“The first program executed under Section 215 of the Patriot Act authorizes the collection of telephone metadata only,” said National Security Agency Director General Keith Alexander before the House Intelligence Committed on June 18. Called for a rare public hearing on the NSA’s activities, Alexander uttered this statement just a week after the first of an ongoing set of top-secret leaks from former contractor Edward J. Snowden.

“As you’ve heard before, the metadata is only the telephone numbers, and contact, the time and date of the call, and the duration of that call,” Alexander continued. “This authority does not, therefore, allow the government to listen in on anyone’s telephone calls, even that of a terrorist.”

Predictive analytics is about revealing “unvolunteered truths” about people.

Let’s put aside for a moment the question of whether this dragnet data collection should happen, and ask a crucial question now that we know that it is: How is it possible that our phone metadata can be both innocuous and key to preventing, say, a group or individual from releasing poisonous gas in the New York City subway system?

A detailed answer to that question is classified. But based on what we know about the techniques available, an educated look at the possibilities points us in one direction: Predictive analytics.

Predictive analytics 101

Put entirely too simply, predictive analytics is a way of using “Big Data” techniques to predict possible outcomes, from results of presidential elections to the behavior of individual people. Depending on the application, predictive analytic data often includes demographic information, family and marital status, purchasing history, past weather patterns, business transaction histories, social media activity, website clicks, and, of course, telephone metadata, all of which help shape the map of an possible underlying reality.

“It’s about creating the ability to not only predict the future, but to influence it,” says Dr. Eric Siegel, author and founder of the Predictive Analytics World conferences. Further, he explains, it’s about revealing “unvolunteered truths” about people.

We know the NSA uses a variety of Big Data techniques and technologies, some of which the agency itself developed. The question then is: How are they using computer-assisted prediction?

How we use predictive analytics

The public may have first become aware of predictive analytics in 2012, thanks to an article in The New York Times Magazine by Charles Duhigg. You may remember its bombshell anecdote: A father, having discovered coupons from Target offering discounts on baby gear sent to his young daughter, became outraged at the big box retailer for apparently trying to coerce the teenager into having sex. In fact, Target’s in-house data analysts had devised an algorithm that deduced whether particular customers were pregnant based on seemingly random changes in their purchasing habits.

The man later apologized to a Target manager; his daughter, he had since discovered, was due a few months later.

This is, to date, the most visceral story we have about the powers of predictive analytics to derive facts about the world through data points and algorithms. But the fruits of predictive analytics are all around us, in less creepy forms: Netflix’s video recommendations, email spam filters, and Google Now, the technology giant’s virtual “personal assistant” for mobile devices, are all prime examples of predictive analytics at work. Rather than accurately predicting your due date, Google Now simply suggests a less congested route to your office.

In his aptly titled new book, Predictive Analytics: The Power to Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie or Die, Siegel lays out multiple poignant examples of how predictive analytics is predicting more than just which customers to send ads.

Hewlett-Packard, for instance, has developed a “Flight Risk” score for its employees that “foretells whether you’re likely to leave your job,” writes Siegel. Credit card companies accurately decipher which of us will make late payments. Parole boards figure out which inmates are most likely to commit another crime upon release. Cell phone companies figure out who and when to serve offers for discounted phones. The U.S. military uncovers which soldiers can handle the highly demanding life in the Special Forces. Life insurance providers predict when people will die. The list goes on – and is getting bigger by the day.

