- Every playthrough feels personal

- Amazing dialogue

- Relatable themes

- Educational and entertaining

- Illuminated manuscript-inspired visuals

- Frequent loading

- In need of an auto-advance option

All eyes will be on Pentiment this fall — but not necessarily for the right reasons. Although the modest game is just a small side passion project from Josh Sawyer (director of critically acclaimed games like Fallout: New Vegas and Pillars of Eternity), the delays of Redfall and Starfield mean that the game now has the high-pressure honor of being Microsoft’s only first-party game release of fall 2022. The creative ideas Sawyer was trying to express, and potentially the game’s legacy, will be defined by an unfortunate market position.

It’s fitting, then, that Pentiment is a narrative adventure game about the unexpected expectations and legacies placed upon art. The concept of the “death of the author” plays a major role throughout the game’s narrative, as art is ultimately given meaning by those who experience it. Although Pentiment might not be consumed in the most ideal way as it gets reduced to a piece of ammo in the never-ending console war, the game itself is a special work of fiction that’s worth engaging with outside of its circumstantial release.

Pentiment is a well-written adventure with an absolutely stunning art style and choice-based narrative that engages players in ways genre leaders like Telltale never quite did. Because of Sawyer’s vision and how this game was released, there will never be another game quite like it.

AP European History, visualized

As a high schooler enrolled in AP European History back in the day, I was fascinated by the Middle Ages. The Renaissance had yet to arrive, but religious reformation and more personal, creative art were emerging. It’s an exciting period of human history but an era that games rarely explore, as medieval fantasy is more widely appealing. Lucky for me, Pentiment nestles itself right in that period of history in both its story and art.

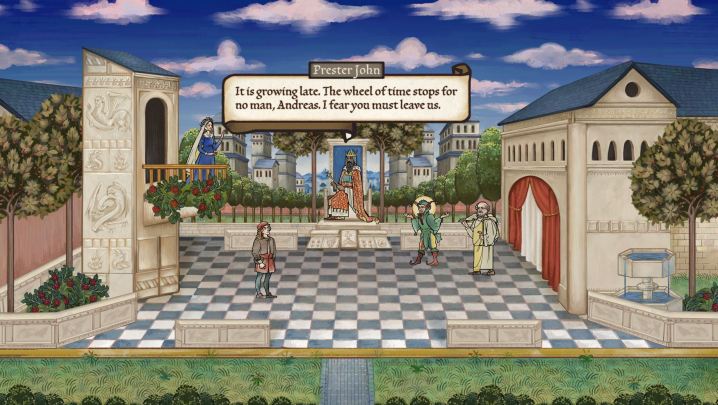

Pentiment takes place over several years in the 16th century, following journeyman Andreas Maler. He initially works on illuminated manuscripts for the Kiersan Abbey religious institution in the small Holy Roman Empire town of Tassing, but he soon finds himself forced to investigate the murders of individuals important to the town. During the game’s nine-hour, three-act run, Pentiment highlights how a town, its people, its religion, and its art change with time.

As someone who recently moved back to somewhere I used to live, I could personally relate to that idea. Unlike my situation, though, Andreas’ choices heavily influence what happens in Tassing over time. This is even demonstrated in subtler ways: I let a young girl steal Andreas’ hat in one of the game’s earlier acts, and in the final one, I saw her child wearing it as she reflected on her history as a thief. While Pentiment is a point-and-click adventure game that initially gives off tonal vibes similar to King’s Quest, it isn’t a puzzle-based game. Instead, it’s more of a narrative adventure game.

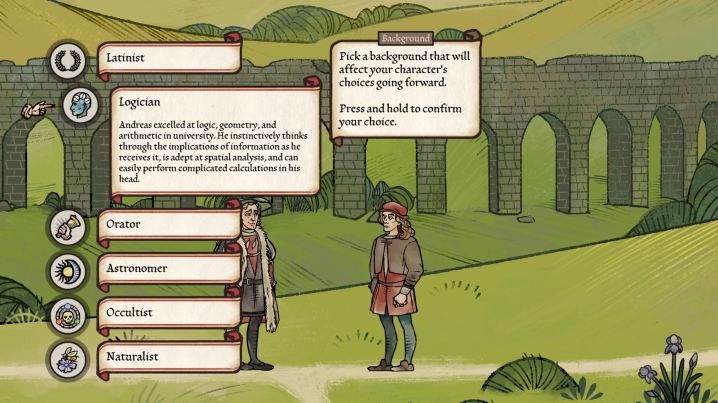

From the start, players choose information about Andreas’ background and personality that help inform his dialogue options (largely where and what he studied) while trying to solve the mystery of each murder, Andreas must travel around Tassing, speaking to townsfolk and performing tasks for them in order to learn more. This often comes in the way of conversation, where players must deftly choose their dialogue choices as they can impact a character’s decisions immediately afterward or years in the future — they might even result in a death sentence for a resident.

