In 1983, Nintendo faced a make-or-break moment.

Its first video game system, the Famicom, had just launched in Japan and plans were in motion to bring it to American audiences next. But the move from arcade cabinets into living rooms required a delicate marketing operation. Nintendo of America needed to convince Western audiences that coin-op games were experiences worth owning, rather than special attractions meant to be caged away in arcades like animals in a petting zoo.

To accomplish that feat, the emerging video game giant did something unimaginable by the notoriously tight restrictions it maintains today: It licensed out its biggest mascots to third-party companies and gave them free rein. Long before they were the manicured household names we know today, characters like Mario popped up on everything from merchandise to animated shows — very few of which Nintendo had much involvement in.

From this cavalier attitude came the first ever Mario adaptation outside of video games: Donkey Kong Goes Home, the first time Mario would ever speak.

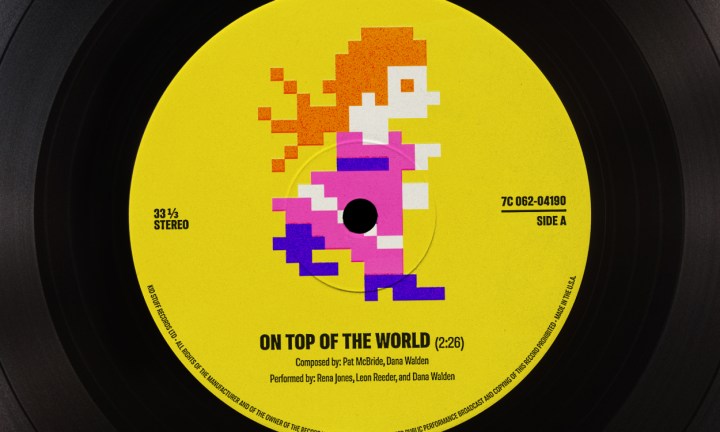

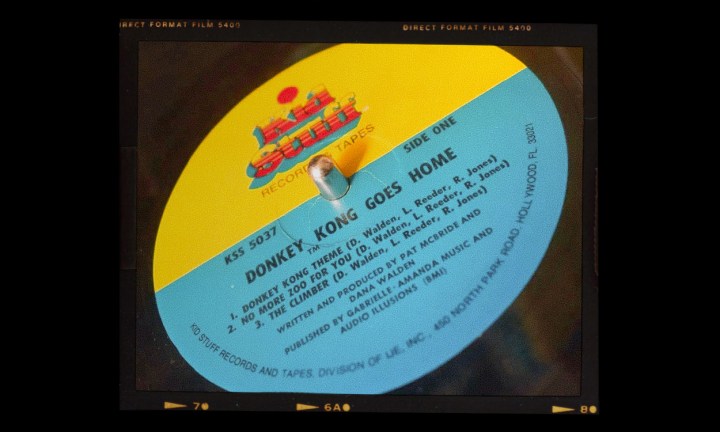

Released on vinyl in 1983 under the now-defunct Kid Stuff Records label, Donkey Kong Goes Home is a long-forgotten children’s music album. It’s an oddball odyssey that plays out like a 20-minute musical, flipping between ‘80s grooves and spoken word interludes that are such a far cry from the games that they may as well be from another planet. The album serves as a full narrative adaptation of 1981’s Donkey Kong, giving the ape a backstory, explaining how he comes to scale a construction site, and reimagining its damsel-in-distress Pauline as a friendly pizza delivery girl. Most significant of all, though, is that it featured a fully voiced Mario almost a decade before Charles Martinet would step into the character’s iconic overalls.

It’s a critical piece of Mario history, but you wouldn’t know that from reading Nintendo’s own lore, fan forums, or even Wikipedia. Donkey Kong Goes Home exists in a state of fossilization today, with nearly no digital footprint in the internet age or preservation efforts from Nintendo. You can only hear it through a few YouTube uploads that have racked up less than 10,000 views apiece. The only way you’d be able to learn anything more about the decades-old project would be by tracking down the guys behind the disembodied voices that gave life to these characters for the first time. And I was curious enough about its puzzling creation to do exactly that.

Through a series of interviews with the musicians behind Donkey Kong Goes Home, I’d unearth the lost history behind a pioneering piece of Mario media. And it was underneath decades of dust that I’d come face to face with the original Mario.