Future crime

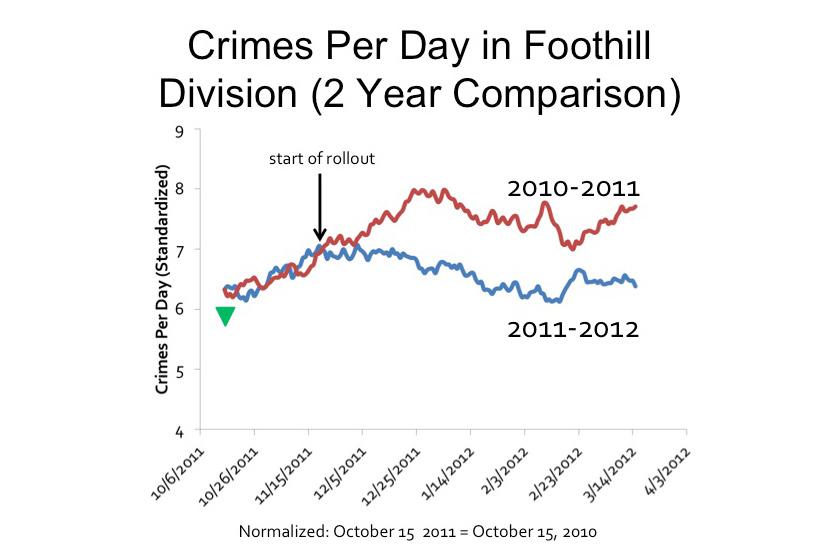

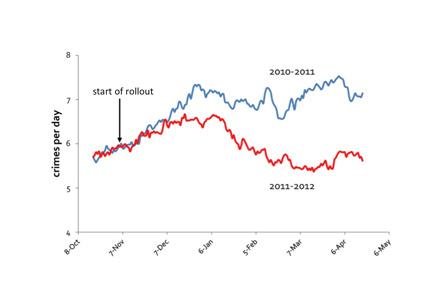

In recent years, predictive analytics has entered a new realm: Policing. The highest-profile example of so-called “predictive policing” began in Santa Cruz, California, in 2011. Santa Clara University professor George Mohler generated predictions of crime “hot spots” based on historical crime data dating back to 2006, as well as new data added to the system every day. The result of that experiment is a propriety software called PredPol, created in 2012 by Mohler and P. Jeffrey Brantingham of UCLA, which has since been adopted by an increasing number of police departments around the country, including the Los Angeles Police Department.

While the term “predictive policing” inevitably conjures scenes from Minority Report, the reality has far more in common with the Waze traffic app than a dystopian future envisioned by three sun-deprived creatures in a vat of KY Jelly. In other words, PredPol does not let officers predict who will commit a crime, but where a crime will likely happen, regardless of who commits it.

PredPol is designed to be “completely blind to people,” says Zach Friend, a Santa Cruz district supervisor and police consultant, who spearheaded the development of PredPol. “The only four inputs into the system are date, time, crime type, and location.”

Police have long used “hot spot” mapping tools, which rely upon historical crime data to help departments pinpoint problem areas. PredPol is the next evolution in hot spot policing. Think of it as a traditional hot spot map that’s updating in real time and deploying officers to specific locations at specific times where and when a specific crime is deemed likely.

Crime data can often be sent to patrol cars as it comes in from victims, giving officers a birds eye view of the surrounding criminal landscape, as it evolves minute by minute.

Powerful though predictive policing may be, the limitation imposed on the types of data used in crime prediction is a key component to preventing PredPol from edging into dangerous territory, says Friend.

“I wouldn’t want to say that ‘Andrew’ is going to be [committing a specific crime],” says Friend. “That’s the Minority Report stuff. What we wanted instead is, ‘This location, this [latitude and longitude], 500-foot by 500-foot, has the highest probability of a burglary occurring during this shift. That’s all we wanted to do.”

The result of this tactic is a clear and continuous drop in crime. Santa Cruz saw burglaries drop by 19 percent in 2012, compared to the same period in 2011. And Los Angeles saw a 12 percent crime reduction soon after adopting PredPol. For all of 2012, overall crime in L.A. dropped by 1.4 percent, and violent crime dropped 8.2 percent.

While PredPol may be committed to limiting its system to time and location predictions, other data scientists have begun to take the technology a step further. According to Bloomberg News, Jim Adler, a former chief privacy officer for data broker Intelius, has created a computer model that can “accurately” predict whether an individual will commit a felony. Adler’s software initially made such predictions using a small number of telling data points, including gender, eye and skin color, traffic citations, criminal history, and “whether the individual has tattoos,” according to Bloomberg.

