“Dead Space (2023) feels a little redundant considering the original still holds up, but a well-executed remake still results in a standout action-horror experience.”

- Original has aged gracefully

- All weapons are now viable

- Detailed visual redesign

- Better zero-gravity segments

- Smart, subtle improvements

- Less visually legible

- Some changes don't feel additive

If the mark of a good video game remake is that it preserves the original experience and makes it feel the way it felt the first time you played it, then consider Dead Space a success … by default. That’s because the original 2008 action-horror game still feels perfectly modern to this day, even with some dated visuals and storytelling. I should know, because I just played the original for the first time one year ago. For a project like this, not stomping all over its source material’s corpse would be the franchise’s safest move.

That’s precisely the route developer Motive Studio went with in its retelling of Dead Space. Every choice it makes is in service of the original, from modernizing its few dated systems to making each weapon more viable in combat. Even when it does break from the script, it does so in a way that’s sure to trigger the Mandela Effect for fans. Several moments had me outright misremembering the 2008 version, as the developer reworked things with tweaks that feel like they were there all along. It’s so respectful that I can’t help but compare it to Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot take on Psycho when playing it, leaving me to wonder how necessary a project like this really is.

For anyone who’s yet to play one of gaming’s horror greats, the new take on Dead Space is a fairly definitive version of the experience. Its limb-carving combat and claustrophobic atmosphere still outclass its peers 15 years later, and that fact is only emphasized with some smart adjustments. If you’ve played the 2008 version to death, though, nothing here is likely to deepen your relationship with it. It’s a remake for remake’s sake.

All limbs intact

If I’m simply looking at Dead Space (2023) as its own piece rather than critiquing its effectiveness as a remake, it undoubtedly still works as a third-person horror experience. The story of Isaac Clarke, an engineer who finds himself stranded on an abandoned mining ship (the USG Ishimura) overrun with murderous necromorphs, plays like an even more grotesque homage to Aliens. It’s a compact game that balances tense jump scares with power-fantasy action. All of that holds true as Dead Space still exists as a perfectly engineered popcorn game.

Story was not the first installment’s strong suit, and that’s never been much of an issue. Dead Space spends a lot of time setting the groundwork for the franchise rather than telling a complete tale. It gives glimpses of what its version of 2508 looks like, balancing capitalist satire with searing indictments of religious cults. The new version tries to give its story a little emotional infusion by turning the once-silent Clarke into a fully voiced protagonist, but that doesn’t change much, other than breaking up some stretches of silence. It’s one area where I can feel that it came from a pre-The Last of Us world.

I don’t mean that as a knock; in fact, it’s part of Dead Space’s appeal. It has always worked as a tone piece, painting broad story strokes across a canvas it can fully splatter with blood, Jackson Pollock-style. The Ishimura is one of the great video game settings in that regard; it’s a dark labyrinth of eerie corridors that feels inescapable. That constant claustrophobia gives the adventure its power, as tight rooms and hallways turn every necromorph encounter into a fast fight-or-flight response. It’s a horror game of reflexes. When you’re prepared for anything, you’re in control. The second you get comfortable, say goodbye to your head.

Dead Space is carried by a signature combat system that still feels better than most games of its size.

There’s one particular sequence that best captures that dynamic. For a good chunk of the game, resources are abundant. I always feel like I have a deep stash of plasma cutter ammo, giving me some flexibility in battle. Then I meet my first Brute. The quadrupedal monster is a hulking beast compared to other necromorphs, and I’m left completely panicked as I struggle to fight it. I pump loads of ammo into it, but barely feel like I’m making a dent. I’ll eventually realize its weak point is on its backside, but not before burning through most of my ammo and making my next hour even more tense. That was exactly the experience I had playing the 2008 version, and it’s a testament to the core design that it played out the exact same way for me in 2023.

