The Hunger Games franchise is back in cinemas with the release of The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes. Set 60 years before Katniss Everdeen stepped into the arena, the prequel follows a young Coriolanus Snow as he becomes the character fans loved to hate in the original saga. Although solid, if overstuffed and flawed, The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes is nowhere near the level of the original tetralogy starring Oscar-winner Jennifer Lawrence as the rebellious archer. Because, while it’s set in the same world and features most of the same themes, Ballad misses all the nuance and impactful storytelling that made The Hunger Games such a phenomenon.

As Catching Fire turns 10, and with The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes in theaters, it’s the perfect time to look back at the 2013 film’s legacy. Time has been nothing but kind to Catching Fire, cementing it not only as the undisputed victor of the YA battle but as a near-perfect film for its time and place.

The YA craze

To understand Catching Fire‘s overwhelming success and legacy, one must first understand the context in which it premiered. The YA genre was strong but not a juggernaut; Harry Potter was more fantasy than YA, same as Percy Jackson, Narnia, and all the other copycats chasing after The Boy Who Lived’s crown. The main representative of the YA genre, and the franchise that truly took it to the mainstream, was Twilight.

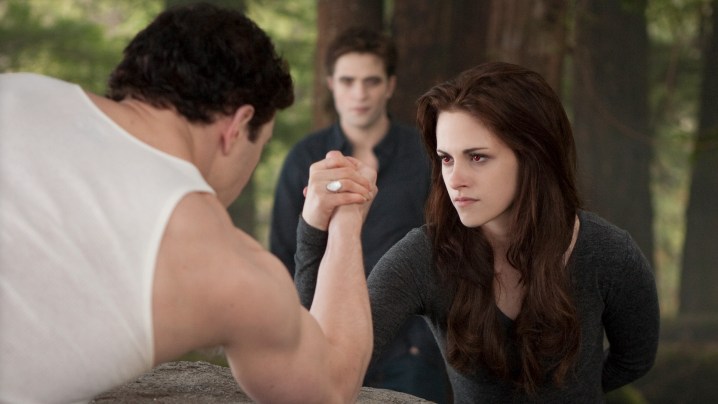

Sufficient time has passed for us to admit the Twilight movies are not just bad; they’re god awful. They’re ineptly made, terribly paced, and outright stupid. Robert Pattinson and Academy Award nominee Kristen Stewart are good at playing the roles they’re saddled with, but everything else about the movies, including their co-stars, is terrible. The Twilight movies are atrocious, and not even nostalgia can make you believe otherwise; if anything, rewatching them now just makes you realize how ridiculous and borderline embarrassing they are. Don’t get me wrong, they’re still a fun time, but hardly anyone watches them and feels anything other than cringe.

Enter The Hunger Games, a film that wore its political and social undertones on its sleeve and featured a once-in-a-generation talent as the protagonist. The Hunger Games came out months after The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 1, quite possibly the worst entry in the vampire saga. Because it was pure and unadulterated YA, The Hunger Games was seen as the logical heir to the soon-to-be-defunct Twilight, and to call it an upgrade would be generous. The Hunger Games is a good movie by itself, but next to Twilight, it’s borderline masterful.

Audiences responded enthusiastically. There was an eagerness from critics and viewers to acknowledge The Hunger Games, the first truly great YA movie. Katniss Everdeen single-handedly legitimized the genre, proving that teen-centric storylines could offer the same “elevated” entertainment that became so popular in the 2010s, and things were just getting started. One year later, Catching Fire capitalized on its predecessor’s goodwill, instantly becoming the pinnacle of the YA genre. If The Hunger Games towered over its peers, Catching Fire outright dwarfed them.

The YA genre is not difficult to analyze. From its love for the dystopian setting to its penchant for casting truly impressive young talent, YA movies are all cut from the same cloth – The Hunger Games cloth, and specifically, Catching Fire. The second entry in Katniss’ saga defied all expectations and boundaries, producing a thought-provoking, exhilarating, tremendously compelling narrative capable of standing among the best films of 2014, and I mean that unironically. Look at the 2014 nominees for Best Picture, and tell me Catching Fire is not better than at least half of them. The fact that a teen-centric, dystopian action movie could provoke such a reaction from critics and audiences was and remains nothing short of impressive, especially today, when blockbusters are struggling to even be taken seriously as cinematic endeavors, let alone works of genuine art.

