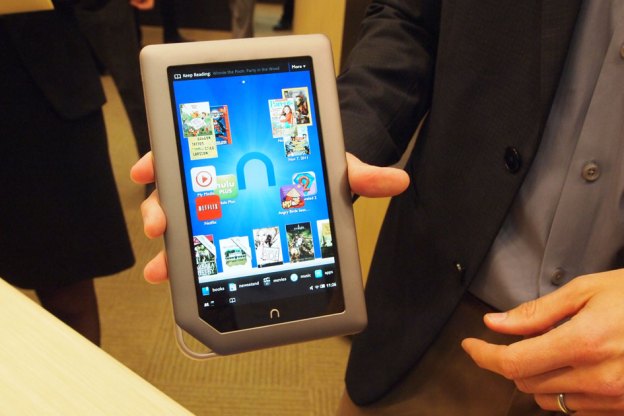

Barnes & Noble has announced its financial results for the second fiscal quarter of 2012 — which, by the vagaries of corporate finance, actually ended in late October 2011. Going into the holiday season, the company reported an overall decline in sales of 0.6 percent, while retail sales were down a full 1 percent year over year to $918 million for the quarter. However, there’s one very bright spot in Barnes & Noble’s numbers: the Nook. Sales of Nook devices, accessories, and (of course) digital content increased 85 percent during the quarter to $220 million, or nearly 12 percent of Barnes & Noble’s overall sales of $1.89 billion. Surprisingly, those figures were all tallied up before the in-time-for-the-holiday-season launch of the Nook Tablet, which the company is characterizing as “the fastest selling Nook product in the company’s history.”

Barnes & Noble has announced its financial results for the second fiscal quarter of 2012 — which, by the vagaries of corporate finance, actually ended in late October 2011. Going into the holiday season, the company reported an overall decline in sales of 0.6 percent, while retail sales were down a full 1 percent year over year to $918 million for the quarter. However, there’s one very bright spot in Barnes & Noble’s numbers: the Nook. Sales of Nook devices, accessories, and (of course) digital content increased 85 percent during the quarter to $220 million, or nearly 12 percent of Barnes & Noble’s overall sales of $1.89 billion. Surprisingly, those figures were all tallied up before the in-time-for-the-holiday-season launch of the Nook Tablet, which the company is characterizing as “the fastest selling Nook product in the company’s history.”

At the same time, Barnes & Noble appears to be amping up its legal defense against Microsoft, adding noted attorney David Boies to its team. (The high-profile addition was first noted by FOSS Patents.) Boies was in the news most recently for representing players in the recent NBA lockout, but he has some notoriety in tech circles, too. He’s best known for leading one of the firms heading up Oracle’s patent battle against Google over Java in Android, and for leading the U.S. Justice Department’s monopoly case against Microsoft back in the 1990s. The software company SCO also used Boies in its quixotic, long-term battle against Linux, which eventually ended in SCO’s categorical defeat.

Barnes & Noble might be having success with its Nook, but why is it sinking considerable financial resources into a patent battle with Microsoft that appears to have absolutely no financial upside for the company? Is Barnes & Noble merely acting out of principle, or is there something else going on here?

Microsoft’s case against Barnes & Noble

Microsoft’s case against Barnes & Noble

Microsoft’s case with Barnes & Noble goes back to March of this year, when the company filed suit claiming that the company’s Android-based Nook ereader products violate several Microsoft patents. The case has similarities against suits Microsoft has brought against other Android device makers, like Motorola (which is in the process of being acquired by Google), although the actual patents involved are mostly different. (Google is asserting Motorola’s Android devices violate 20 Microsoft patents, whereas it only claims Barnes & Noble is violating five — just one of those is also cited in the Motorola case.)

However, the basics of Microsoft’s case against Barnes & Noble appear to be similar to its issues with Motorola and other Android device makers: Microsoft sees proprietary technology in Android itself, including ways of moving through content, accessing the Web, and interacting with documents and e-books. From Microsoft’s point of view, those innovations represent millions of dollars in investment and R&D. They’re patented, and anyone who uses Android needs to pay Microsoft for use of those technologies.

