Ahead of the 90th Academy Awards on Sunday, our Oscar Effects series puts the spotlight on each of the five movies nominated for “Visual Effects,” looking at the amazing tricks filmmakers and their effects teams used to make each of these films stand out as visual spectacles.

Earlier this year, director Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 seemingly did the impossible by crafting a well-received sequel to one of the most beloved sci-fi films of all time, Ridley Scott’s 1982 cyberpunk drama Blade Runner.

A big part of the sequel’s success came from its tonal and visual similarities to the original film, as well as its willingness to further explore that world. Set 31 years after the events of Blade Runner, which cast Harrison Ford as a former police officer tasked with hunting down bioengineered humanoid “replicants,” Blade Runner 2049 dives back into that dystopian Los Angeles landscape with Ryan Gosling cast in the role of a policeman charged with “retiring” rogue replicants.

With so much praise heaped upon the amazing visual elements of Blade Runner 2049, Digital Trends spoke with the film’s Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor, John Nelson (Gladiator, Iron Man), to learn how some of the film’s most memorable scenes were created.

Digital Trends: Coming into this project, did you have a sense of the nostalgic baggage a Blade Runner sequel carries? Did that change anything about the way you approached it?

John Nelson: Well, it was always a labor of love. It wasn’t wasted on anyone that we were doing a sequel to the favorite movie of lots of people.

So, no pressure or anything…

Exactly. Don’t screw it up! [Laughs]

Everybody dearly loved the project. We loved the director and we certainly loved the original movie, so everybody was really, really working hard. I’m known in the business as someone who works a lot, and on this one I probably put in more hours than I’ve ever done before. I think it was just because everyone wanted it to be all it could be. And I think we did it.

Naturally, there are a couple of shots I’d still work on, but I’m pretty happy with it.

The future we see in the original Blade Runner was sort of extrapolated from where Ridley Scott and his team saw the world going. That’s very different from where we are now in a lot of ways. How did you approach extrapolating a future based on the original film’s vision?

“We love this, but we don’t want to make the same movie.”

Early on, everyone looked at the original film and said, “We love this, but we don’t want to make the same movie.” Fortunately for us, we had a brilliant director in Denis Villeneuve. But Denis and Ridley Scott are like brilliant painters, and they paint in different ways. So [Blade Runner 2049] was very definitely Denis’ vision from the beginning, even though everyone had so much respect for the first movie.

There were parts of [the new movie] that were going to be inherited legacies from the original movie, but for the most part, it was just small things, like the Pan Am building or the Atari logo. We knew there would be differences.

What sort of differences were a product of Villeneuve’s vision for the film?

In our movie, there’s not quite so much industry. I’m from Detroit, so I know a lot about dystopian industry, and I asked Denis if he wanted that in the movie. He said, “No, I want it to be more like what I remembered growing up in Montreal. I want it to be really cold and snowing.” He said to me, “John, it should be like Montreal in February.”

It’s interesting you say that, because I went to school near Quebec, and that’s exactly what some of the ground-level scenes felt like: Montreal in winter.

That’s great to hear. That’s exactly what Denis wanted.

