You may not use Aereo, yet. The company, which has become almost outlaw infamous for its rebroadcasting of network television online, only exists in select metropolitan areas. But Aereo’s forthcoming Supreme Court case opposing the major powers of the TV broadcasting world may have major implications for the future of Internet TV, whether you use its services or not. On Wednesday, the company released a 100-page brief, making what is likely the final argument for its legality before its seminal battle in the high court next month.

Aereo, and its rival FilmOn, have been fighting a constant headwind of litigation from broadcasters like Fox, CBS, ABC, NBC, and others virtually since their inception. The companies rent out a tiny antenna to each user for a monthly fee, which allows the renter to watch network broadcasters from computers and mobile devices, and also to access cloud DVRs for recording content.

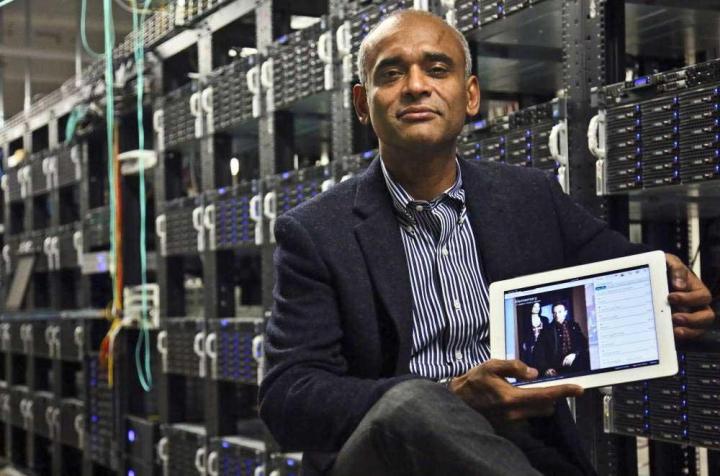

In his recent brief to the court, Aereo CEO Chet Kanoji once again outlined the argument that the company has broken no copyright laws. Kanoji’s brief maintains that under current law, “any consumer with an antenna is entitled to receive, watch, and make a personal recording of that content.” Aereo’s argument rests on the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision on Betamax, which upheld the right to record over-the-air content. In perhaps its most basic and grounded argument, the brief states “The evolution of technology from a black-and-white television connected to a rabbit-ear antenna and a Betamax to a high-definition television connected to a digital antenna and DVR has not changed those core principles.”

Kanoji specifically laid out the reasons he believes Aereo is legal under current law, and urged the Court not to rewrite the law, saying Aereo’s technology is simply the next step in evolution of an already legal practice. “The performance embodied in each transmission is the user’s playing of her personal recording – not the performance petitioners transmit to the public,” Kanoji writes. “The Copyright Act makes clear that the act of playing a recording is a performance distinct from any performance from which the recording is made.”

“Because the performance embodied in each transmission from Aereo’s equipment – the user’s playing of her recording – is available only to the individual user who created that recording, the performance is private, not public.”

Since Aereo maintains an individual antenna for every subscriber, stores their recordings individually, and rebroadcasts them only to that subscriber, it has always argued that each broadcast is a private performance, and therefore, protected as such under current copyright law. Networks on the other hand, have condemned Aereo and FilmOn’s services as illegal public performances, and have argued that the services threaten “irreparable damage” to their multi-billion dollar content revenue streams. In short, they want their cut, or they want Aereo shutdown.

When companies like ABC and CBS look at Aereo, they see a small stone rolling down a mountain that could start a landslide. At stake, they maintain, are lucrative licensing deals with companies such as Hulu, as well as content agreements with cable and satellite companies, all of which contribute to massive profits for the biggest networks in the business. And a threat to that paradigm, any threat, is one that the broadcasters are willing to fight all the way to the top floor of the American legal system.

Until recently, most arbiters in District Courts have ostensibly agreed with Aereo’s defense, denying injunctions against the service. However, as the battle has heated up, some recent turns have made the future of Aereo, FilmOn, and any other would-be competitors in the business of online broadcasting look very uncertain. Justice Kimball in Utah cut at the heart of Aereo’s defense, saying the company has taken advantage of a “perceived loophole” in copyright law, and that “Despite its attempts to design a device or process outside the scope of the 1976 Copyright Act, Aereo’s device or process transmits … copyrighted programs to the public.”

As the Washington Post reports, Kanoji is well aware that his service is an exploitation of loopholes in the current system, in the Rube Goldberg model. However, he urges the Court not to rewrite the law, simply because those loopholes exist. In fact, he insists that exploiting those loopholes is the whole point.

Public or private. Legal or illegal. Live or die. That’s what’s at stake next month, and Aereo knows it. In fact, in an interview with Bloomberg on Tuesday, Kanoji said that Aereo has “no plan B” if the court were to condemn its service, or order it to pay content licensing fees.

If the Supreme Court does decide against Aereo, it will have to tread lightly if it wants to maintain consumer freedoms and fair play in the marketplace. Make no mistake, what happens next month has a lot more gravity than the future of one simple online broadcasting service. It could forever alter the future of innovation, and outline who controls the path of Internet TV – and the ever-shifting streaming landscape ahead – for years to come.