Microsoft has had remarkable luck getting Android device makers to hand over royalties: the company recently claimed over half of all Android devices are now covered by patent agreements with Microsoft. (In the U.S. smartphone market, Microsoft claims 53 percent of Android devices pay royalties.) Microsoft has licensing agreements with HTC, Samsung, Acer, ViewSonic, Onkyo, Itronix, Velocity Micro, Wistron, Quanta, and Compol, while it is suing Inventec, Foxconn, Motorola Mobility, and Barnes & Noble for infringement based on their use of Android.

Microsoft’s suit against Barnes & Noble also targets Inventec and Foxconn, which manufacture Nook products. The company characterized the suit as only the seventh time in Microsoft’s history it has proactively sued somebody over patent infringement. Microsoft feels litigation is its last resort: It would rather reach licensing deals and (effortlessly) collect money than have to take companies to court.

Barnes & Noble’s defense

For its part, Barnes & Noble has characterized Microsoft’s lawsuit over Android-based Nook tablets as a ploy to reduce competition in the mobile device marketplace. How? Barnes & Noble argues Microsoft’s intent behind demanding royalties from Android device makers is to raise their costs: That puts up barriers to Android device makers even getting into the marketplace, and will make it easier for Microsoft and its preferred partners to compete in the tablet marketplace (you know, when they eventually get around to it in 2012, more than two years after the iPad’s initial launch). According to Barnes & Noble, Microsoft’s strategy is to abuse the patent system and pressure device makers with “arbitrary, outmoded, [and] non-essential” patents (PDF).

Barnes & Noble’s argument against Microsoft dodges the issue of whether Microsoft’s patent claims are actually valid, and doesn’t make any attempt to assert that Barnes & Noble devices don’t infringe on those patents. Where Motorola is defending itself from Microsoft’s suit by denying the validity of Microsoft’s patents and filing a countersuit alleging that Microsoft is the true infringer, Barnes & Noble doesn’t have a portfolio of patents and other intellectual property to back it up in the mobile technology arena. So Barnes & Noble can’t fight a patent battle the way a technology company might. Instead, Barnes & Noble is attempting to shift the case into antitrust territory, arguing Microsoft is abusing its position in the market to suppress competition and innovation. Where Barnes & Noble doesn’t have a huge patent library at its disposal to defend itself against Microsoft, it has no trouble asserting its Nook product line is innovative and competitive.

How does the money work out?

So here’s the thing: Barnes & Noble is characterizing its stand against Google on principle: It doesn’t want to cave in to a massive corporation trying to tramp all over the little guy and preserve the tablet and mobile device market for itself.

However, it’s difficult to identify a financial upside to Barnes & Noble pursuing an expensive court case against Microsoft, particularly if the case were to actually get to trial. Putting well-known Microsoft foe David Boies on your legal team isn’t cheap, and Barnes & Noble already has top-flight law firms working the Microsoft case, including Kenyon & Kenyon (which specializes in intellectual property cases) and Cravath, Swaine, & Moore (which has long-time ties to IBM).

Although Barnes & Noble is heading into what ought to be a profitable holiday season (boosted in part by the Nook Tablet), the company continues to face financial difficulties. Sure, B&N had sales of $1.89 billion in its most recent quarter, but that translated into a net loss of $6.6 million for the quarter. That’s better than than $12.6 million it lost in the same quarter a year ago, but it doesn’t give the kinds of returns investors seek, or put Barnes & Noble on a good footing to develop technology and an ecosystem that can compete with the likes of Amazon.com.

Doing the math

Doing the math

The terms of Microsoft’s licensing deals with other Android device makers haven’t been disclosed, so no one really knows how much money Microsoft is earning from devices it sells. However, some industry watchers (like Citi’s Walter Pritchard) have placed Microsoft’s per-device royalty on Android phones from HTC at $5 per device. Like Amazon, Barnes & Noble has never disclosed how many e-readers it has sold, although it expects to sell “millions” of devices during the current holiday quarter.