More than anything, Dead Space is carried by a signature combat system that still feels better than most games of its size. The core idea is that Clarke can carve off individual necromorph limbs using an array of creative weapons. That turns every battle into a puzzle where players can manage swarms of aliens by strategically cutting off their legs or freezing them with stasis powers. Others have tried to take notes from it, but few have delivered action that feels so satisfying to execute.

That’s one area where Motive Studio really understands the assignment. A lot of effort went into strengthening that combat system without throwing any of it away. Whereas the 2008 version was at its best when using the plasma cutter to carve limbs, every single weapon is made viable here. That’s because amputation is more dynamic here as players peel back layers of flesh with each shot rather than cleanly cut them off with a straight line. I had just as much fun melting down enemies with the flamethrower or blasting them away with the force gun as carving them up with the line gun, which never left my side in the original. Decisions like that make it clear how much Motive reveres the original game and only wanted to do its unsung ideas justice.

Invisible changes

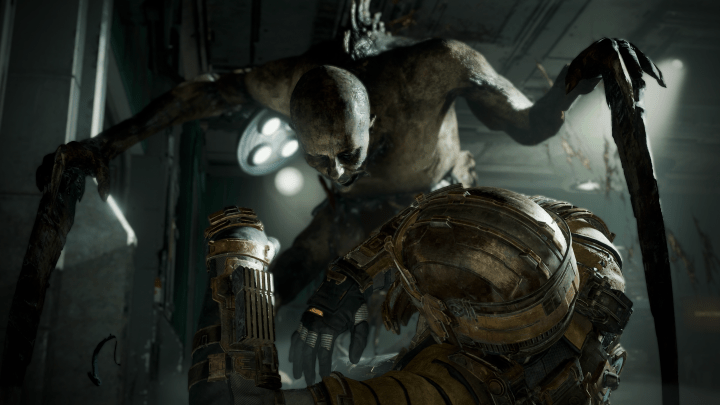

While the changes to combat stick out to me most, the Dead Space remake is loaded with tweaks. Some are more pronounced (say goodbye to that frustrating asteroid-blasting minigame), while others are as simple as reworking some story beats here and there. The most obvious change comes from its visual overhaul, which is certainly impressive. Not only does it look like a modern game, but its art direction is more detailed in general, making the Ishimura feel like more of a lived-in space.

It’s a project born from respect, as the remake helps uphold an aging game’s legacy.

Motive goes all-in on detail here. There’s much starker contrast, with darkness better hiding necromorphs. Sparks rain down from lighting fixtures in a waterfall of atmospheric light. My favorite touch is the contact beam, which now obliterates enemies in a Ghostbusters-like stream of energy that’s a bit mesmerizing. There is admittedly a downside to all those touches though, as the 2023 version is notably less legible than the original at times. In some zero-gravity battles, I’d find myself unable to locate enemies as they got lost in the ship’s details or intricate lighting. There’s a visual elegance to the 2008 version that makes it less scary, but more playable. Motive flips that dynamic here in a way that mostly ends in a net-neutral trade-off, despite the extra razzle-dazzle.

For the most part, though, the bulk of the changes are invisible. They’re the kinds of things that feel like they’ve been there all along until you play both versions side by side. For instance, zero-gravity segments have been entirely reimagined here. In the original version, Isaac couldn’t freely fly when entering a zero-gravity zone. Instead, he could only hop from surface to surface, a frustration that was addressed in Dead Space 2. The switch to free flying fits like a glove here, to the point where I’d entirely forgotten it’s not how the original operated. Other enhancements, like subtle overhauls to how weapon upgrades work, are similarly impactful without announcing themselves as flashy new features.

Motive prioritizes natural changes like that over sweeping ones, which can make the project seem a little less intricate than it really is. That’s especially true of its intensity director, a standout system that dynamically changes the state of the ship through the game. The invisible director can completely alter a room’s lighting or change what enemies spawn where, making everything feel more unpredictable. While that’s an impressive tech trick that increases its fear factor and replay potential, I’m not sure most players will actually catch its nuances on a casual playthrough.

