The Disney original film Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers seemingly managed to pull off a trifecta with a reboot of the Rescue Rangers franchise that won over fans of the original series, young audiences, and critics when it premiered on Disney+ in May.

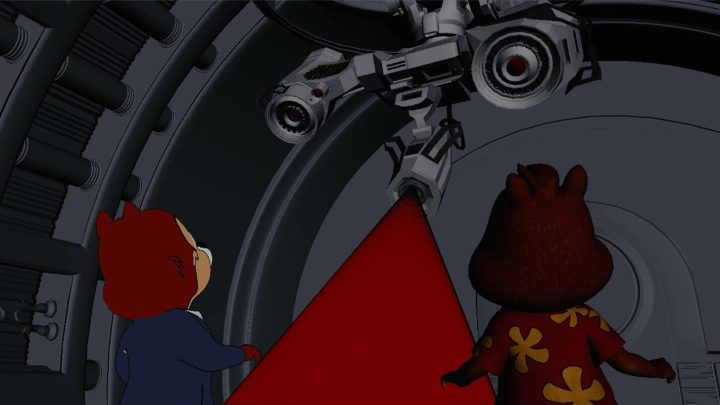

Directed by Akiva Schaffer (Hot Rod), Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers is set in a world where animated characters and humans coexist, and finds the titular duo reunited when one of their former costars in the Rescue Rangers series goes missing. With Chip depicted in the more traditional, hand-drawn style of 2D animation in the series and Dale getting a 3D, computer-generated visual makeover, the pair find themselves interacting with characters from various eras of animation over the years — as well as humans — while attempting to solve the mystery.

Bringing all of those characters together and blending myriad animation styles was no small feat for the Rescue Rangers team, and Digital Trends spoke to visual effects studio MPC‘s Oscar-winning production supervisor on the film, Steven Preeg, to find out how they made it possible.

Digital Trends: I read that MPC worked on more than 1450 VFX shots for the film. That’s a lot! Is that correct?

Steven Preeg: Yeah! I mean, there are bigger projects, like an Avengers movie, but this is a Disney+ project where they come in and say, “Oh, it’s streaming, so there’s not quite the same budget as a feature,” and you go, “Okay, well what’s the concession?” The resolution for the film is the same or higher. It’s not half the number of shots or anything. It’s a situation where, if this had been a theatrical release, the visual effects budget would have been double. So it felt like a real achievement.

Was it always the plan to present Chip and Dale as 2D and 3D CGI characters, respectively?

It was. When I first joined the film, before it was a green-lit and it was just basically Akiva and me — there were producers in the background and writers, of course — we did a proof of concept, about a minute long, and it was basically to show Dale as 3D and Chip as 2D next to each other. It was created to figure out whether it was going to work.

How quickly did you get approval to go ahead with that plan?

I think we finished the proof of concept in October. And by the end of December, I was on the film and it was green-lit, so it was pretty fast from finishing the proof of concept to starting pre-production.

How did having hand-drawn animation, stop-motion animation, and so many other types of animation in the same film change your approach?

There was definitely a lot of looking into what those things would look like together. We knew we couldn’t do traditional stop-motion with Captain Putty (voiced by J.K. Simmons), because he’s interacting with Ellie (Kiki Layne, portraying a human character) in real time. For Putty, there was a lot of studying stop-motion and looking beyond the obvious things.

For example, should he have thumbprints that show up and change from frame to frame? If you look at something from Aardman [stop-motion animation studio], you’re not going to see thumbprints because it’s more polished, but we wanted the animation to feel sort of manipulated, so we introduced more elements like that than you might see in a very polished thing.

We also knew there were a number of scenes that were going to be fully CG. For example, with Bjornson (voiced by Keegan-Michael Key), who was sort of a Muppet character, the bigger of his two scenes is a fully CG environment. We were like, “We’re not really going to make him a puppet, because we have to do the scene in full CG later anyway, so we’re going to make him fully CG, too.”

So we met with a group called Puppet Heap, which has some former Jim Henson people who have a lot of experience with Muppets. We had discussions with them about the behavior of puppets, their limitations, what a puppeteer is thinking when they’re doing it, and so on. And then we showed them animation tests as we were going along and got feedback. There was a lot of asking around like that because we really did want this film to pay as much homage to different animation styles as possible.

How did you decide on the best way to handle Chip, since he represents that sort of traditional, 2D, hand-drawn animation style, but also plays such a big role in the film?