The cast on fire

A lot has been said about Catching Fire‘s strengths: its tight, fast-paced plot, increased stakes, and the stellar additions of some of the best characters in The Hunger Games. However, I think Catching Fire‘s greatest strength relies on its cast. The saga had already proven its ability to pull some of the most inspired casting choices in modern blockbusters, from Elizabeth Banks to the scene-stealing Stanley Tucci to, of course, Jennifer Lawrence herself.

However, Catching Fire took things to a new level of cool with its new cast. You have the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman and Jeffrey Wright hamming it up, plus a perfectly cast Sam Claflin as the devilish Finnick. But then you get to the ever-underrated Jena Malone; then you turn around and see Lynn Cohen. And who is that playing Wiress? Emmy-winner Amanda Plummer?! While other franchises were casting big names left and right, Catching Fire was giving familiar yet underrated actors a chance to shine, and we were all the better for it.

More importantly, Catching Fire‘s greatest triumph is cementing Katniss as a genuine, three-dimensional, and inspiring character rather than just a YA figurehead. The Hunger Games might’ve introduced the girl, but Catching Fire quite literally lit her up. To do so, the film does two crucial things. First, it expands on the saga’s two most complex and fascinating relationships; contrary to what you might think, I’m not talking about Katniss and Peeta, much less Katniss and Gale. Rather, I mean Katniss and Haymitch and, of course, Katniss and Snow.

Katniss Everdeen is the star of the Hunger Games franchise, and Lawrence valiantly steers the ship. However, both Woody Harrelson’s Haymitch and Donald Sutherland’s President Snow are crucial parts of the saga. Catching Fire explores both relationships, resulting in refreshing and thoughtful takes on the traditional mentor-mentee and hero-villain dynamics. The first film introduces Haymitch as a mentor, but Catching Fire expands his role to that of a friend and peer to Katniss; he might be more experienced, but he’s not more mature. There’s a unique rhythm to their interactions; perhaps they don’t like each other entirely, but they are comfortable around one another, providing something they have both needed for years: tranquility. It’s a tremendously impactful and surprisingly tender relationship that would become the heart of the series.

On the other hand, Katniss and Snow are locked in a curious dance. Far too focused on each other to stop yet too tired to keep going, both characters face each other with respect if not necessarily admiration. Because Katniss — and Lawrence herself — is older than her years and Snow/Sutherland never treats her as anything less than a worthy opponent, their rivalry doesn’t feel like that of a teenager fighting against a remarkably stupid adult.

The second thing the film does to cement Katniss’ legacy is acknowledging that Jennifer Lawrence is its biggest asset. Her performance is the key to the franchise’s success, and she delivers her best work in Catching Fire. Wisely, she never tries to make Katniss a “chosen one,” much less a leader or even a rebel; she only ever tries to make her alive. There’s a reluctance in her performance, stoicism mixed with barely-conceited aversion and a heavy dose of anger. And yet Lawrence is so convincing, so overwhelming, so electrifying that we believe that a teenager can become the face of a revolution. The spell, however, was too strong because it wasn’t just Katniss who became the Mockingjay; it was Jennifer Lawrence herself.

Like The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes is about to learn, Catching Fire made it so that the saga would only work when rising on Lawrence’s capable shoulders. The story and worldbuilding are compelling, but will we care about Panem if Lawrence isn’t in it? The answer is probably a resounding “no.”

The life of a victor

Catching Fire avoids the trappings many YA projects face by giving its characters dignity and gravitas. Building on Lawrence’s reputation as a tough-as-nails actress with a maturity beyond her years, Catching Fire defied and redefined the constrictions of YA. The question so often asked in other similar movies is, how can these barely-prepared teenagers take on supposedly mighty enemies with nothing but a few makeshift weapons and some barely-concealed chutzpah?

The answer is they don’t. Katniss didn’t spark a rebellion by being exemplary; she did it by embracing her humanity and proving that there’s power in being ordinary. Catching Fire proves that The Hunger Games is not a one-against-the-world story but rather a tale about how one person can influence entire establishments.

In hindsight, what Catching Fire achieved was tremendous, so much so that it convinced Hollywood that the YA genre was a gold mine waiting to be exploited. Except it wasn’t — not even its sequels could match its success, let alone any other wannabe copycat. Catching Fire came out at the right time, with the right cast and the right narrative. It was a trailblazer that set an impossibly high bar no one else matched. In many ways, Catching Fire set up its saga for failure by peaking too early and pretty much buried the YA genre before it even began living.

But so what? Catching Fire was never indebted to the YA genre or even its franchise, only to itself, and thank god for that. It did what needed to be done with its head held high, something not many blockbusters can say. And now, 10 years later, it is finally enjoying it: the life of a victor.

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire is streaming on Peacock.