Community, Dan Harmon’s cult classic sitcom about seven students who bond in a college study group, is never far from the hearts and minds of either its fans or its creators. That the tumultuous production would somehow survive for six seasons and a movie was teased as early as season 2 and became a rallying cry for the show’s devoted viewers, whom Harmon has credited for keeping the show going after NBC fired him following season 3 (he eventually returned). Somehow, the show did make it through six seasons, and given the tenacity with which it persevered through low ratings, a revolving door of talent, and threats of cancellation, the movie has become all but prophetic. Indeed, Harmon offered a recent update on its status.

“There is an outline for it,” Harmon told Newsweek. “There’s a product put together and pitched out in the world. I guess that’s how real it is.” Though he added that, given the nature of the entertainment industry and its ever-conflicting schedules, it might happen anytime between “one and eight years” from now. And while it’s a good sign that the cast has also confirmed their desire to participate (during a virtual reunion in 2020), they do remain busy with other acting gigs, especially the show’s breakouts, Donald Glover and Alison Brie.

But even if the stars align and a movie does get made — particularly if it is eight years from now — can Community, a show that began 13 years ago and ended seven years ago, hope to feel relevant again?

Community feels like a time capsule of its era

The age of the characters is one obvious sticking point. Even for a show that took place in a community college (the fictional Greendale, set in Colorado) that specialized in adult education, most of them — Jeff Winger (Joel McHale) Britta Perry (Gillian Jacobs), Shirley Bennett (Yvette Nicole Brown), and Abed Nadir (Danny Pudi) were in their thirties and beyond when the show ended, while Pierce Hawthorne (Chevy Chase) died during the show’s run. Even while it was on, the show struggled to invent reasons to keep them in school. Still, there was always some “Save Greendale” plot or another to get them back around the study room table, and I have no doubt that the writers can invent another.

The larger issue may be that Community is too much a product of its era to harmoniously or logically exist outside it. Some shows date harder than others. Seinfeld felt hopelessly antiquated almost immediately, while M*A*S*H, from two decades earlier, seems classic. Perhaps having fewer real-world touchstones is responsible for that. M*A*S*H almost seems like it takes place in an alternate universe, whereas Seinfeld reeks of the fashions, trends, and sensibilities of the mid-’90s.

Similarly, Community embodies the hope and change Obama years. The show runneth over with the warm feeling of inclusiveness. It unites its characters unabashedly around diversity and is shot through with the liberal penchant for self-criticism. Its run ended before the ugly divisiveness that has characterized the years since, and it’s hard to know if Community could blossom in our current (or some future) environment — or if Harmon could imbue it with the sensibilities that made it so specific, especially given the predilection towards nihilism that he demonstrates in his current show, Rick and Morty.

Its references are both timeless and dated

Harmon is famous for his references. They can be classic, as in the season 2 Community episode, “Critical Film Studies,” that pays homage to Pulp Fiction and My Dinner with Andre (I challenge anyone to find that specific mashup anywhere else). The movies and shows he references often stand the test of time, leading to references that land across generations, as in the season six episode of Rick and Morty, “Rick: A Mort Well Lived,” that pays homage to Die Hard (although ironically the running joke of the episode is that a 17-year-old is too young to have heard of it.)

But while Harmon’s shows embrace the classics, the writing can also be very contemporary, as in a throwaway joke from the season 1 R & M episode, “Close Rick-counters of the Rick Kind,” when Rick makes a crack at the expense of the band Mumford and Sons. While Rick and Morty, a classic for the ages, is sure to enjoy posterity, the Mumford and Sons joke already seems passé.

Community likewise contains many near-obsolete references and plot points, especially when it comes to technology. The characters are always using “cutting edge” tech for the early 2010s that already seems extinct: Facebook, pre-smart cell phones, Blackberries, early apps, and modes of texting. Though much of this tech has developed very recently, it has evolved so exponentially that the show’s attempts to be of its moment feel even more dated.

Story and characters keep fans coming back

So why, then, if Community is such an indelible product of its age, and in some ways so dated, why is it so re-watchable, so easy to come back to? For one thing, it contains multitudes. The stories are told in many different genres and styles that when watching them over a couple of weeks or months, or even bingeing them outright, they don’t feel like a parade of copies.