The climber

The full story of how Donkey Kong Goes Home came to be is a surprisingly complicated chain of events that includes a 1980s hit single, a failed Blockbuster video game initiative, and Vincent Price. The heart of the tale is much easier to follow: It was the product of two bored musicians looking for new challenges in their careers at the same time.

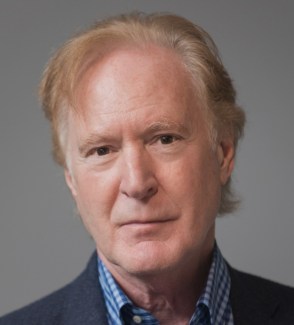

The first key player is Pat McBride, then a young musician in Chicago who was a member of the 1960s band New Colony Six. While they were usually more of a supporting act for bands like The Beach Boys and the Yardbirds, New Colony Six found modest success with two Top 20 records and were credited at the time for creating the “garage band sound” (“It was just because we weren’t that good,” McBride jokes.) But as the band’s sound changed over time and moved into ballad territory, McBride began to lose interest and would eventually part ways with the group.

His pursuit of a new creative outlet took him on an eclectic career adventure. He’d write for the era’s most popular horror magazines, design sound for a haunted house ride in one of the world’s first indoor amusement parks, work with Vincent Price on a series of commercials for the project, and help Blockbuster break into the video game industry with a project called Blockbuster Adventure that never saw the light of day.

“All of a sudden, I had this reputation of being a designer of entertainment attractions. And I knew nothing!” McBride tells Digital Trends.

With a string of high-profile projects to his name, McBride’s increased publicity drew the attention of Kid Stuff Records, which was one of the major players in the lucrative children’s music industry at the time right alongside mega-corporations like Disney. The company wanted to court McBride to produce some albums, and he was interested in the challenge. To do that, though, he’d need the right creative partner. Enter Dana Walden.

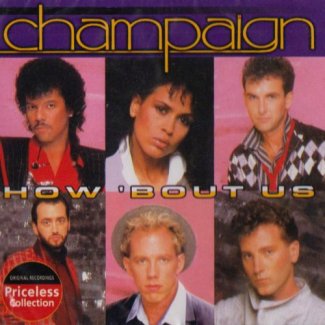

Like McBride, Walden was a musician — a keyboardist for the R&B band Champaign. The two met at a gig and hit it off immediately. When Champaign scored a hit in 1981 with the song How ‘Bout Us, it turned out to be a double-edged sword for Walden, who quickly grew tired of the pressure that came with striking gold. He wanted a change, and McBride would offer one at exactly the right moment. He floated the idea of collaborating on some kid’s albums, and Walden was happy to come aboard.

“This is a strange thing to admit, but I was kind of bored with doing what I was doing,” Walden tells Digital Trends. “Music is a freedom from the outside, and everybody goes ‘Wow what a cool life!’ But once you get a hit, you have to start recreating what you did. Just to have more fun, we had the opportunity to do this children’s music, and I was having more fun doing that than I was in the real music business that was making a lot of money.”

On top of the world

Walden and McBride formed a recording group that included two other members of Champaign: Rena Jones and Leon Reeder. McBride’s wide range of connections soon netted work from unexpected places. As part of his foray into entertainment design, he’d done work with Bally on a pinball game called The Machine. Though the project ended up canceled, the relationship still turned out to be valuable, as Bally happened to own the rights to Pac-Man at the time. The ever-persuasive McBride was able to secure the rights to the intellectual property for Kid Stuff and start producing Pac-Man albums.

On records like The Pac-Man Album and The Amazing Adventures of Pac-Man, the team built out a winning formula by taking the source material and running with it. Rather than just putting out a loose collection of silly songs vaguely themed around the game, they’d feature spoken word interludes that would tell a full story. The albums are essentially micro video game musicals that take a lot of artistic liberties, which was ambitious for children’s music of the era.

The team’s Pac-Man Christmas Album, for instance, tells the story of the game’s ghosts planning to sneak attack Pac-Man during his holiday party, but instead finding themselves moved by the spirit of Christmas. All of that plays out between full pop songs like An Old Fashioned Christmas, which are a great deal more complex than The Wheels on the Bus.

“Who buys this stuff? The parents,” Walden explains. “And as a parent, there was a lot of children’s music that I would have for my kids around the house that would drive me crazy. I absolutely hated it! So I wanted to do something that parents could fall in love with. And still find that place where you can dream up any kind of song and incorporate a childlike innocence to it.”

All they knew was that there was a giant ape, a construction site, a kidnapped woman, and an Italian plumber who could jump.