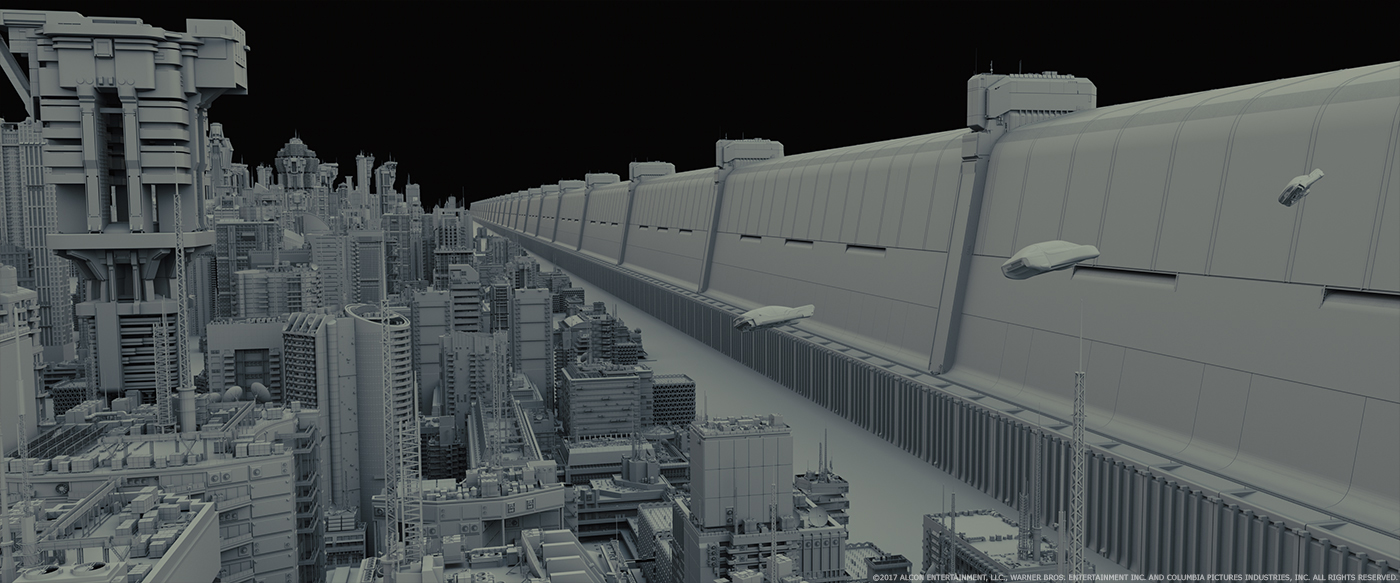

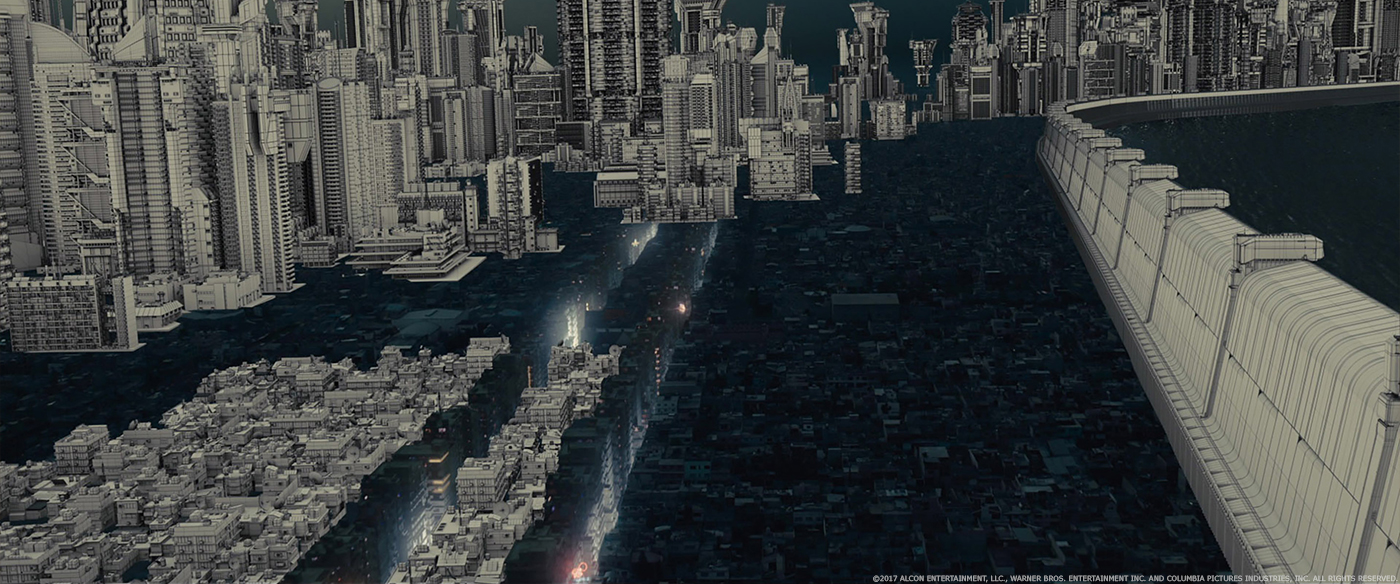

So once we got that environment down, we went through and designed the cities. … We designed this brutalistic architecture which sort of takes on a little bit of what is in the first movie, without the industry. We took away all the cars and took away all the trees, and then we designed different scales of that brutalistic architecture: Normal scale, large scale, and super scale.

Whenever we could, we’d shoot plates. We saw some stuff from Mexico City that Denis and Roger [Deakins, Director of Photography] liked, so I scouted and found out when the cloudiest days in Mexico City were. I tried to arrange our helicopter schedule according to it. I Google-scouted earlier, so I had all the paths I wanted for the flights over Mexico City. We were lucky we got cloudy weather, and we were able to shoot our paths.