For example, my version of Andreas went to law school, so I could help a character I wanted to get information from prove that their land had no right to be seized by someone else. In turn, they gave me valuable information in solving one of the murders. The nonplayable characters in Tassing speak and behave like real people, and change over time based on what happens. This means Andreas’, and in turn, the player’s choices always have real, palpable consequences.

Pentiment does an excellent job of making my journey feel natural, with results that directly reflect my dialogue and action choices.

There’s no way to get through Pentiment without angering or offending somebody in Tassing — a young thief named Martin hated Andreas for the rest of the game after I called him out for being lazy during the opening act — but you might also learn some bits of information that many other players won’t. That’s partially because of the time management aspect, which channels a bit of Persona 5. Andreas can only do so much in a single day, so players must methodically decide how they want to spend the time as they can’t learn everything during a single playthrough. When choosing actions for the day, players are progressing Andreas’ investigation, gathering key evidence, and ultimately deciding who is punished for each crime. This setup perfectly pairs with the choice-driven narrative adventure setup, making the players’ journey feel even more personal since they must choose what to do.

Oftentimes in choice-driven games, it can feel like you’re missing out on huge swaths of content and not getting the whole experience without several replays. While I know there are details I missed in Pentiment, the game does an excellent job of making my journey feel natural, with results that directly reflect my dialogue and action choices. You can still replay it to see scenes you missed the first time, but it always feels like you’re getting a complete story from start to finish.

Death of the author

While it’s a murder mystery on the surface, Pentiment‘s fundamental themes are about the impact of art. It highlights how artists are compelled to create and establish their legacy through their work, but time ultimately dictates that legacy, proving the “death of the author” perspective true. Art inherits the meaning people give it. Pentiment also has a key twist that helps redefine the game, something I’ve only gotten out of Immortality and God of War: Ragnarok this year.

Pentiment is a clearly personal project for Sawyer, who is reflecting on his career as a game developer of some iconic and highly influential games. At the same time, it doesn’t feel like a self-aggrandizing puff piece, as it shows the shortcomings and ignorance of artists and is just as interested in preserving a culture not often portrayed in media. Tassing and its religious Kiersau Abbey institution may be fictional, but the game packs in timely references and features a glossary full of historical and religious figures, places, and terms so players can gain a greater appreciation for its setting. Pentiment makes you feel smart while playing it; this is the most I’ve learned about this time in European history since that AP Euro class.

Pretty presentation

Pentiment’s story becomes even more memorable because of its fantastic visuals. Its style is based on medieval art found in illustrations and woodcarvings that Andreas himself would work on. We aren’t at the realism of the Renaissance yet; body and facial proportions differ from character to character, while color and vibrancy are emphasized over realistic lighting and depth. The distinct style also helped me memorize the layout of Tassing by the end of the first act, and unique fonts for many of its citizens help make individual characters stand out.

Like its setting, this art style is wholly unique to Pentiment. By being purposefully imperfect, it’s gorgeous. Every frame of this game looks like it could be an actual drawing from that time, and some shot framings even reference real paintings. Those who appreciate art history and love games with a distinct visual look won’t find anything else that looks as unique as Pentiment.

While the visual presentation is outstanding, it does cause some pacing issues. Each part of the town in Tassing is its own painted image, so there’s lots of loading (in the form of literal page-turning) as Andreas walks from one part of town to another. It’s a novel trick at first but can be a slog later on as players have to venture from one side of the village to another with several quick loads in between.

Pentiment may be a smaller game on a much bigger stage than it was intended for, but it’s using the opportunity effectively.

You’ll also be reading a lot of dialogue in Pentiment, and it’s a bit cumbersome to get through. While an “Easy Read Fonts” accessibility option makes the game more palatable for those who can’t read or understand ligatures and historical lettering, players must manually click through each sentence. Not only that, but each textbox is animated, so players have to sit through letters being inked into a bubble even if they skip forward. I would greatly appreciate an auto-advance option for NPC dialogue in a future update, as it’d put off my impending carpal tunnel syndrome for a bit longer.

But there’s so much to love in Pentiment that those minor annoyances are worth muscling through. Pentiment is a wonderful game that tells a thematically poignant story that anyone who likes to create will empathize with. It avoids narrative adventure game trappings by making each experience feel wholly yours and encouraging multiple playthroughs.

Pentiment may be a smaller game on a much bigger stage than it was intended for, but it’s using the opportunity effectively. In fact, it’s all the more enjoyable for that. Although people will likely remember it more for its release positioning than the quality of the experience itself, it lives up to the challenge of being the only major Xbox first-party release this fall. More fittingly, it sets a high bar for the creative side projects that could come from various Xbox Game Studios developers in the future. Andreas would be proud.

Digital Trends reviewed Pentiment on PC via a Steam build provided by Microsoft.