For some back-of-the-envelope comparisons, let’s say Microsoft’s licensing deal with companies like HTC and Samsung covers the same essential patent set at issue in Microsoft’s case against Motorola. In proportional terms, that potentially puts Barnes & Noble on the hook for about one quarter the licensing burden of Android phone makers—five infringement counts against Barnes & Noble compared to twenty against Motorola. (Yes, this is very fuzzy: not all patents are equal, nor are all patent license negotiations.) But let’s say Barnes & Noble could realistically negotiate a per-device royalty rate on the patents at issue in the Microsoft suit for $1 to $3 per device.

Barnes & Noble expects to sell “millions” of Nook devices this quarter, and we know its Nook business was 85 percent larger during its most recent quarter than a year ago. Let’s say (perhaps generously) Barnes & Noble can sell between 2 and 5 million Nook devices this quarter; that would mean the company sold between 1.2 and 2.9 million Nooks a year ago, and pro-rating that out across the last year with a bit of a bump for the 2010 holiday season could very roughly put total Nook device sales between 8 and (say) 20 million units. At the low end of units and licensing fees, that would mean Barnes & Noble could have been on the hook to Microsoft for $8 million in licensing fees in the last year; on the high end, it could be almost $60 million.

Possibilities

If Barnes & Noble really is looking at having to pay Microsoft $60 million in royalties to cover its use of Android in Nook devices from the third calendar quarter of 2010 through today, then Barnes & Noble’s stand on anticompetitive principles makes sense: that figure could conceivably represent as much as 10 percent off the top of Barnes & Noble’s entire Nook business for that time period. However, if the figure is closer to the low-end $8 million, I estimate it would amount to just over one percent of Barnes & Noble’s Nook business.

These — admittedly very vague — figures point to three possibilities:

- Microsoft’s patent licensing terms are so draconian that Barnes & Noble believes the fees will gut their Nook business; therefore, an expensive court battle is worth the cost up front.

- Barnes & Noble believes its Nook business will become so large and/or long-lived that paying for an expensive court battle now will be cheaper in the long run than paying patent licensing throughout the lifetime of the Nook ecosystem.

- Barnes & Noble is getting some help with its legal bills.

I tend to discount the first notion. If Microsoft is charging a $5-per-device royalty on HTC Android phones that have retail values of $400 to $450 (unsubsidized), that’s a royalty rate of 1 to 1.5 percent per device. That tends to eliminate the high end of Barnes & Noble’s potential licensing costs: The Nook Color runs $200, the Nook Tablet runs $250, even if they incurred the same licensing proportions as Android smartphones (despite fewer patents being invoked). Although the company is under no obligation, Microsoft is demonstrating willingness to sign Android licensing agreements with anybody — after all, it’s free money, so long as device makers believe Microsoft’s patent claims against Android could be enforceable.

On the second point, there seems little doubt Barnes & Noble is betting on the Nook platform’s long-term future. It could well believe that having its devices encumbered by patent royalties is a significant downside. However, there’s no law that says the Nook platform has to be on Android forever: if Android becomes too messy, Barnes & Noble could look to transition the platform to something like Tizen (if that ever gets off the ground). Such a transition might be easier for the Nook, because the devices aren’t as invested in the Android app ecosystem as, say, an Android smartphone.

That leaves the third idea. Microsoft has two major legal actions against Android device makers: The first — and probably most significant — is against Motorola, while the second is against Barnes & Noble (and its manufacturing partners Foxconn and Inventec). To protect Motorola against Microsoft patent suits, Google is in the process of acquiring the company, meaning Microsoft isn’t just taking on Motorola, it’s taking on Google and the sum of its intellectual property portfolio and deep pockets.

Barnes & Noble, while the subject of buyout overtures from the likes of Liberty Media, has seen no such public support from Google.

It’s pretty easy to argue that Google has more to lose in the Barnes & Noble case than Barnes & Noble. If Microsoft were to win a court victory that Android devices infringed on Microsoft patents, it would have a significant impact across the entire Android ecosystem: Android would go from being “free” in quotes (challenged by Microsoft, Oracle, and others, but nothing settled yet) to “not free” — encumbered by patents owned by one of the largest technology companies on the planet.

And that might explain how Barnes & Noble can justify putting a high-profile attorney like David Boies on its legal team.