My nine-year-old eyes peered at the off-white “stone” cradled in my father’s hand; The Wishbringer stone, capable of granting its owner seven wishes. This physical manifestation of Infocom’s classic text adventure captured my young imagination. Previously, games to me were Pole Position and Pac-Man. Here though was a stone that could grant wishes. Wishes! It was packed right in with the game. Brian Moriarty’s clever puzzles confounded my still-developing grasp on the nuances of the English language, but the memory of holding that stone for the first time and imagining the possibilities it represented remains as potent now as it was when it happened 25 years ago.

Fast-forward to February 2013, just days before my 35th birthday. I’m sitting with Dave Lebling, Infocom founder and creator of some of the studio’s best-known hits – including The Lurking Horror, a personal favorite – on the morning after he and fellow former Imp Marc Blank were honored for their pioneering work in the games development space at the 2013 D.I.C.E. Awards. I can’t help but think back on that first encounter with Wishbringer as Lebling and I chat, even as the interview kicks off without even the faintest mention of Infocom’s place in the history books.

From Game Maker To Gamer

“The game I play the most is World of Warcraft,” Lebling says enthusiastically when asked about his current gaming habits. “I’ve been into MMOs for a long time. I was a hardcore EverQuest player; I was in a guild on one server that did all the top-end content, and I just got to the point where I did not want to devote the time. Being in a high-end raiding guild in EverQuest effectively meant that you had a second job. It was just too much. While it lasted, it was fun.”

Lebling admits to being a member of a guild, but to him WoW isn’t a social game. In his mind, the ever-popular MMORPG is largely a solo game until you get around to raiding.

“In Warcraft I stayed away from any kind of raiding,” he said. “I’m just a casual player; I’ll do everything you can do without doing raids. So I have very high-end gear for someone who doesn’t do raids.”

I mention how funny it is to hear him speak so knowledgeably about an online-focused game like WoW when Infocom offered anything but. The sort of text adventures that Lebling and his collaborators helped to popularize were developed at a time before the Internet existed as we knew it. Amazingly, the various Infocom founders still came up with ways to inject a social element into their play, even though at the time it was only in the context of local networks.

“One of the things that was interesting about MUDDLE, the language we wrote Zork in, is that it had [the ability] to send stuff back and forth [over a network]. I think it was [fellow Infocom founder Marc Blank] who actually put in a little module to listen to it,” Lebling explains.

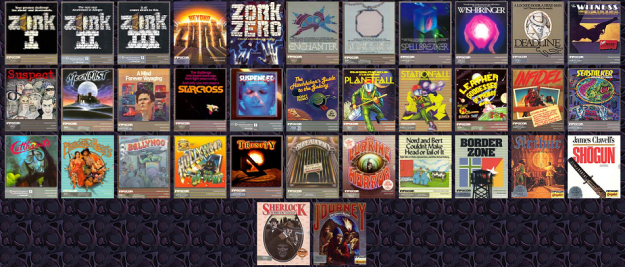

Infocom began its life in an MIT lab in 1979, when Lebling teamed with Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Tim Anderson to create their first game, Zork. That game went on to sell over one million copies. Infocom text adventures were an immediate hit in the then-young video game industry. Activision later acquired Infocom in 1986, but the transition was a difficult one. The rise of graphically reliant games on home consoles and PCs saw text adventures quickly marginalized, to the point that Activision filed a lawsuit alleging that too much had been spent on the Infocom acquisition. The studio officially shuttered in 1989, though the hard times to come weren’t a concern for the young, jokester MIT students behind Zork.

“So someone – one of us, often – could send the game a message. That message was just code, so we would execute the code remotely. This was before anyone thought anything about security. We could eavesdrop on what people were doing; that was just a feature of the operating system we had. You typed an arcane sequence of characters, and everything that came out on [the player’s] terminal came out on my terminal. The thing that was cool was that you could send code. So if you wanted to frustrate somebody, you could flip a switch and say ‘move that object there,’ so suddenly, some object [the player] was looking for would appear in the room. Late nights fooling around.”

