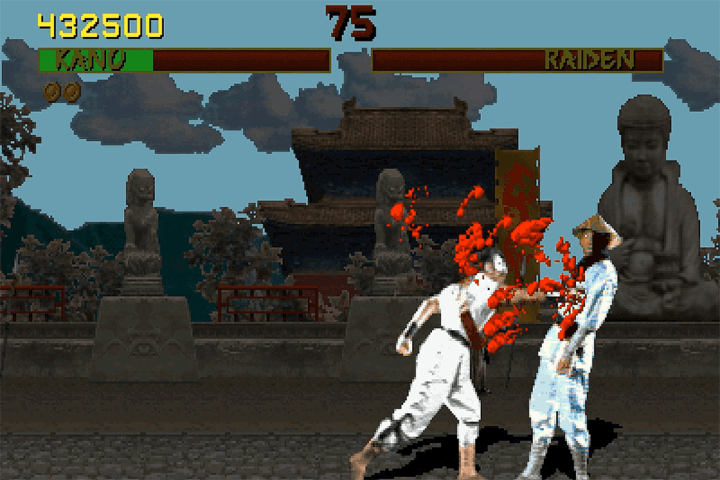

Back in the early 90s, however, the original Mortal Kombat‘s gore was unheard of in games. It made such a splash that it became embroiled in a video-game violence scandal involving senate hearings, the Sega-Nintendo rivalry, and Captain Kangaroo. Mortal Kombat became public enemy number one for the conservative crusaders arguing that violent video games would destroy America’s youth. The ensuing scuffle only served to secure Mortal Kombat‘s place as one of the most iconic games of its time, and resulted in the creation of the ESRB rating system that still governs the North American video-game industry today.

Finish him!

Mortal Kombat was born in 1991 when artist John Tobias and programmer Ed Boon, two employees at the arcade-game developer Midway, were tasked with creating an answer to Street Fighter II, which had just been released in arcades to immense acclaim. In order to set MK apart from Capcom’s iconic fighter, Tobias hit on the idea of using digitized footage of real-life actors as the basis for the character’s sprites. The technique had already been used to good effect in a number of arcade titles, such as Narc and Pit-Fighter. Actors were dressed up, filmed and then, with a bit of touch-up, imported into the game. The resulting graphics were considered at the time to be some of the most realistic visuals ever in a video game.

Graphics aside, the gameplay cleaved closely to Street Fighter‘s. Two combatants would face off on a two-dimensional plane in tactical brawls, with unique sets of special moves and combos to master for each character. It wasn’t until playtesting that Tobias and Boon hit on the innovation that would come to define the franchise. “There was an anti-climactic moment at the end that created the opportunity to do something cool,” Tobias explained in Tristan Donovan’s 2010 book, Replay: The History of Video Games. “We wanted to put a big exclamation point at the end by letting the winner really rub his victory in the face of the loser. Once we saw the player reaction, the fact that they enjoyed it and were having fun, we knew it was a good idea.”

That “exclamation point,” of course, was the fatality, an over-the-top, secret finishing move that players could use to to give their foe a flashy execution at the end of the match. In the original game, each character had one fatality, ranging from Raiden shocking his opponent with lightning until their head exploded to Kano ripping out his foe’s still-beating heart. The fatalities proved to be immensely popular, helping Mortal Kombat become a blockbuster hit for arcades where players eagerly competed for the chance to brutalize one another. Given the game’s immediate success in arcades, it was only a matter of time before it would be ported to home consoles.

“Buy me Bonestorm or go to Hell!”

Acclaim Entertainment took on the task of adapting Midway’s arcade version for the dominant home consoles of the time: the Sega Genesis and Super NES. Sega, as part of its attempt to reach teenage and adult gamers, approved the game along with all of the arcade version’s violence. Nintendo, on the other hand, held much stricter content policies, maintaining that its products were primarily for children. Accordingly, Nintendo executives insisted that Mortal Kombat‘s gore be toned down substantially for the SNES, including removing the fatalities entirely. Despite Acclaim’s insistence that the fatalities were one of the game’s main selling points, Nintendo held firm, and eventually a censored version of the game was developed for the platform. Nintendo paid for its prudishness when the more violent Genesis version went on to outsell its SNES counterpart five times over.

Released on September 13, 1993, Mortal Kombat was one of the biggest video-game launches to date. Acclaim spent a whopping $10 million on TV advertising to promote the release on “Mortal Monday.” Children and teenagers across the country asked their parents for the game, which was parodied in a Simpsons episode a few years later as Bonestorm (above). Among these children was the nine-year-old son of the chief of staff for Joe Lieberman, a Democratic senator from Connecticut (and eventual Presidential hopeful) who was utterly horrified at the extreme violence he believed to be marketed at children. Lieberman called the video-game industry to task with a senate hearing in 1993.

Flawless victory

In the week prior to the hearings, Senator Lieberman held a press conference to condemn violent video games with Captain Kangaroo, a popular children’s TV host from the 50s through the mid-80s. That Lieberman chose Captain Kangaroo rather than a more contemporary figure like Mr. Rogers perhaps speaks to how out of touch he was with the entertainment industry he was attempting to punish. Video games had grown up considerably over the course of the 80s, as did many of their earliest fans, who were increasingly interested in games with more mature subject matter.

Under mounting political pressure, rivals Sega and Nintendo met to hash out a strategy for the impending hearings. Sega advocated for an age-based rating system like films had, which would allow them to continue producing violent games. Nintendo saw little need for outside regulation, however, because of its own family-friendly ethos internally dictating what could and could not be published for its console. At the debate’s heart was the question of whom video games were for. Nintendo held the more conservative position that games were for children, while Sega recognized the growing number of older gamers and the possibility of games catering to a wider range of tastes and ages. To the bewilderment of Lieberman, executives from both companies took potshots at one another during the hearings.

Related: Mortal Kombat X review

Although the video-game industry was raked over the coals for being violent and sexist, evidence about the relationship between video game violence and real-world behavior was inconclusive. A three-month recess was called for the industry to implement a rating system. In that time, the industry’s leading publishers left the Software Publishers Association and formed their own Interactive Digital Software Association to have a stronger lobbying presence in Washington. They also formed the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) to manage the new industry-wide age rating system, which sufficiently placated the Senate to defuse the threat of a state-run regulator or an outright ban on violence.

Confident in the new rating system, Nintendo relaxed its content policies and let Mortal Kombat II come to the SNES unchanged. With its new ‘M’ rating, the developers were safe to freely promote subsequent games in the series without fear of accusations that they were intentionally corrupting children. Although Lieberman set out to limit violence in video games, the net result of the hearings was to actually make it safer to develop games with adult content such as sex and violence. Whoops.