The quartet’s success with Pac-Man led to an even bigger opportunity when Kid Stuff Records secured the rights to an important game: Donkey Kong. They didn’t know it at the time, but they were wading in at one of the most important eras in Nintendo’s history. In 1982, it had just launched a sequel to the arcade hit, Donkey Kong Jr., which brought one crucial change, changing its hero’s name from Jumpman to Mario. That meant Kid Stuff would create the first true Mario adaptation ever in 1983. McBride and Walden were entrusted with that honor — and they had almost nothing to work with.

Despite Donkey Kong being a smash hit, there wasn’t a wealth of canonical lore to build off of. All they knew was that there was a giant ape, a construction site, a kidnapped woman, and an Italian plumber who could jump. What made the task even more challenging was that the team would never hear a single word from Nintendo; they’d never speak to the company or receive a single note during the process.

It was up to them to transform a simple arcade game into a grand musical — and they’d be able to get away with just about anything.

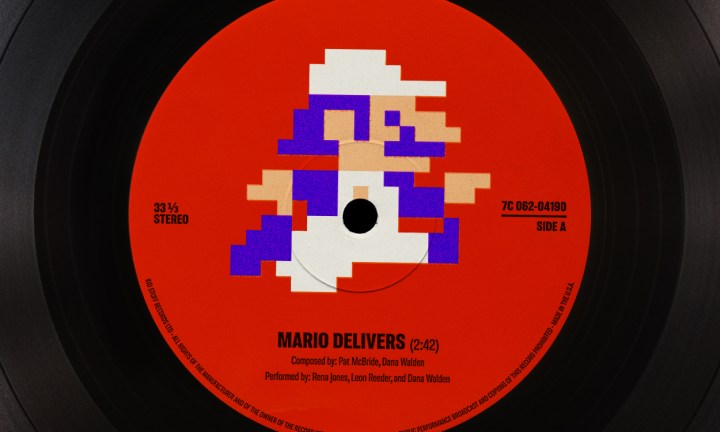

Mario delivers

The team spent just a few short months planning out what would become Donkey Kong Goes Home. To bring it to life, they’d need to fill in a lot of gaps left by the game to form a cohesive narrative. Because of that, the album takes so much creative license with the characters that it’s almost a little shocking listening to it in the context of today’s Nintendo.

The story takes place in the town of “Gamesville” on the day that a traveling circus has come to town — and Donkey Kong is its main attraction. Since the ape can’t talk, a good deal of the story comes from an onlooker voiced by Rena Jones. She explains that Donkey Kong used to happily live in a zoo in Gamesville, where a woman named Pauline would bring him lunch. Unfortunately, his zoo was torn down and replaced with a construction project. Donkey Kong breaks out of the circus in a moment of homesickness, yearning to escape his captivity and return to, well, a different form of captivity, I suppose.

Elsewhere in town, we meet Mario, who runs a pizza shop. After getting an order from “Jake the Watchman” at the construction site, Mario sends out his employee Pauline to deliver it. She gets to the construction site just in time to be playfully snatched up by her friend Donkey Kong, forcing Mario to jump into action. The story goes out of its way to exonerate the ape of any crimes by chalking it all up to a misunderstanding (“Donkey Kong thinks Mario is wanting to play catch,” the narrator explains as he throws oil barrels down on the hero).

It’s quite the extrapolation of the arcade game, but there’s one aspect of it that’s particularly shocking: Mario appears as a fully-voiced character on the album. Considering how close the record was to Jumpman’s name change, that makes it the first time the character ever spoke, period. During our chat, I asked McBride if he remembered who had the honor of bringing Mario to life for the first time.

“I do, because it was me,” he replied.

You can hear McBride ad-libbing “wahoos!” that sound almost identical to the ones used in the games today.

Adding to his already long resume by the early 80s, McBride had done a fair amount of voice acting. He most notably played the role of a Keebler elf in a classic cookie jingle (“Well you never will believe where those Keebler Cookies come from …”). McBride was also the voice of Pac-Man on the team’s earlier albums, recording his wobbly cartoon voice through a tin coffee can. Nintendo never gave the team a word of guidance regarding what Mario should sound like, so McBride had to improvise. The result is a joyfully absurd Italian accent created out of the little details the team had on the character.