After all of that, the last thing we did was to drop the street, creating these sunken canyons. So not only did we make the top of the city higher, we made the bottom of the city lower. That was just Los Angeles.

One scene that’s particularly amazing is the threesome sequence with Ana de Armas, Mackenzie Davis, and Ryan Gosling, with de Armas’ holographic character Joi superimposed over Davis’ human character, Mariette, as they interact with Ryan’s character. How was that scene created?

I knew introducing Joi as a hologram and bringing her out into the rain was going to be hard, but the hardest thing with Joi was that scene — what I refer to as “the merge.”

Early on, we tried to define Joi as a hologram. Most of the holograms we saw in movies we didn’t like. We tested a bunch of stuff and didn’t like it, but finally we started thinking about volume. If you have a glass or a bottle near you, put it in front of you — because that’s the visual example we used. We came up with this idea of the “back-facing shell.”

It doesn’t look like a computer graphic, it looks like a real performance

On a glass or a bottle, if you hold it up and look at it, you can see the front of it. But if it’s transparent enough, you can also see through to the back. If you rotate it, you’ll realize that the front might rotate left-to-right but the back will rotate right-to-left.

So after lots of testing, we shot the two actresses separately and had multiple cameras all around the room that could record their movement from many different angles. We then positioned geometry in the computer that was exactly the same as the actresses, frame by frame. That way, we could map the front of the actresses on that geometry surface — that glass or bottle, if you want to call it that. And then for the back, we’d create the backwards version of what the cameras captured — because if you look through a glass, the back label appears backwards. So we had to create that.

That’s what you get with Joi. She looks real, because she’s made from the performance of the actress, Ana, and that performance is projected onto geometry. So it doesn’t look like a computer graphic, it looks like a real performance … she has actual volume, because the volume is made from the back shell.

So how did you bring those performances together and get them to sync up?

So we would shoot each of the women with Ryan separately. They would each do their performance, then Denis would pick a take that he liked, and then I would need about five minutes with the script supervisor Jessica [Clothier] and we would go through and literally break it down while everyone was waiting. We would break it down to every movement, along the lines of, “At three seconds she raises her hand, then at four seconds she touches his face, then at five seconds she steps closer to him,” and so on.

Then I would take an iPad and put it in front of Ryan’s face and line up Ana, for example, so that Joi’s eyes were right where Mariette’s eyes were in the scene. I had this big idea that when their eyes would align, that would be this magic moment.

So I would line her up, and then I’d pull the iPad out, so she wouldn’t be looking at the iPad, and we’d feed her those directions. “Now you raise your hand. Now you touch his face. Now you step closer,” and so on. …What I really went nuts over, was once I started seeing their eyes line up, it really started getting very interesting to me. As humans, we cue on eyes so much. It’s no secret that it’s my favorite scene in the movie.

It’s always great to hear filmmakers get genuinely excited about a particular scene that challenged them and paid off in the end.

Well, that’s the magic. You’re using all of this visual effects technology to make something feel very organic. In most cases, visual effects are used as this super stimulus — basically, “let’s throw a billion things at the viewer.” But in this movie, we tried to restrain that. Instead of throwing a billion things at the viewer, why don’t we throw a hundred things, but have them be really, really good?

Less is more?

Instead of throwing a billion things at the viewer, why don’t we throw a hundred things, but have them be really, really good?

Yes. And I think that was a good thing for us. It definitely comes from Denis and that whole concept of “less is more.” Particularly with the merge scene, you get these moments of magic. We could see that right away when we were doing our stuff on set.

Even double-exposing one woman over the other, you could see this take form. We would get one woman’s performance, then the other woman’s performance, and then they would merge and there would be this third woman that didn’t look quite like either of them — she was a mixture of the two women — and that woman would throw a look and give her performance.

There’s a lot of buzz lately about the use of digitally created characters based on the likeness of actors who have aged beyond the timeframe the movie calls for, or are deceased. Every project seems to tackle it in a different way. How did you approach the task of bringing back Sean Young’s character, Rachael, looking the way she did in the 1982 movie?

I knew early on we needed to do a shoot with a double for the body and then replace from the neck up, including the hair. What we did, though, was to really get deep into it.

We were in contact with Sean and scanned her the way she is now, as well as the body double, an actress named Loren Peta. … we scanned Sean and Loren, and I did some testing. There were two things we needed to do: We needed to make a CG model that looks real, which is one hard thing to do, but we also had to make it act like Sean in the original movie.