Predictions and the NSA

The rise of PredPol and other predictive policing efforts opens a window into what kinds of predictive tools the NSA may have at its disposal, and possibly how the spy agency uses those tools. For example, during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the NSA utilized predictive models and other Big Data tools created by Silicon Valley company Palantir, to help connect the dots between known terrorists. According to government officials, Palantir’s technology even helped the military foil suicide bomber and roadside bomber attacks. Similar tools from Palantir are now used by the NSA, FBI, and CIA, which provided monetary backing to the company.

Some of the most powerful Big Data weapons were developed by the NSA itself. Chief among these is a system called Accumulo (pdf), which enables the NSA to map trillions of “nodes” (data points) and “edges” (connections between two or more data points), to create a discernable picture of the world’s communications using telephone metadata and internet traffic data collected under its now-controversial PRISM program.

According to a former international law enforcement agent, who requested anonymity due to ongoing professional obligations, the NSA can likely pinpoint suspicious communications activity using a predictive model, based on call records and Internet activity. The predictions may include deriving name, age, and gender data, or plotting likely future locations of individual people.

“Predictive analysis can often provide an idea of a subject’s age and gender based solely on call frequency and duration,” says the former agent. “Call duration and call frequency can be indicators of the significance of the callers to each other.”

In the same vein, geographic location data can be used “to make inferences about how criminal organizations operate,” says the agent. The same goes for terrorist groups, and the information can be used to deduce who is, and is not, working together on a potential plot, and where these actors might meet.

“Predictive analysis might indicate when it’s likely someone will show up at a particular locations,” says the agent. “Similarly, if a model gives a high probability that two individuals will meet in a time window and that window elapses, it can be an indication something has changed in their relationship. That might just be a flat tire, or it might be a falling-out.”

This information may be more valuable than direct surveillance – it’s spying 2.0

“All these metadata things are the nuts and bolts – the sort of syntactic things known [about a person] that are often extremely revealing, not to mention a lot easier to deal with than the content, such as the typed message of an email or spoken words during a phone call,” says Siegel.

Siegel points out that, in any particular case, what a target says online or over the phone may prove to be “the most important of all [for an investigation], but are also not necessarily going to trump the metadata. And the metadata itself is going to make a huge difference.”

Metadata is so revealing because it is “easy to aggregate and analyze” in its raw form, according to Princeton Computer Science Prof. Edward Felten, in a recent court filing (pdf) written on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union, which is suing (pdf) top Obama administration officials over the NSA’s collection of telephone metadata. Speech and the meaning of emails are, by contrast, much more difficult for computers to decipher, explains Felter. Add to that the significant increase in computing power and the plummeting cost of storage, and it’s possible for the NSA to easily garner “sensitive details about our everyday lives.”

“Sophisticated computing tools permit the analysis of large datasets to identify embedded patterns and relationships, including personal details, habits, and behaviors,” writes Felten. “As a result, individual pieces of data that previously carried less potential to expose private information may now, in the aggregate, reveal sensitive details about our everyday lives – details that we had no intent or expectation of sharing.”

Compare this to the contents of a telephone call, which requires far more legwork to shape into a usable form. To analyze phone calls, “the government would first have to transcribe the calls and then determine which parts of the conversation are interesting and relevant,” explains Felten. “Assuming that a call is transcribed correctly, the government must still try to determine the meaning of the conversation: When a surveillance target is recorded saying ‘the package will be delivered next week,’ are they talking about an order they placed from an online retailer, a shipment of drugs being sent through the mail, or a terrorist attack? Parsing and interpreting such information, even when performed manually, is exceptionally difficult.”

To illustrate the powers of predictive analytics further, Felten lays out the following hypothetical:

“A young woman calls her gynecologist; then immediately calls her mother; then a man who, during the past few months, she had repeatedly spoken to on the telephone after 11pm; followed by a call to a family planning center that also offers abortions. A likely storyline emerges that would not be as evident by examining the record of a single telephone call.”

