Many of you will have heard stories about Foxconn. It’s the Chinese manufacturing company that makes iPhones, iPads, and a ton of other gadgets. But unless you’re an industry insider, there’s really only one reason you’ll know the name, and that’s because of all the stories about strikes, under-age workers, riots, and worse, threats of suicide by the workers in the factories.

However, not every smartphone company has Foxconn building its phones, and one in particular has chosen to do things very differently. That company is Vertu, makers of obscenely expensive luxury smartphones, and we were invited to see its factory in action. However, there was no traveling to China involved, as Vertu builds all its phones in a factory just outside the village of Church Crookham, in the south east of England.

Each phone is made by hand, primarily by one person.

It was obvious Vertu’s factory wouldn’t be anything like the image we have of places like Foxconn, but what would it be like? Would it be techno-cool, where space-age phones are assembled in ice-white rooms by an army of cyborg technicians, or would it have floors made of gold and rooms separated by silk curtains, like Liberace’s place if he had been into tech? As it turns out, it was neither.

Spread over one level, Vertu’s open plan layout made it feel spacious, and although modern, it was not unlike any other head office. When one usually thinks of a factory, whether its building phones, cars or something else, one imagines it to be a visual and audible overload, with machines providing a rhythmical accompaniment to workers’ similarly metronomic actions. Upon entering the Vertu factory, after donning anti-static shoe straps and an unflattering blue lab coat, it became clear this wasn’t always the case. While the sound of machinery was there, it wasn’t the sound of assembly, but of components such as keyboards being stress tested. The volume was muted, so it soon vanished into the background.

Our guide was Jonathan Haynes, Vertu’s head of production quality and a veteran of nearly three decades in the mobile industry. He has been with Vertu from the start, and knows not only each and every product, but could at one time, tell which engineer was responsible for building a Vertu phone just by looking at it. This is an important distinction between how Vertu builds phones and how others do, as each one is made by hand, primarily by one person. No parts can be seen whizzing along conveyor belts or passing through the hands of dozens of workers at a dizzying speed; instead, Vertu’s hardware is built at a desk and the entire production team numbers just 45.

Each phone is made up of at least 200 different components, and each has to be fitted in order. To do this, engineers work from a blueprint displayed on a monitor, and assemble each one using a pre-built starter kit and parts from a motorized carousel which sits next to them.

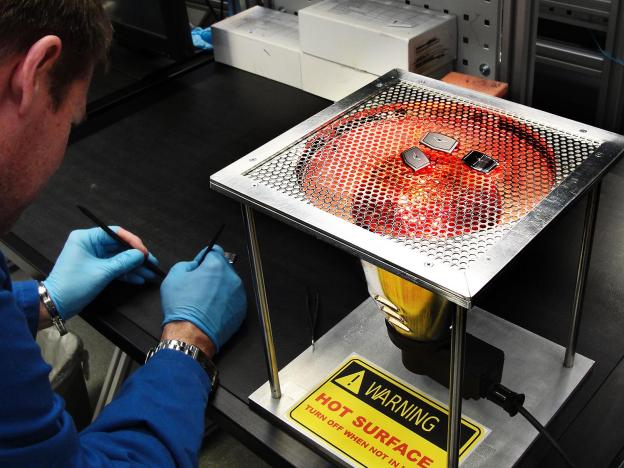

A tray is moved into position, the part selected, and the phone gradually takes shape. The construction of a Vertu phone has more in common with a watch than a phone produced in Foxconn’s factories – in fact, the minuscule screws used are often sourced from the industry. It’s precision work, and requires the use of purpose-built tools, including a powered screwdriver which sucks up the screw and turns it at the required rate, as the work is so delicate.

Vertu’s attention to detail is obvious, but it soon becomes clear that being conscientious isn’t enough.

Vertu’s attention to detail is obvious, but it soon becomes clear that being conscientious isn’t enough. Take the battery cover used on the Signature phone. This is a part which is rarely removed, but if you did so, you’d find an intricate pattern etched into the underside. Haynes freely admitted it would be easy to laser etch it into the metal, but that’s not the Vertu way, and instead a machine is used to engine turn the pattern, a process where rubber bits infused with shards of metal polish the pattern into the surface. This results in 15 percent of the parts being discarded for not being quite up to Vertu’s insanely high standards. Why go to all this trouble? Because a connoisseur will know just by running their fingertip over it whether it has been engine turned or lazily lasered in.

As the phones near completion, the screens are introduced. Vertu is one of the pioneers of using sapphire to cover its displays, a material which can only be cut with diamond tipped tools. While the screens are prepared offsite, Vertu bonds the sapphire glass to the display at its factory following 48 hours of polishing, a process unique in the industry. They’re bonded in a class 7 clean room, where the staff are clothed in hooded protective gear and the air is extracted through a system built into the windows. If you’re wondering just how clean the room is, class 7 is one step down from being suitable for surgery.

With the phone almost complete, it’s placed into a testing bay, which looked something like the the Ecto-Containment Unit from Ghostbusters. In here, it’s subjected to more than 300 individual tests, from making calls and testing audio frequencies, to each button being pressed. The tests continue after the machine has given the phone the ok, primarily because Vertu works with many natural products – leather, for example – where defects are a fact of life. So extensive is the battery of tests, the time they take matches the time it takes to make the phone in the first place.

Compared to the rest of the industry, Vertu’s tests are more extensive, and quality control is so important, the time dedicated to them is only expected to increase. In each section, you’ll find a display cabinet with various phones mounted inside, and underneath are draws filled with components. The phones represent the pinnacle of build quality at Vertu, and are there for engineers to match the final products against to ensure nothing has changed. It all ends with the sales packages being put together, which like the phones themselves, have more in common with the boxes that usually contain a Rolex or Patek Philippe watch, than they do with the cardboard packaging used for regular phones.

It felt good to reacquaint myself with the Vertu TI, and it’s still the understated Titanium Pure Black model that I’d love to slip in my pocket and hope no-one notices. If it were a car, it would be a matte black Lamborghini Aventador, and it commands the same type of attention. My smartphone of choice for the day was the Samsung Galaxy S3, and during a conversation with Hutch Hutchison, the Head of Design, we shared an app using NFC. So solid is the titanium and ceramic bodyshell on the TI, it felt like it would crumple the plastic rear panel of the S3 as they touched. It was like comparing the sound of a door closing on a $30,000 Hyundai Santa Fe, with one on a $85,000 Range Rover. The sapphire, titanium, leather and ceramics used in its construction mean there’s no need to wait for Motorola’s rumored super tough phone, as the TI is incredibly strong (go on, try and scratch titanium or sapphire), ensuring it always looks as good as it did on day one.

Chatting with Vertu’s Head of Product, Ignacio Germade, after the tour was complete, the conversation turned to the cost of the Vertu TI and the impact the working environment has on it. Vertu’s staff retention is high and the workforce skilled and well paid, facts which must be factored into the cost of the phone. It’s not the only reason a TI is considerably more expensive than a Samsung or Apple phone, but it’s a key part of the sum.

If it were a car, the Vertu TI would be a matte black Lamborghini Aventador.

As we discovered, that also means we won’t be hearing any horror stories about the conditions at Vertu’s factory, and although many find it impossible to justify spending more money for “less”, we wonder how many feel the same way knowing it also guaranteed a safe, pleasant and fair work environment in which the phone is built. While we’re not sure other companies should be looking to copy Vertu’s approach to the spec race, or adopt its pricing (seriously, please don’t), and of course, there is a considerable difference between the amount of phones produced by Apple and the amount produced by Vertu, but we’re sure there’s something to be learned from the way it puts its phones together.