Imagine someone spending $150,000 on a Porsche that had no speedometer. “This fine sports car can do zero to 60 in under three seconds.” Uh, how do I know? “Doesn’t it feel fast when you drive it? Trust us, it’s under three seconds.” Probably wouldn’t fly, would it?

And yet, this unlikely scenario is exactly what’s happening in the world of wireless audio.

Wireless audio — with its countless Bluetooth speakers, multi-room Wi-Fi speakers, and wireless earbuds — has become a multi-billion-dollar industry. And as buyers have flocked to these new devices, companies like Sony, Qualcomm, and Apple have been promising us better and better levels of audio quality, particularly over Bluetooth connections. Terms like “hi-res audio,” “lossless audio,” “CD-quality,” and “24-bit audio” are quickly becoming commonplace on product pages on Amazon. Amazingly, this isn’t just marketing techno-babble. With the right gear, you really can get much better wireless audio quality than we had 10 years ago.

There’s just one problem: it can be hard, if not impossible to verify that those new earbuds or wireless speakers are actually delivering what was promised. In short, wireless audio has a missing speedometer problem.

The compatibility problem

Most of us are painfully aware that products need to be compatible with each other to work. Want to charge your iPhone with the same cable your spouse uses on their Android device? Not gonna happen. (Not yet, anyway.)

The same thing is true of the wireless audio world, except that the incompatibilities are often hidden.

Most smartphone users don’t know or care about Bluetooth codecs, or which ones their phone supports. When they see a company like Sony touting the benefits of “wireless hi-res audio” on its flagship WH-1000XM5 headphones and WF-1000XM4 earbuds, the natural reaction is, “wow, that sounds really cool — I want it!” And sure enough, when you pair those headphones for the first time, you’re going to hear great sound. But only Android device owners will hear “wireless hi-res audio.”

That’s because Sony’s wireless hi-res claims rest on the use of its LDAC Bluetooth codec. Apple doesn’t support LDAC on any of its products, so wireless hi-res via LDAC won’t work if you own an iPhone. Sony buries this fact in a hard-to-find footnote on its product page for the WH-1000XM5: “Compatible devices supporting LDAC will be needed.”

I’m singling out Sony because it has been promoting the benefits of wireless hi-res audio longer than any other, but let’s be clear: this same deception via obfuscation is being done by lots of companies that sell wireless audio products on the strength of specific codec-enabled sound quality claims.

Should all of these companies slap a big “Not Compatible With Apple” sticker next to their audio quality promises? Maybe, but the compatibility problem isn’t limited to Apple’s universe of devices.

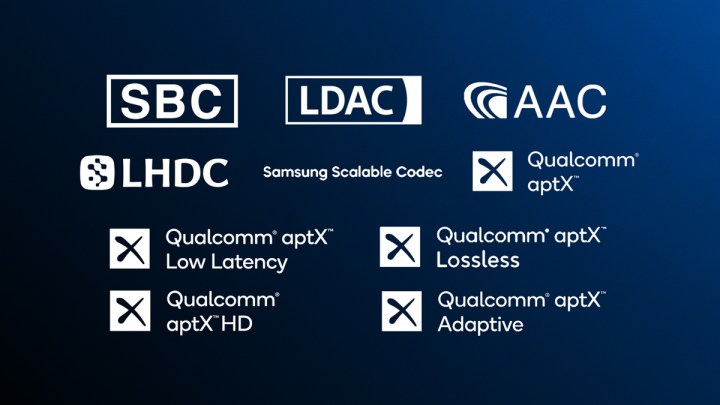

Like LDAC, Qualcomm’s aptX Adaptive codec and the LHDC codec provide similar high-quality wireless audio benefits, but unlike LDAC, they are not included in the base Android software. All Google Pixel phones, for example, lack aptX Adaptive and LHDC support.

What makes this compatibility problem so insidious is that it’s largely invisible. All Bluetooth audio devices must support the SBC codec, regardless of any other codecs they may also support. In other words, you’ll always hear something. Just not necessarily what you were promised.

