There’s been a temptation within the critical community to compare Alexander Bruce’s Antichamber to a certain other highly regarded first-person puzzle game from Valve Corporation. I disagree. That other game is a physics-based puzzle game at its heart, and physics – at least as we humans understand them – have no place in the universe that Antichamber occupies. Everything you do unfolds in an interconnected series of spaces that are all built on the foundation of non-Euclidean geometry.

Antichamber is a game that rewards creative thinking. It only rarely leads you along with anything as explicit as a tutorial, and even then such lessons are relegated to a sketch on a wall and an overtly simple puzzle to solve. As a player, you must constantly try to work through each given spatial riddle using the evidence laid out in front of you. Hints can be found only after a puzzle has been solved, and even then it’s typically in the form of a cryptic snatch of wisdom that only makes sense in retrospect. Comments like “Some doors will close unless we hold them open” or “There are multiple ways to approach a situation.”

The challenge only becomes more complex as you proceed and additional items are added to your toolbox. Antichamber features the unique Bit Gun which, when you first pick it up, can be used to absorb certain blocks found in the environment and spit them back out on a target of your choosing. This can be used to create platforms, bridge gaps, and the like. It’s also possible to produce more blocks out of the ones you have, once you’ve absorbed a certain amount.

Impressively, each new power variation added to your Bit Gun has a tendency to fundamentally alter the way you think about each puzzle. Antichamber evolves multiple times as you explore and discover more of its world. Much like the ever-shifting environment that surrounds you, each new tool breeds an evolved understanding of the rules of this place. In some ways, it’s as simple an equation as “new Bit Gun power = new areas to access,” but the process of figuring out how to harness this new tool to access those areas is constantly being reinvented as you progress.

Then there’s the world itself, a beautifully minimal construct that bends and shapes itself around your progress. Many corridors wind back around to previously visited spaces, but with zero semblance of architectural integrity. You might make six sharp left turns as you follow a single hallway along a seemingly circular path, only to suddenly find yourself on another part of the map that has no business being connected to the space you just exited. You may then turn around to trace your steps, only to discover that the path you took to get here is gone.

Pressing the ESC key at any time sends you back to a hub room from which any discovered location on the map is instantly accessible with a single click. You’ll quickly figure out that special icons tell you where you just came from and your point of origin following your previous hub visit, allowing you to easily reset a puzzle that you might have fouled up moments before.

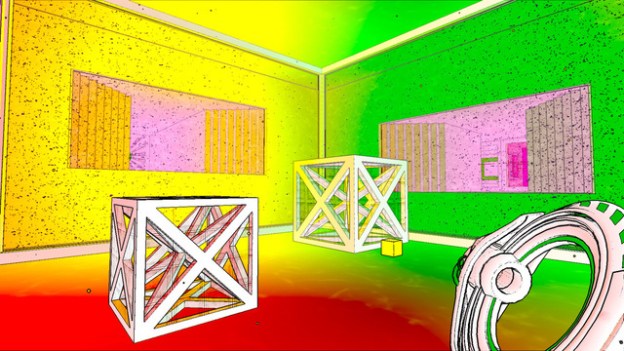

Antichamber‘s minimalist environments, all built within Unreal Engine 3, are beautiful to behold. Black lines and white floors/walls/ceilings dominate, but splashes of color help to highlight different bits of the world. As you delve deeper into Antichamber‘s puzzles, more colors start to pop out. Sometimes it means something or directs your attention in a certain way. Other times, it’s a shiny thing meant to distract you. The only constant that carries through all of the game’s environment is the surrealism of it all.

Conclusion

Some might pan Antichamber for its refusal to guide the player, but that’s missing the point. This is a game that is designed specifically to promote experimentation on the part of the player. When you’re dealing with a world that isn’t governed by hard-set physical laws, trying out different approaches until something works is really your only option. Antichamber succeeds admirably in giving players all the tools and well-concealed environmental cues that they need to work things out for themselves. Any game can give you a puzzle to solve, but Antichamber is unique in expecting you to also figure out what and where the puzzle is to begin with.

Score: 9.5 out of 10

(This game was reviewed on an Alienware X51 gaming PC equipped with an i5 processor and an NVIDIA GTX 555 GPU.)