After a decade of perfecting the narrative-driven, action-adventure formula, PlayStation’s first-party games are tackling a new genre: the roguelike. Both God of War Ragnarök and the recently released The Last of Us Part II Remastered have their own roguelike modes that remix the core combat of their respective games into a repeatable action premise. At a quick glance, they’re very similar. Both modes have players cutting through arenas filled with enemies and grabbing new upgrades en route to a final boss battle.

And yet, they couldn’t be further apart in quality.

While God of War Ragnarok: Valhalla is a standout piece of DLC that deepens Kratos’ character arc, The Last of Us Part 2’s No Return mode is a surface-level engagement farm that’s entirely at odds with the game it’s attached to. It’s a stark contrast, but one that provides a valuable teaching moment. It’s a clear example of why “fun” isn’t the only metric that’s important in making an entertaining or otherwise engaging video game; sometimes it’s just as important to move players’ brains as much as their fingers.

No thought

If you’re coming to No Return looking for the same attention paid to nuanced storytelling that’s made The Last of Us such a mainstream phenomenon, you’ll be sorely disappointed. The slim roguelike mode doesn’t have any narrative throughline to speak of and doesn’t aim to be consistent with The Last of Us Part II. It’s pure action, meant only to test players who have built up their skills in the three and a half years since the base game’s release.

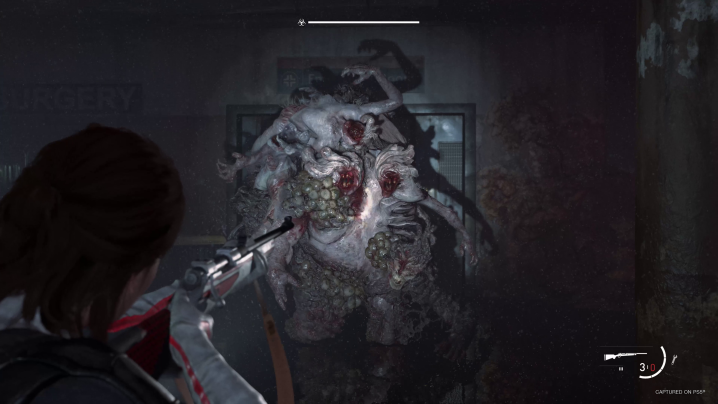

It’s light entertainment, though players are sure to be split on how “fun” it actually is. No Return isn’t exactly custom-built as a standalone mode. Instead, it heavily reuses assets and systems from The Last of Us Part II. Familiar environments and enemies are remixed into short combat encounters where players blast through six arenas leading to a tough boss fight. More crucially, though, is that the action still feels as raw as it does in the story. The animations are brutally detailed and enemies still scream out in agony for their killed companions.

All of these ideas were effective in The Last of Us Part II, if not a little overwrought, because they were built in tandem with the story. The base game tells a two-sided revenge story in which both Ellie and Abby blindly tear one another apart. Both characters think they’re justified in their actions, killing hundreds of goons on their “righteous” missions. In reality, neither character is a hero. Both are trapped in a destructive cycle of violence that dehumanizes everyone around them. Ideas like enemies calling out to dead companions by name emphasize that, making players think twice about the lives they’re carelessly taking away. The combat is uncomfortable as a result; burying an ax in someone’s chest is supposed to make you squirm.

That’s why it’s so bizarre that No Return brings over the exact same system, but removes the critical eye powering it. Battles that once felt tense and visceral become thoughtless amid meaningless wave defense rounds. Strip away all the narrative heft and we’re left with a stiff third-person shooter that doesn’t make for a pleasurable roguelike foundation.

That dissonance is inescapable throughout. It’s hard to remove No Return from The Last of Us Part II’s wider themes without turning one’s brain so off that we’d legally have to consider them dead. Part II is explicitly a meditation on cyclical violence, illustrating its horrible power and urging those locked in it to break the circle. So it’s head-scratching to launch a roguelike as a bonus coda to that story — a mode where players literally repeat cycles of violence.

There’s a world in which a sid mode like this very much works. The first Last of Us game famously included a multiplayer shooter mode called Factions that became a fan favorite (and it’s partly why some are so upset that The Last of Us Online has been canceled). Thematically, Factions isn’t at odds with Joel’s story. His tale has him waging war against the Fireflies, only for players to learn that the group isn’t evil. Factions emphasizes the idea that there are no pure good or bad guys in The Last of Us’ world by putting players on opposing teams both fighting for victory. It’s a perfect illustration of the story’s point; everybody playing sees themselves as the hero, just like Joel.

No Return could have served a similar function for Part II had it followed through with the base game’s themes. There’s a compelling version of it where players lose more of themselves with each run. Instead, it’s the opposite. Each new round unlocks more content, including goofy character skins. There are no consequences for loading up another run, only rewards.

Reaching Valhalla

Perhaps No Return sticks out as much as it does because it launched in such close proximity to a far more successful roguelike side mode. In December, Sony Santa Monica surprise released a free DLC for God of War Ragnarok titled Valhalla. Just like No Return, it has players slashing through rooms full of reused enemies and gaining temporary power-ups along the way. There’s one difference though, and it’s a major one: narrative purpose.

The story picks up after the events of Ragnarok, as Freya has asked Kratos to join her council as the new God of War. Kratos, worried about regressing back into the monster he once was, is reluctant to take on that mantle again. That insecurity is put to the test when he finds himself at Valhalla, a mysterious place where dead warriors face their past deeds. That creates a natural setup for a repeatable roguelike, as Kratos completes “runs” through Valhalla where he battles his demons. Literally.

Valhalla is an ambitious DLC that acts as a poignant epilogue for the entire God of War series. Trips through Valhalla change as the story progresses and Kratos fights old foes and even reenacts events from previous titles. Its best moment calls back to an iconic moment in the original God of War where Kratos would carelessly kill a soldier trapped in a cage to open a door. He once again has to carry out that shameful act, while actually reckoning with it this time. The mode’s power is in the way it makes players relive Kratos’ dark past over and over.

While that’s a dark premise, Valhalla tells a hopeful story by its conclusion. Through his trials, Kratos comes to terms with the person he used to be. He grows with each chapter of self-reflection and that’s reflected in the gameplay too. After each run, players can spend earned currency to gain permanent upgrades. Kratos grows stronger the more he confronts his old life and learns to move on. It’s a subtle decision, but an effective one that makes each upgrade feel more satisfying. Compare all of that to the more tacked on No Return.

It would be tempting to say that Valhalla works better because Ragnarok’s combat system is just more fun. That would be an oversimplification, though. Valhalla reinforces its roguelike premise at every turn with smart narrative decisions that give players the motivation to load up one more run. It’s a trick some of the genre’s best titles nail. Hades has Zagreus fighting to escape the suffocating clutches of his overbearing father. Returnal, another standout PlayStation 5 roguelike, has its hero fighting through the physical manifestation of a trauma she keeps reliving in her head. Deep combat is a welcome touch, but it’s those more narratively focused goals that really drive the action.

That’s not to say that every roguelike needs to be a high-concept idea that justifies its gameplay structure with story. Sometimes it’s enough for a game to be low-stakes fun, aiming for the same thrills that an entertaining Hollywood blockbuster provides. But Valhalla is one of those experiences that shows just how much more engaging video games can be when they use interactivity for a purpose. If I only could choose to play No Return or Valhalla, it wouldn’t be much of a choice at all. I’d much rather grow alongside Kratos than gun down hundreds of clickers and only get a lousy T-shirt to show for it.

The Last of Us Part 2 Remastered is available now on PS5.