The visibility problem

It would be nice to think that if your headphones and your phone both support the codec that is needed to deliver top-quality audio, then that’s really all you need to know. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. The quality of your wireless link plays a big role in how effectively a codec can do its job.

You can think of a high-quality codec like LDAC as a four-lane highway — there’s ample room for a lot of data to be passed back and forth. Just like a real highway, the actual speed at which vehicles can travel depends on things like the weather and the condition of the road itself.

Wireless links are also at the mercy of “weather” — in the form of wireless interference — which can play havoc with the transmission of audio. If you’ve ever had problems with your Wi-Fi when using a microwave oven, you’ve experienced what happens with wireless interference.

Unlike a real highway, there’s no way to know how fast your wireless link is performing. There’s simply no speedometer.

Why does it matter? Under normal, day-to-day circumstances, it doesn’t. If you’re at the gym, on a bus, or walking down the street, there’s almost nothing you can do to change the speed of your wireless link. However, when you’re at home or anywhere else you’ve chosen to sit back, relax, and enjoy those fancy new wireless headphones, you may have more control. Moving your phone closer to your headphones or finding a spot that’s away from lots of other electronics could help a lot, if only there were a way for you to see the effect that these changes produce.

The only way to know if you’re actually getting lossless CD-quality sound is if a mobile app tells you so.

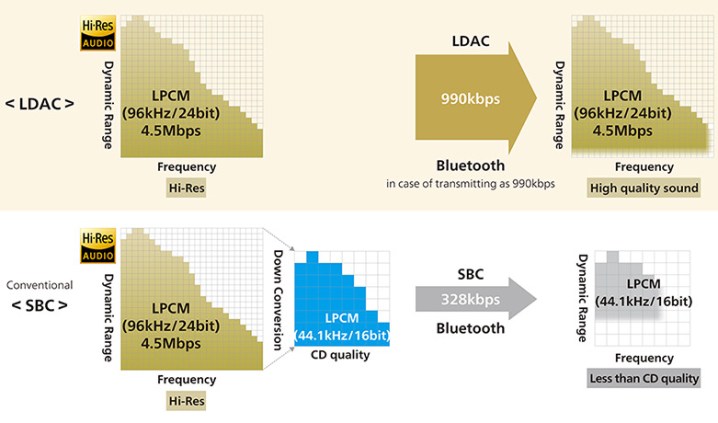

How much of a difference are we actually talking about? It depends on your gear. In order for LDAC to deliver its so-called wireless hi-res level of audio at 24-bit/96kHz, it needs to connect at 990 kilobits per second (Kbps) — which is almost the very limit of what a Bluetooth audio link can do. LDAC’s two other speeds, 330 and 660Kbps, can only offer a much-reduced version.

Qualcomm’s newest codec, aptX Lossless, is even more demanding. To deliver its claimed bit-perfect CD-quality audio, it needs a 1 megabit per second (Mbps) connection, otherwise, it falls back to a lower level of lossy compression.

The only way to know if you’re actually getting lossless CD-quality sound is if your headphones or earbuds ship with a mobile app that tells you so.

The visibility problem isn’t limited to the world of Bluetooth. Apple’s wireless HomePod smart speaker can be paired with an Apple TV 4K, which lets it act as a Dolby Atmos speaker for movies and TV shows — it compares very favorably with a soundbar especially when you use two HomePods as a stereo pair. Should you want to confirm that the sound you’re hearing is actually Dolby Atmos, there’s no way to check.

The Apple Home app, which acts as the defacto control center for your HomePods, can tell you whether the speaker is playing music from a streaming service like Apple Music, or whether it’s pumping out sound from the Apple TV (or even your own TV), but it won’t show you the format that’s playing.