That doesn’t mean those changes weren’t worth making. I appreciate that Motive really found a way to put its own stamp on Dead Space without altering the source material, even if you’ll need to watch a dev diary to understand it all. Every change, even story adjustments, feels tactically implemented to reinforce the original rather than overwrite it. There’s no moment where I feel like the developers are trying to one-up the former Visceral Games team. It’s a project born from respect, as the remake helps uphold an aging game’s legacy.

The question, though, is whether the original really needed that help at all.

The remake dilemma

A lot of video game remakes make total sense to me. Games are a strange art form, as everything from visuals to actual gameplay can naturally degrade as time goes by. It’s hard to communicate the importance of a game like Shadow of the Colossus to younger audiences today when its mechanics feel downright archaic by modern standards. In cases like that, a remake feels like a necessary step toward preserving a game’s importance — an issue that a movie like Casablanca will simply never run into.

But what is the ultimate goal of remaking a game like Dead Space, something that still plays well and is easily purchasable on various storefronts? While 2008 feels like a lifetime ago, it’s not that far off in video game years. Tech has slowly plateaued since the Xbox 360 days and standout games from that era often hold up. While I undoubtedly enjoyed my return to the Ishimura about as much as my first playthrough a year ago, I can’t say that it felt meaningfully different. On an emotional level, it just felt like your standard replay.

I feel the same way I do when a Hollywood studio green-lights a new film solely because it’s on the verge of losing its IP rights.

As I played, I struggled to find what made the project feel like a necessary move over making Dead Space 4 or rebooting into a new story entirely. In Sony’s controversial The Last of Us Part I, I could at least point to its deep list of accessibility options that made the original playable for people with various disabilities. While Dead Space sports its own accessibility menu, it isn’t terribly extensive, with a bulk of its options pertaining to subtitle customization (it also gives players the option to enable content warnings, which is thoroughly implemented, but also a bit funny in a game in which ultraviolent limb amputation is the core gameplay hook).

Other changes come off as superfluous. The 2008 game featured resource-filled rooms that could only be unlocked with the same high-value nodes used to upgrade weapons. It added a small bit of decision-making to exploration that fit with its survival horror resource management hook. That’s been replaced here with a somewhat arbitrary security system, where Isaac gains access to rooms and bins by gaining clearance through the story. Theoretically, that gives players a reason to backtrack, but I certainly wasn’t motivated to keep track of every closed locker along my travels. It’s a minor nitpick, but one that highlights how much I have to zoom in to play a round of spot the difference between the two games.

I cited Van Sant’s maligned Psycho remake upfront, but the more accurate comparison might be Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. Ten years after directing the psychological horror movie in 1997, Haneke would go on to remake the Austrian film in English shot-for-shot, going as far as to use the same set and props. The director would say that the film was always conceived as an American production, but that rationale doesn’t make its existence any less confusing. Why watch the remake when you could watch the perfectly comparable original? Is the second version truly additive? Does it matter which you watch?

I’m left with the same questions as I reflect on Dead Space (2023) despite unequivocally enjoying it as much as the original. At times, I feel the same way I do when a Hollywood studio green-lights a new film solely because it’s on the verge of losing its IP rights. Am I playing a Dead Space remake because someone felt the horror story would resonate more after the collective trauma brought on by a pandemic? Or am I playing it because EA leadership deemed that the franchise needed its social relevance restored if it’s going to remain a repeatable revenue source?

Though I’m all too aware of the cold, often artless reality of business, I still find value in this version of Dead Space. Its capitalist satire (ironically) stings a bit more in 2023, and its brand of inescapable isolation could hit a little closer to home for players old and new. All of that — coupled with impressive backend innovations that make Motive a studio to watch — is enough to warrant one more blood-soaked return to the USG Ishimura.

Dead Space was reviewed on a PlayStation 5 hooked up to a TCL 6-Series R635.