Chip was our biggest concern because we knew we couldn’t do fully 2D, hand-drawn animation for him, due to budget and time constraints. We did look into it and got bids, but it would have doubled our effects budget and added a year to post-production. We do have background characters that are traditionally drawn, though, because they weren’t so important editorially as Chip, and it wasn’t a situation where the edit or dialog was changing a lot over time. So we tried to do a bunch of tricks to pay homage to the 2D, hand-drawn stuff where we could.

It feels like you were bringing these traditional styles into the modern effects production environment in some ways…

Yeah. We would have loved to do traditional animation, and people online like to say, “Well, then why didn’t they just do this hand-drawn?” And that’s like saying, “Why don’t we just go to Mars?” You can say that, but there are aspects of filmmaking that just don’t allow it — two of them being money and time.

Were there certain characters or scenes that proved to be more of a challenge than others?

I’m not sure that there were any specific scenes that gave us trouble, because Akiva was very good about planning everything out. We [previsualized] the entire film. Every shot…we had to plan, because we had half the money you would expect to have, with the full expectation that you still want the highest level of quality. We had to make sure we were not wasting money or time.

And with COVID hitting right in the middle of everything, we ended up having a very short shoot schedule. More of it got pushed into visual effects in terms of environments, and I think somewhere between a third and a half of the movie is just fully CG.

That’s surprising, because it doesn’t feel like it’s so heavily CG.

That’s great to hear. Akiva had this idea that he didn’t want it to feel like you’re observing small characters. He really wanted this to feel like a regular buddy-cop movie, and every once in a while, you back the camera out and realize they’re so small. In terms of shooting style and shot selection and framing, it was very much like a Michael Bay film, with that sort of camera work. So we had to do it digitally because Akiva wanted it to feel like we had little, foot-tall cameramen and small cameras.

He did such a good job of policing that and only allowing the reality to come in when he wanted it. For example, when we’re in Monty’s apartment with Putty, there’s a sort of jump-scare when Ellie shows up outside the window. You suddenly realize you’re in a really small apartment building. Before that, you sort of forgot you were in this small world.

I loved when the characters traveled to the Uncanny Valley and acknowledged that particular era in animation. Did you feel like you had to regress to do it justice?

Oh, you definitely do. I was involved in a number of uncanny valley projects myself, so I feel like it’s less making fun of it and more acknowledging that there was a period of time that we, as an industry, had to get through to get to this point. When the proof of concept was done for that scene where they first meet Bob (voiced by Seth Rogen), Akiva kept saying, “No! It has to look worse!” He even started suggesting he was going to go all the way back to something like PlayStation 2-style models for the character.

We eventually got to a place on the proof of concept where he was happy with it, but then we started the actual project and the digital assets had been remade again to be a little more flexible. So the process started all over again. They were too good. I kept telling them, “Akiva is going to kick this back if you don’t dial it down.” But getting artists to intentionally make their work worse is asking a lot of their egos.

This film is such a journey through the history of animation. Did you come away from it feeling like you learned anything new about some animation styles?

I did. So many different people from so many different worlds were involved. The guy who drew Roger Rabbit in our movie had originally worked on Who Framed Roger Rabbit, for example. Having people who could talk about the old days brought a lot to it.

There’s an episode of Rescue Rangers we see right before they have their wrap party in the film and split up. That episode is a made-up episode, but it had to look like one of the original episodes. We brought on this guy Uli [Meyer] who was really old-school and knows his stuff. Akiva has very specific ideas of what he wants, and he’d say, “Could we do this?” And then [Uli] might say, “Well, the old show wouldn’t have the budget for that, so it wouldn’t be done that way. They would’ve cheated a bit, and it would be like this.”

I do want to ask you about something I read right before the interview. Was Jar-Jar Binks really in the film at one point?

He was! Jar-Jar was originally the Ugly Sonic character. There were a number of different points in the script where things changed over the years. With that whole set-up of Ellie seeming like the bad guy, there was a version of the script where she really was the villain. Part of that whole “It never aired in Albany” misdirect was, at one point, an actual clue they discovered. It’s interesting how many things change in the course of a movie.

Glad to have that confirmed! One thing I can confirm is that Rescue Rangers did indeed air in Albany, NY. I know because that’s where I grew up. I even messaged one of the screenwriters about it, who apologized for misrepresenting my city.

[Laughs] Yeah, there were a couple of things that were historically inaccurate, and that was one of them for sure: It did air in Albany.

Glad we can set the record straight!

Disney’s Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers is available now on Disney+ streaming service.