Updated on 4-24-2015 by Malarie Gokey: Added official statement from Comcast CEO on the termination of Comcast’s plans to merge with Time Warner Cable.

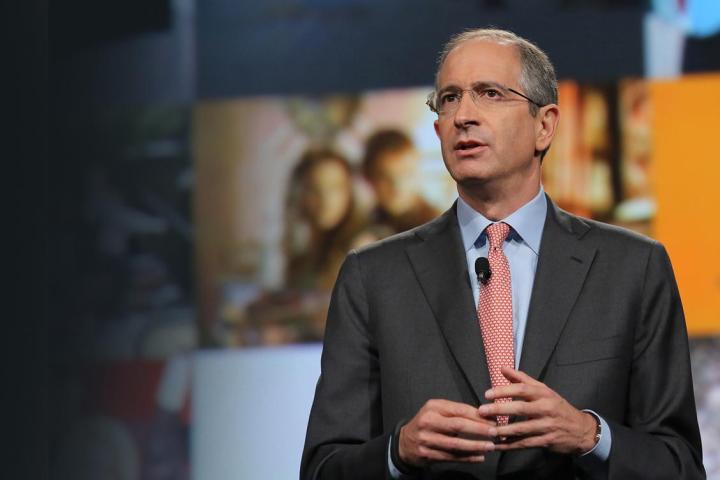

“Today, we move on. We structured this deal so that if the government didn’t agree, we could walk away.”

Comcast CEO Brian Roberts issued a statement in the morning, announcing the end of merger talks.

“Today, we move on,” he said in a statement. “Of course, we would have liked to bring our great products to new cities, but we structured this deal so that if the government didn’t agree, we could walk away.”

TWC CEO Robert Marcus also commented on the termination of the deal, saying that “Time Warner Cable is a one-of-a-kind asset” that continues “getting stronger,” thanks to its commitment to bringing “great experiences to our customers.”

On the other side of the issue, stand government officials, who claim that the end of Comcast’s attempts to merge with TWC is a great victory for consumers.

“The proposed transaction would have created a company with the most broadband and the video subscribers in the nation alongside the ownership of significant programming interests,” FCC chairman Tom Wheeler said in a press release.

Attorney General Eric Holder seconded Wheeler’s statement in his own comments on the failed merger.

“This is a victory not only for the Department of Justice, but also for providers of content and streaming services who work to bring innovative products to consumers across America and around the world,” Holder said in a statement.

It’s unknown exactly how many people were for or against the merger, but Comcast currently ranks as the eighth most hated company in the United States.

Opposition from gov’t forced Comcast to end merge talks

Once seen as all but inevitable, Comcast’s decision to abandon the merger is the result of widespread government opposition. In response to its plans, the Wall Street Journal reported that Federal Communications Commission (FCC) staff on Wednesday recommended issuing a “hearing designation order,” a move that would have put the $45.2 billion merger in front of an administrative law judge. Experts say it was a sign that the agency was wary of the buyout’s massive implications, and could have effectively put the kibosh on proceedings — The process, which the Journal describes as as “long” and “drawn out,” would have been the beginning of an uphill procedural battle for the cable giants.

“This is a victory for providers of content and streaming services who work to bring innovative products to consumers across America and around the world.”

Comcast executives met with FCC officials on Wednesday as part of the commission’s review, and were considering weighing in before the hearing moved forward, sources close to regulators said. To keep things on track, Comcast would’ve had to argue its case for the merger amid heightened scrutiny. History definitely wouldn’t have been on its side: in 2011, a similar hearing in conjunction with the filing of an antitrust lawsuit by the Justice Department spelled the end for AT&T and T-Mobile’s proposed $39 billion merger. And in 2002, the same procedure derailed a deal involving DirectTV and EchoStar, which provides the satellite fleet for DirecTV’s biggest competitor, Dish Network.

Even without the trouble from the FCC’s involvement, the Comcast/TWC merger was already under scrutiny from the Justice Department, which was “nearing a recommendation” to block the acquisition, according to Bloomberg.

Among a host of concerns, regulators were chiefly troubled by the amount of nationwide broadband and cable television Comcast would control after the merger — the company would have served 56.7 percent of U.S. broadband subscribers and 29 percent of the pay-TV market after scooping up Time Warner Cable. There were also major concerns about how Comcast might have used its influence to keep content off other platforms and the potential for it to limit competing video services in other ways, weighing Comcast’s adherence — or lack thereof — to the terms set during its 2011 acquisition of NBCUniversal. Comcast’s record for fair play in the open market simply isn’t stellar. In 2012, the FCC fined the company $800,000 for failing to offer “a reasonably priced broadband option to consumers who do not receive their cable service from the company.”

And then there’s the Hulu issue. Under the terms of the NBCUniversal deal, Comcast was supposed to refrain from influencing decisions for the streaming site, which is co-owned by Comcast, Disney-owned ABC, and 21st Century Fox. According to another WSJ report, Comcast may have influenced a decision to stop its megacorp partners from selling Hulu, promising to make the service “the nationwide streaming video platform for the cable TV industry.” Comcast has denied offering any influence on Hulu that would violate its previous agreements.

Next page: How ending this merger will affect other companies

Opposition from consumer advocacy groups also played a role

Outside of government opposition, the deal faced criticism from consumer advocacy groups and Internet-based businesses. In a letter addressed to FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, Dish Network, Internet backbone provider Cogent, Common Cause, Free Press, and several others argued that “the sheer size and scope of a combined Comcast/Time Warner Cable, coupled with its incentive to protect its core video business from innovative ‘over-the-top’ online video providers, would allow it to threaten nascent competition in so many different ways.”

The corporation has, until now, scrambled to pick up the pieces. Executives met with the Justice department this week “to air their views” and begin discussing possible concessions to help mitigate regulators’ concerns. A few weeks ago, Comcast sent its Executive VP David Cohen, along with Time Warner CFO Arthur Minson, to Washington D.C. to plead its case before a Senate Judiciary Committee. And in a separate initiative, Comcast recruited charitable organizations, politicians, and think-tanks to submit letters to federal regulators advocating the swift approval of the merger. However, it looks like the tide had already turned. There was simply too much opposition from all sides of the equation for the bemoaned communications goliath to continue its plans.

The end of this merger will affect other companies’ plans

Now that the end of the merger talks is official, it’s expected that Comcast’s decision will send shock waves throughout the industry. Charter Communication’s plan to buy Bright House Networks, which was contingent on the acquisition, will likely be put on hold, as will the creation of a new cable company from the 2.5 million subscribers in the Midwest and Southeast Comcast shed last year. But providers outside of the cable industry will likely be immune: A person familiar with the matter told the Journal that AT&T’s proposed purchase of DirectTV is “on much more solid ground” with the FCC’s staff.

Still, the disintegration of the Comcast/TWC deal is undoubtedly a huge win for consumers. The fusion of the already massive pair would’ve seen the creation of a behemoth with unmatched market share in several critical technology and communications segments. And if there’s anything John D. Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan, and Andrew Carnegie taught us, it’s that monopolies inevitably abuse their inherent power. Comcast’s position would’ve bestowed the company with unprecedented control over programming and broadband in the United States. As several entities both private and public have now made clear, entrusting infrastructure so monumentally crucial to a single entity, no matter how ostensibly honest its intentions, is a dangerous proposition.