Discovering Emergent Silliness

The first Infocom title I ever really fell in love with was Steve Meretzky’s “serious” game, A Mind Forever Voyaging. You play as an artificial intelligence that is capable of jumping into a person’s life at various points in a simulated future. My young mind couldn’t quite grasp everything that was going on, but Meretzky painted a memorable world using nothing more than words. The quirky use of language that Infocom games were founded upon (and that helped to make them such memorable experiences) were, as Lebling tells me, very much a product of the time.

“That was the thing that we, in some sense, became famous for: the emergent silliness. Sometimes it wasn’t emergent, it was right there from the beginning.”

Lebling chuckles as he thinks back on the endlessly entertaining challenge that programming in MUDDLE presented. “So it would [interpret a ‘dig’ command], quite logically I guess, as ‘dig with hands.’ The response when you weren’t digging with the right thing was, ‘Digging with the [thing you were trying to dig with] is slow and tedious.’ So it read, ‘Digging with the hands is slow and tedious.’ It’s kind of a bad joke, but everybody cracked up at it. So we kept it in even though we could have changed it to say something… specific for hands.

“That was the thing that we, in some sense, became famous for: the emergent silliness. Sometimes it wasn’t emergent, it was right there from the beginning.”

Feelies With Feeling

Lebling smiles when I mention my lingering fondness for the feelies. “Deadline was the first game to have feelies. It was a detective story. If you’re a fan of mystery and detective stories, you know there’s always a lot of background and exposition. It just goes on for page after page in a book, but we didn’t have the space for that stuff.” It’s a pretty sharp solution to the problem of limiting how much information can be conveyed to the player. Provide that info on printed materials, and make those materials relevant to the game.

“The other thing is that [fellow Infocom founder Marc Blank] had discovered reprints of the original games with feelies, which were written by a gentleman named Dennis Wheatley back in the 1930s. The way the worked is, there was a… detective story, just a normal narrative, but there were also things that contributed to it. Dossiers, interviews… I think the first one actually had locks of hair.”

Lebling explains how the interactive Wheatley mysteries went out of print for decades before being revived back in the ’70s. Blank discovered and immediately fell in love with the first one, and he had no problem sharing that enthusiasm to his fellow Infocom Imps, all of whom were already keyed up about the potential of interactive entertainment. When Deadline was being polished off, it turned out to be a perfect fit for the sort of bonus content that Blank discovered in Wheatley’s work. Thus, the Deadline dossier packaging was born.

A more organic approach to copy protection also grew out of feelies, with some of the in-box content required in order to solve certain in-game puzzles. It was a sensible approach at a time when things like online checks weren’t possible, but as Lebling tells me it really boiled down to a matter of convenience. “We thought that the on-disc copy protection that games tended to have back then was just an enormous pain. If I remember correctly, it was particularly bad on the Apple II because the old Apple II DOS was just weird. You had to essentially write… your own disc format. It was just awful.

“We used to joke that we never sold more than one copy of a game in Italy, and that was enough.”

Inspiring A New Generation

Of course, none of this is a concern for Lebling anymore; the Infocom founder still works with computers, but games have become more of a hobby than a pursuit. He currently works as a programmer for British defense and aerospace company, BAE Systems. He admits to having an interest in trying out The Walking Dead, Journey, and a handful of others, but the D.I.C.E. honor didn’t fire up any of the old urges that led to Infocom’s creation. Lebling still treasures the creatively fertile period of his life that he spent at the company, and he cherished the recognition, however momentary, that the D.I.C.E. Awards delivered on.

It’s 1987 all over again and I’m standing next to my dad as he introduces me to Wishbringer‘s town of Festeron. The small, plastic pebble is now gripped tightly in my hand, and I wish more than anything that I could have even a momentary glimpse of the reality behind this fascinating little virtual world. More than two decades later, my wish was granted. Thank you to Dave, Marc, Steve, and their ceaselessly creative collaborators who took the all-important first stumbling steps toward granting that wish for a world of future gamers.