legally and morally wrong.”

We’ve all heard it a million times. We’ve heard the analogies to walking out of a store with a CD under your jacket, sending software developers straight to the unemployment line or ripping food right out of a poor key grip’s mouth. And for some of us, we’ve even seen people we know ensnared by the law when they finally get caught gorging on free motion pictures and music.

Like drivers who slow down to pass a state trooper ticketing another driver, then quickly slam on the gas to get back up to 85 though, not everyone fears the reaper. After all – who hasn’t questioned whether Jay-Z and his record company really need another $12.99, scoffed at paying $10 for a single movie ticket, or wondered why they should pay money for a video game crippled by DRM when they could simply pirate a limitation-free version? The reality is that quite a few people are willing to take the risk and live dangerously.

But what is that risk, anyway? The odds of the RIAA knocking at your door are a lot harder to judge than the odds that you’ll eventually whiz by a highway median with a cop parked behind the bushes. And the consequences are potentially a lot more severe.

Crunching the Numbers: Your Odds of Getting Caught

Ten years after the RIAA first busted into the party of unlimited Backstreet Boys and Blink 182 swapping known as Napster, we now have plenty of data to examine when it comes to piracy. And the conclusions are pretty interesting.

The question, of course, is how many of these steal-from-home thieves were caught. That’s a number in some dispute. The RIAA started chasing individual file sharers back in 2003, then ended the offensive in 2008, leaving us a finite number of people to look at.

How many ended up in the nets? Estimates range from 18,000 to 35,000, depending on who you ask. Many reputable sources, including Pew, cite the 35,000 figure, but as an RIAA spokeswoman clarified to Ars Technica, that number most likely represents the number of cases, which is different from the number of people caught because many ended up with two cases – first an anonymous Doe, then again as named defendant. Meanwhile, the Electronic Freedom Foundation maintains that “well over 28,000 individuals” have faced lawsuits, either threatened, filed, or settled. Which is the number we’ll use.

What about the MPAA? Unlike the RIAA, which built a name for itself stringing up individuals like students, clueless parents and single mothers for file sharing, the MPAA has largely strayed from the practice (with some rare exceptions). Instead, the organization finds itself more frequently locking horns with the ringleaders who tape, rip and distribute copyrighted movies, like the infamous Pirate Bay. In other words: not you. (We hope.) The same goes for the Business Software Alliance, which tracks software piracy, but dedicates most of its legal resources to chasing major distributors of pirated goods, and large businesses that use them.

The good news after all of that math: The heaviest threat has passed. The RIAA officially waved its white flag back in December 2008, ending its mass lawsuit strategy in favor of ISP warnings and rare lawsuits for heavy file sharers and those who ignore warnings.

What’s the Ticket, Officer?

Enough odds. What do convicted file sharers actually have to shell out?

More typically, accused infringers settle upon first contact with the organization, dodging legal battles entirely and keeping out of the public eye. According to the Electronic Freedom Foundation, “Most lawsuit targets settle their cases for amounts ranging between $3,000 and $11,000.” At that price, it’s a difficult proposition to refuse, considering the costs that can rack up for legal costs. For those who just want to be done with it, the RIAA even offered a Web site, P2PLawsuits.com, where they could take care of the entire process online in a matter of minutes.

Think you can stand before a court and plead your case without any hired legal schmucks? It’s a costly gamble to make. Arizona resident Jeffrey Howell, for instance, took his chances and ended up walking away with a $40,850 fine.

Of course, not every accused file sharer crumples under foot in court. Tanya Andersen may be one of the best examples. The single mother from Portland, Oregon took the RIAA to court when they slapped her with a request for $4,000, battled for two years to clear her name, then collected over $100,000 in legal fees from the RIAA.

The Final Verdict

To be quite blunt, your chances of writing a four-digit check to the RIAA after snagging one too many Eminem albums are next to nil, especially now that the organization has backed off that strategy. And to file hoarders who amass hundreds or even thousands of pirated albums and movies, $3,000 might even look like a bargain compared to the cost of going legit and paying for them all from the beginning.

Maybe that’s why the practice of prosecuting individual consumers of pirated material has fizzled down to almost nothing, while organizations like the RIAA shift their focus to the supply side, including vendors who make thousands of peddling pirated wares.

The moral case against piracy is one we’ll leave to another day. But for pure pragmatists who steer clear of piracy on fear alone, the lesson is this: The high seas aren’t nearly as treacherous as you might think.