“He was Mario, he had that Italian background, we knew what his occupation was, and we knew he was a really good guy,” McBride says when describing his process for crafting the voice on the fly during recording. “In my brain, if there were kids in the neighborhood, he’d always pat them on the head and say hi. He’d look out for everyone, so he became the real good guy.”

What’s surprising is that McBride’s voice isn’t actually that far off from what Mario sounds like today. It’s a more exaggerated version of Charles Martinet’s popular iteration, but listen closely and you’ll hear that McBride was actually far ahead of his time. In the penultimate song Mario delivers, you can hear him ad-libbing “wahoos!” that sound almost identical to the ones used in the games today. Though we may never know how Nintendo executives reacted to the performance, it does appear that McBride left some kind of mark on the series. He’s a lost ancestor at the top of the family tree, a significant feat that was only possible due to Nintendo simply not caring about what would become its most important property.

“You would think that we would have some rules to follow. We didn’t have one single rule,” Walden says. “No one told us that the brand was this, you have to do this, it needs to sound like this. Nothing! That’s pretty hilarious and amazing. Pat doing the voice of Mario as some kind of Italian guy, you’d think someone would have gone ‘Well, maybe, but here’s how we want it done’ … but we had free reign, which is a dream. That’s not going to happen now.”

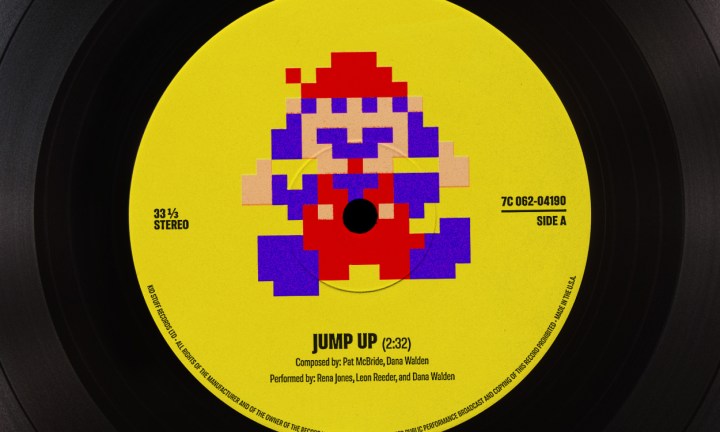

Jump up

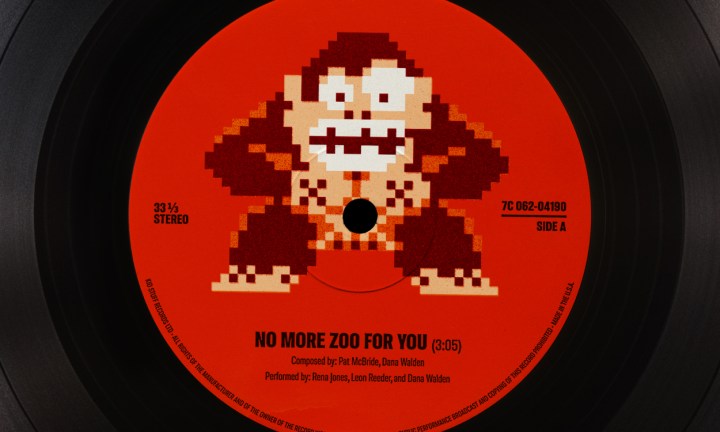

The freedom Walden speaks of extends to the actual music on the record, which is largely unlike anything you might expect from a children’s album. It starts typically enough with a silly Donkey Kong theme that almost plays like an early iteration of the DK Rap (“We’re talking gorilla, we’re not talking Godzilla!”). The compositions get significantly more complex as it progresses though. No More Zoo For You is a mid-tempo ballad filled with breezy harmonies, while The Climber is a prog rock epic that almost sounds like it’s riffing on Styx.

“When you hear the complexity of the background vocals or the composition, it’s because that was our background,” McBride says. “We took what we were doing in rock and roll and pop, and we were transferring that into a kid’s medium knowing we were breaking every single rule there was. That was also the time of Michael Jackson. Kids were buying kid’s records, but when Michael Jackson came along, those same kids were buying Michael Jackson. So we knew there was a transition that was taking place.”

The lyrical content is more literal, with McBride saying that each was written around a physical attribute of the game. Jump Up, for instance, turns Mario’s signature move into a high-energy pop anthem. Interestingly enough, the title would be reused in Super Mario Odyssey for its original song Jump Up, Super Star!, leaving more room to wonder whether or not Nintendo secretly reveres the record.