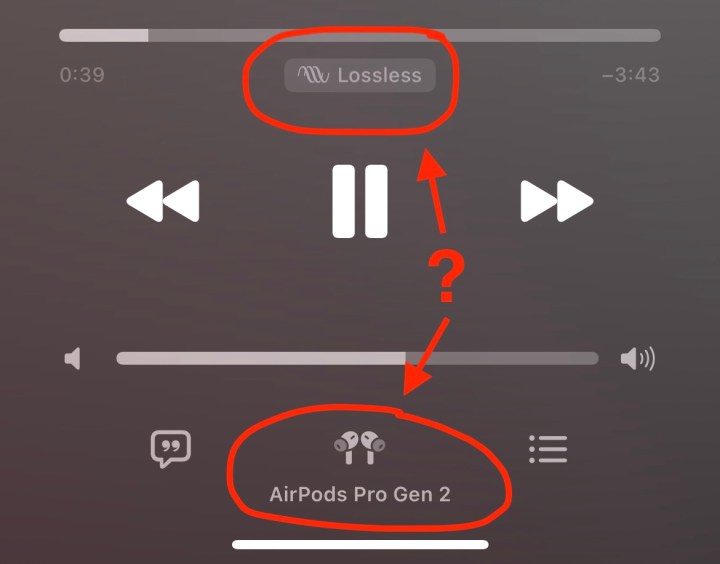

Apple’s guidance on this has been that if you see “Dolby Atmos” listed in the description of a movie or show on the Apple TV, then that’s what the HomePod will give you. That’s another “trust us” answer, and it doesn’t inspire much confidence. After all, Apple’s own Apple Music app will display a Lossless music icon even when you’re playing audio to a set of AirPods Pro, which do not support lossless audio. Apple would probably argue that in this case, the Lossless icon refers to the source track being played. But what good is a lossless track, if you can’t hear it as lossless audio?

Trust, but verify

The way to fix this gap between trust and verification is some kind of visual indicator, and it’s already standard practice in many areas of both the audio and video worlds. AV receivers have front panels that tell you exactly what kind of signal they’re processing. Soundbars will do the same thing — sometimes with a glowing LED on the speaker, and sometimes (like the Sonos Arc) it will tell you in the companion app. LG’s TVs will throw up a quick, three-second “bug” in the top right corner of the screen to let you know when you’re watching HDR content and a different bug for Dolby Vision content.

MQA, a company that has developed a proprietary hi-res audio format of the same name, has a strict rule for digital-to-analog converters (DACs) that can render MQA: they must illuminate an LED to indicate when MQA is the format being played. And not just any LED — it has to be magenta in color. It’s a pavlovian sense of comfort. If you see a magenta light, you know it’s MQA. Red, blue, or green? Not MQA.

Because wireless audio products inevitably involve the use of a smartphone or similar device, the best place for a visual indicator is the operating system itself. Ideally, it would show up in more than one place. There could be a mini indicator at the top of the screen, alongside the Wi-Fi and cell signal icons for quick reference. A second, more detailed readout could live inside your device’s Bluetooth menu, either on the main page or the page dedicated to the Bluetooth device in question.

The next best option would be to show the status inside an app. Nura, which made the first set of wireless earbuds to work with aptX Lossless, already does this inside the Nura app. Several apps, like the Sony Headphones app, will show you the codec being used (SBC, AAC, or LDAC) but not the bitrate, and that needs to change.

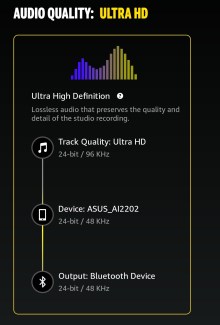

I think the gold standard for the moment, can be found not in an operating system or a headphone app, but in the Amazon Music app. When you select the quality indicator on the Now Playing screen, the app gives you a path-based explanation of your audio, from the quality of the track you’re playing, to the processing being applied by your device, to the signal being sent to your headphones, earbuds, or speaker.

Does any of this matter?

For the average person, as long as they hear something decent when they insert their earbuds, the whole question of audio quality is probably a minor consideration. Is this lossless audio? Is it hi-res? And if you’re at the gym and just need some pumped-up bass to help you get through your next set of reps, do you even care? (Not likely).

However, I think we can all agree on the notion that if you buy a product in part because of a performance claim, you should expect to enjoy all of the benefits of that performance, and that should include some kind of proof. You deserve to have a speedometer. To borrow from the famous astronomer and astrophysicist, Carl Sagan, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Or really, just any evidence at all.