Expand the telephone metadata collect over a period of months or years, and “many of these kinds of patterns will emerge once the collected phone records are subjected to even the most basic analytic techniques,” writes Felten. One can easily imagine how these techniques could be used to root out terrorists – or abused to spy on innocent people.

While we do not know the extent to which the NSA employs predictive modeling, officials have confirmed that it uses analytics for purposes similar to those outlined by Felter. As David Hurry, chief researcher for the NSA’s computer scientist division, told InformationWeek in 2012, “By bringing data sets together, it’s allowed us to see things in the data that we didn’t necessarily see from looking at the data from one point or another.”

Limitations of prediction

As powerful a tool as predictive analytics may be, its proprietors are quick to point out that it is not a silver bullet or a magic crystal ball.

“Generally, it’s not about accurate predictions,” says Siegel. “It’s about predicting significantly better than guessing. And that’s true for most applications, including law enforcement applications.”

Due to the limitations of predictive analytics, experts believe the NSA likely uses this Big Data technique as a jumping off point, or to enhance other parts of ongoing investigations.

“In my experience predictive modeling alone is not used to try to identify suspects or persons of interest,” says our unnamed source. “I can’t say that it has never been used that way. I have, however, used predictive modeling techniques in the course of medium- and long-term investigations opened for other reasons.”

Dean Abbott, founder of Abbott Analytics, says that the telephone metadata collected by the NSA may be “particularly useful in connecting high-risk individuals with others whom the NSA may not know beforehand are connected to the person of interest.” He adds, however, that predictive tools are likely only helpful when combined with a variety of other intelligence.

“These networks are usually best used as lead-generation engines,” writes Abbott on the Predictive Analytics World blog. Used this way, Abbott explains, predictive analytics and link analysis, such as the connections revealed through Accumulo, are “tremendously powerful” tools.

Drawing the line

Limited though predictive analytics may be, experts believe the potential for the technique to transform the nature of privacy and civil liberties is potent.

It is “fairly easy to predict” whether a criminal will repeat his pattern of crime, says John Elder, CEO of Elder Research Inc., the largest dedicated data analytics company in the U.S.. “Now, do you do like that Tom Cruise movie where you intercept somebody before they do the crime? That’s probably going too far in terms of allowing humans to take responsibility for their own actions.”

Big Data systems can also be tailored with privacy concerns built in. Accumulo, for example, has complex tagging system, known as Column Visibility, which the NSA built in to limit, at every level, which analysts can see what types of data through the use of security labels. It is likely that this aspect of Accumulo is what the NSA means when it refers to built-in civil liberty and privacy protections.

“Individual pieces of data … may now, in the aggregate, reveal sensitive details about our everyday lives.”

“… Predictive policing forecasts will end up being seen as a ‘plus factor’ to find reasonable suspicion,” writes Ferguson. “However, the use of predictive policing forecasts alone will not constitute sufficient information to justify reasonable suspicion or probable cause for a Fourth Amendment seizure.”

In other words, by Ferguson’s assessment, predictive modeling may be used to unearth our innermost secrets – but the courts likely won’t let police search us on that intelligence alone.

For now, the debate over the NSA’s surveillance remains firmly focused on the collection of the data, not the ways in which it is likely used to derive more intelligence. In July, the U.S. House of Representatives narrowly defeated a bill that would have largely cut off the NSA’s ability to collect telephone metadata not directly connected to an ongoing investigation. And now, following recent revelations that the NSA violated privacy protection rules thousands of times in 2012, legislators are ramping up efforts to push back against the NSA with at least three new bills.

While we may see limitations on data collection by the NSA, the use of predictive analytics to help weed out criminals and terrorists – or even just to sell us diapers and cell phones – isn’t going anywhere, says Siegel.

“The power of predictive analytics should not be underestimated in the same way that the power of a knife should not be,” he says. “A knife could be used for good or for evil. I think outlawing knives entirely is not on the table.”