It’s best to walk into Kentucky Route Zero with no knowledge of what you’re about to experience. It’s more fun that way. In fact, you should stop reading right now and go do that if you haven’t. The game defies convention and refuses categorization, resembling an adventure game but playing more like a Choose Your Own Adventure. It’s delightfully odd and sort of unsettling, but it’s presented in a way that is difficult to really pin down.

It’s best to walk into Kentucky Route Zero with no knowledge of what you’re about to experience. It’s more fun that way. In fact, you should stop reading right now and go do that if you haven’t. The game defies convention and refuses categorization, resembling an adventure game but playing more like a Choose Your Own Adventure. It’s delightfully odd and sort of unsettling, but it’s presented in a way that is difficult to really pin down.

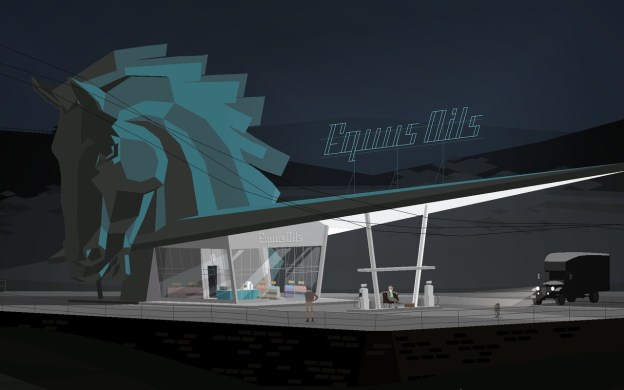

It’s all the work of the two-man development team that makes up Cardboard Computer, Jake Elliott and Tamas Kemenczy. KR0 was inspired in part by their shared love of theater, as Elliott told Digital Trends during a recent interview. “That [influence] shows up in the art direction; it’s inspired a lot by theatrical set designs. Also, the play mechanics are more about the player being a performer instead of a puzzle-solver or something like that.”

Kentucky Route Zero resembles a point-and-click adventure game, but it quickly becomes clear after you start playing that the principal focus isn’t on solving puzzles, but rather allowing players to author their own story. You might be faced with a locked computer and given a hint that the password is the text of a poem. What you won’t initially realize as you make selections from a series of text prompts that follow, is that you’ll get into the computer no matter what. This is a game that asks you to invest in your own journey as it unfolds rather than reach constantly for the next shiny, brass ring.

“This being a game set in the South, we were looking at a lot of Southern gothic fiction. Stuff like Tennessee Williams,” Elliott explained. “We were reading those plays and considering how to make a game that responded to some of those same ideas. This theatrical idea, with the player being a performer- there’s moments where you can make some decisions about the character’s inner life rather than the actions that they’re doing. That’s akin to a performer in a play having to consider making up a backstory for their character in order to perform authentically.”

There’s actually a fairly simple and straightforward reason that this seeming adventure game skips the expected focus on puzzles: it’s not something that Elliott and Kemenczy really excel at. “There was one puzzle that was in the game for a very long time that we kept re-working and ended up just cutting,” Elliott revealed. “I guess a lot of games that we play don’t really have a challenge built into them. Some of the more experimental interactive fiction stuff.”

During our chat, Elliott cites a number of titles – familiar and unfamiliar – that he and his fellow programmer draw inspiration from. Everything from Adam Cadre’s Phototopia to the collected works of Sierra On-Line and Infocom, to the ever-growing presence of Twine-based text adventures. Twine is, as Elliott describes it, a “hypertext game engine” that aims to offer an accessible development platform to those who don’t know how to code.

“It’s been really great because it’s very accessible to people who… don’t have a programming background,” he said. “People who are comfortable writing, that’s pretty much all they need to make games in Twine. So there’s a lot of new voices. That’s something that we’re really immersed in. The little text adventure moments in the overworld map [in Kentucky Route Zero], those are kind of inspired by our experiences playing those Twine games.”

“The point-and-click adventure interface we just sort of arrived at,” Elliott added. “We never pushed the game as though it were going to be an adventure game. The interface just fell into place for us, and it’s interesting to see how much that sort of guides people’s expectations about what’s going to happen.”

Expectations are shattered from moment one, with the game loading directly to the start of play with no main menu or credit sequence or anything of the sort. It ends in a similar fashion, with a text screen that reads “End of Act One.” Even that wasn’t there to start with; originally, players who completed episode one were simply dropped back to their computer desktop.

“If you download the [post-release] update, it actually says ‘End of Act One’ at the end, just because we got so many emails from people that said it was crashing,” Elliot explained, chuckling. “It was an experiment. We kept thinking about what the main menu should look like and didn’t really have any ideas, so we just decided not to include it. It’s just Tamas and I [working on Kentucky Route Zero], and we’re putting a lot of time into the parts of it that we care about and just trying not to do the other parts.”

“I guess that’s also related to this decision to skip puzzles; really trying to stay focused on what we think we can do well within this game. So some things like menu design or end credits, it’s just kind of an experiment to leave those out. I like that the game starts right away when you open it and it ends right away when you’re done playing. A title screen or a main menu or a credit sequence in a game can act as a sort of antechamber between the experience and you looking at your desktop. I like that it doesn’t give you the chance to pause and prepare yourself to play.”

It’s best to simply let the game wash over you. The presentation of the story is rooted in magical realism, a genre in which fantastical things happen that are regarded as normal by the residents of that world. “Magical realist writing is also very political,” Elliott added. “[People like] Salman Rushdie use magical realism as a way to treat some really serious issues about the way that marginalized people are oppressed. So they were able to treat these really serious issues in a playful but respectful way by using this blend of realism and fantasy. That’s what we were trying to do with working class people from the South during some nameless recession.”

Kentucky Route Zero initially grew out of a successful Kickstarter bid, with the two-man Cardboard Computer team receiving $8,000 from backers, allowing them to license the necessary software and pay the musicians that provided the game’s soundtrack. Elliott acknowledges the value of the cash infusion, but the Kickstarter success was valuable for other reasons as well. “It was really great to start building an audience there,” he said. “We got a couple hundred people who stated that they believed in the project and we’ve been in close contact with them throughout the process. So that was really valuable, to start to discover an audience there.”

That said, Elliott hesitates when asked if he would ever commit to another Kickstarter bid. He and Kemenczy would go in a second time with the benefit of experience, knowing how to account for development schedules and the labor involved in sending out rewards, but he doesn’t necessarily see much value in going the crowdfunding route again. “It seems like the landscape is so different now. I’m really not sure it would work,” Elliott explained.

“Games now on Kickstarter usually go for quite a lot more money than we went for. I’m not really sure I would feel comfortable raising that much money on Kickstarter and I’m not really sure we would need to do another one for [the amount that we did]. Maybe there’s other ways to grow our audience now. It certainly seems that projects are higher-profile and seeking larger dollar amounts than they used to be, though there are still some cool, weird, fringe-y projects that are happening there.”

For now, the main focus for Cardboard Computer is getting out the rest of Kentucky Route Zero. There will be five episodes when all is said and done, and with the first episode out the door it’s easier for Elliott to consider what the release schedule might look like. “We are thinking about three months each for the rest of the episodes. We’re really trying to get them all done by January 2014. That’s a lot easier for us to approach and think about now that we’ve spent a lot of time working out a workflow for building the game. I think this time we do have a good sense of how long it’s going to take. We’re not committing to any dates yet, but roughly a year.”

If you’d like to hear more about Kentucky Route Zero, take a peek at my hourlong discussion of the game with colleagues Rob Manuel, Scott Nichols, and Christopher Floyd.