Considering how high profile a client Nintendo was at the time, one might assume that projects like this were a reliable cash cow for two musicians who had struggled through the unpredictable hit-making grind. Pump out some mindless kid’s music with minimal effort, get a paycheck. That wasn’t the case.

“Believe me, we weren’t making any money doing this stuff!” McBride says. “The only reason we kept doing this was because we were having a good time. Since Dana had his studio, it wasn’t costing us, but if we were paying studio hours, we would have lost a fortune by doing this!”

“The record company didn’t give a shit.”

The whole suite of songs was recorded in a single week in Walden’s own studio, a series of sessions McBride and Walden both look back on fondly. Both men describe the sessions as incredibly fun, noting that the lack of oversight let them execute their exact, ambitious vision for a Donkey Kong album. It was a refreshing experience for two people who had struggled with the high stakes of the traditional music industry and the pressure to produce hits. They were left with a tight, 20-minute kid’s album that they felt even parents would love and were proud to present to Kid Stuff Records.

The reception wasn’t exactly what they were hoping for.

“It was a very disappointing day,” McBride says. “We went to Kids Stuff Records, we had produced Donkey Kong, we were proud of it. We played it for one of the execs there and he looked at us and said ‘You know, I hate to break your bubble, but no one cares about the music that’s inside. They buy it based on the cover and maybe the name.’”

“The record company didn’t give a shit,” Walden says with a laugh.

No more zoo for you

Donkey Kong Goes Home launched to a warm public reception at the time, but the lack of corporate enthusiasm for their product — or even any feedback — left them deflated. Nintendo didn’t have anything to say once the album was submitted. “Just nothing,” says McBride. “Not great. Not bad. I’m sure they were just on to the next thing.”

That sobering reality of how the business functioned ultimately dampened the team’s enthusiasm. Kid Stuff asked McBride to join them as they looked to push into gaming with a line of TV game show cartridges, but that would require him to give up his own design company and commit to Kid Stuff full-time. He had no interest in being locked into another project and turned them down as a result. That decision ended the team’s relationship with the company after a few short years of working on albums. The company did launch the cartridges but went bankrupt seven or eight years later as it struggled with distribution.

There’s a running theme throughout my conversation with McBride, as he continually has to explain projects that have been completely lost to time. There’s no record of Blockbuster Adventure online, and I had to pull teeth to get any information about Donkey Kong Goes Home. The latter is especially surprising considering the album’s historical importance. You’d think that its position as the first true Mario adaptation would earn it some reverence — especially in a year featuring an incredibly successful Mario film — but Nintendo of America has all but buried that piece of Mario history.

“Look, pioneers get shot in the back a lot,” McBride notes.

“It’s a little disappointing. We tried to be very innovative in the things we approached. And because of that, entrepreneurs would come to us. With so many things, if they don’t go out there and make a bit of a splash, the information just disappears — especially if it happened before the internet became so vibrant. Those eras are really gone. Even when I look at Wikipedia, I realize how wrong or incomplete it is.”

At the start of this story, I mentioned that 1983 was a crucial year for Nintendo. That became doubly true when the video game market famously crashed that very same year, something Nintendo attributed to an oversaturation of low-quality games on Atari’s consoles. To revive the industry, Nintendo got much stricter about licensing and introduced the Nintendo Seal of Quality for its games. By 1986, that proved to be a financially viable strategy that led to a sudden tightening of the company’s carefree attitude toward third-party companies handling its IP. The creative conditions that allowed Walden and McBride to create a work they were proud of disappeared, leading to the notoriously protective version of the company we know today.

“We had free rein, which is a dream. That’s not going to happen now.”

Though it’s nearly been lost to time, Donkey Kong Goes Home stands tall as a relic from a much looser video game industry that doesn’t exist today. It’s a testament to what artists can create out of a brand’s building blocks without committees, CEOs, and lawyers peering over their shoulders. To a casual listener, it’s just a silly children’s album. But for Walden and McBride, it was a moment of creative freedom that has only become more distant in our current corporate landscape.

Both musicians look back on the project with pride to this day, blown away by the weird and wonderful thing they were able to create 30 years ago. And when the duo revisited the album together during this article’s reporting, their ambitious attitudes immediately sprang back to life.

“If nothing else, I’m afraid that because I listened to it, I’m going to want to sit with Pat and dream up a Broadway-style musical,” Walden says. “That would be a licensing nightmare, but who knows!”