To make the model exactly right, we found a life cast [a mold of someone’s face] of Sean that someone had done a few years later when she was 28 or 29. It was close, but it wasn’t perfect. When you’re 19 or 20, you’re in this perfect zone in life. It’s just right. So this cast wasn’t the way we needed to go. We then extrapolated from the scans we did of Sean now to create her face skeleton, and we could see how it’s different today than it was when she was 28. Then we went back to the old Blade Runner and used that [depiction of Sean] in our extrapolation, too. Because the underneath skeleton and muscles were right, we could extrapolate backwards to make what we needed.

Again, this seems like a fairly involved process for a relatively brief scene.

It was, and we didn’t stop there.

When we showed that to the director and producer, they said it looks like Sean — but really, it looks like a girl who looks like Sean Young … I thought about that a lot and how people remember Sean. She’s done a lot of great films, like No Way Out and others, but I think it’s safe to say most people know her from Blade Runner. So I thought, let’s get Blade Runner and drill into what makes her the way she is in it.

Her performance and look in Blade Runner was about her bone structure and where she was in her life at this seemingly perfect time. And we looked at what makes Rachael who she is, too. Part of it was her makeup. I learned so much about makeup. [Laughs] I pulled women aside from the crew and learned what’s special about 1980s makeup, and we did tests to learn how people move their eyes with that makeup and whatnot.

At what point did you sit back and realize you finally have it, that you’ve recreated Rachael?

The big breakthrough came when we went in and encoded some of Rachael’s mannerisms … There’s this moment in the first movie when she walks out and Deckard asks her if the owl in the building is artificial, and she says, “Yes.” He says, “Is it expensive?” And she says, “Very. I’m Rachael.” She has this super-confident attitude. She knows she’s special, beautiful, powerful … she’s toying with him a bit.

So we looked at those performance and said, “Okay, let’s go back in and take what we can to finish the modeling from the little cues we got there.” So we took scenes from the original movie and I had [visual effects studio] MPC — the team was led there by Richard Clegg — take four scenes from the original Blade Runner and replace the digital double by really drilling into her mannerisms in those scenes … then I showed it to Denis and the producers. They said, “This is cool, John, but why are we looking at this? This is the original movie.” I said, “You’re looking at it because one of those shots is a digital double.”

They couldn’t tell the difference?

We had her shift from confidence to longing as she reaches out and touches his face

No. So now we knew we had a model that looked like Sean, and it was time to make her act. … When they meet, Denis said, “It’s like two people who are in love and haven’t seen each other in 20 years and see each other at a train station, and they can’t help themselves. The emotion just rushes out.” So we had her shift from confidence to longing, as she reaches out and touches his face and makes contact with him, and then says her lines. When he rejects her, she goes from confidence, to longing, to rejection.

So we went back in the original movie to find moments in the original movie when she hit these same emotions. We reverse-engineered it using those points, and then at the same time, we did some facial motion-capture with Sean and with Loren. It was good reference to see how Sean’s face works, but we really used those moments from the original movie to imbue that emotion.

How much of what we saw on the screen was real, and how much was digitally created?

Her hair is all digital hair, but we made some of the digital hair not perfectly groomed on the side so there were some flyaway hairs, just like it would be on any person — a little bit of hair that’s not perfect. So when Roger’s backlight hits it, it’s not perfect. It feels real.

But really it came down to drilling into the nuances. Ask anyone: It’s very hard. We’re all so accustomed to looking at faces, since the time we’re just months old, and we expect to see tons of information in faces. We really didn’t stop until we hit that same threshold, and those shots took a very, very long time.

Talking to visual effects producers, I’m always fascinated by how much work goes into creating a scene that looks like it’s completely natural. The better you are at what you do and the harder you work, the more invisible your efforts are.

It’s funny, because as I was leaving a screening of the film, these guys in front of me were talking to each other about it. One says to the other, “Wow. Sean Young has really been working out!” [Laughs]

I typically ask visual effects supervisors about their favorite scenes from the film, but I think you’ve answered that question many times over already.

It’s true. But the cities are great, too, and on this movie everyone really did such a great job. And the matte paintings — like when you see the orphanage for the first time — were so beautiful. I really like using matte paintings, because they don’t look like CG and they give the film a different feel. But I’m happy with all the work that was done. We had eight vendors. We had 1200 visual effects. And the work feels consistent throughout all of it.

Blade Runner 2049 was released in theaters October 6, 2017. The 90th Academy Awards ceremony will air Sunday, March 4, at 8pm ET on ABC.

Updated February 26, 2018, for Oscar Effects series.