A few examples of the great stylistic diversity among the episodes include the Goodfellas homage, “Contemporary American Poultry;” the mockumentary-style “Intermediate Documentary Filmmaking;” the bottle episode, “Cooperative Calligraphy;” the brilliant Law and Order parody, “Basic Intergluteal Numismatics,” in which Jeff and Annie Edison (Brie) try to unmask the “ass-crack bandit;” and the fake clip show, “Paradigms of Human Memory,” which I’m guessing inspired the fake R&M clip show, “Morty’s Mind Blowers.”

But the variety of genre and story types are never just gimmicks. They are always in the service of highlighting characters who are flawed, not always nice — or even good — people. It all starts with Jeff Winger, the hardened guy pretending to be a shallow nihilist who can’t hide how deeply he cares. It’s a classic character type, and I don’t think McHale, playing the straight man, has gotten enough credit over the years for grounding the show so well (it’s a hard cast to stand out in, but still). Playing a part-time lawyer and full-time manipulator, the actor had to make a lot of speeches and he lands every one. It’s easy to see why the other characters look to Jeff for leadership, even as he looks to them for the moral guidance he never got from his parents.

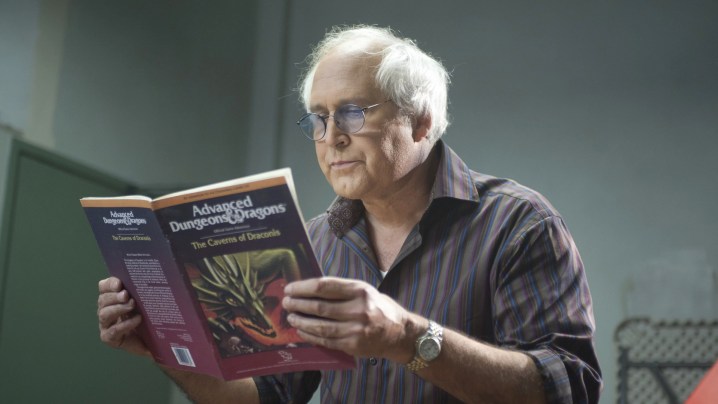

Jeff and the others have an uneasy relationship with Pierce Hawthorne, the antagonistic tycoon played by Chase. Though Pierce is not quite the show’s villain (that role is played by Ken Jeong as the deranged lunatic, Ben Chang) it seems as though the study group’s exasperation with him mirrors some of the real-life dynamics between Chase and the other actors behind the scenes.

Given his reputation, I don’t doubt Chase chafed at his castmates. But he doesn’t seem to mug (more than usual) or try to take over scenes, even though he played leads for almost his entire career and was by far the most famous of the ensemble when the show started. He embraces the sitcom staple of the endearing jerk who tries too hard (think John Larroquette in another NBC classic, Night Court), but who the group accepts despite his many shortcomings.

The group also takes some time to warm up to Abed Nadir (Danny Pudi), the autistic character of Palestinian/Polish descent who eventually became the show’s heart. The character — and Pudi’s pitch-perfect performance — provide a calm center around which the hijinks, shenanigans, and emotional turmoil can rage. As Abed himself notes, he is the Spock or the Data of the group, unable to pick up on social cues, but learning how to react and have relationships through a careful study of human behavior. Indeed, Abed sometimes takes on the role of documentary filmmaker, observing his friends with almost anthropological detachment.

As with the famous characters he evokes, Abed’s moments of human connection are profoundly satisfying for viewers. The way he is represented is also gratifying, especially through his friendship with Troy Barnes (Glover). Troy starts off as a typical jock in season 1, but eventually lets his guard down and his inner nerd out. Over time, the bond between Troy and Abed became one of the most endearing and entertaining on television, while doing important work challenging and subverting stereotypes about Black and Arab men.

One of the best “found family” shows

Embracing Pierce and Abed as part of the gang despite their tone deaf offensiveness characterizes the main appeal of Community which is that its one of the most affecting shows ever about found family, that tried and true format in which lonely people of disparate backgrounds bond intensely while contriving to be together all the time. It’s a fantasy of unconditional love and acceptance that feels especially empowering because it suggests we can find our kindred spirits, rather than being stuck with people who may not appreciate our innate specialness. In this way, Community can feel intensely soothing (the show helped get me through two soul-shredding breakups in the last decade).

As the show goes through the typical “will they or won’t they” with different characters over the years, it also provided that staple of the sitcom: romantic wish-fulfillment. Community never shied away from sexy fantasies and often fetishized the bodies of its stars. McHale, with his action hero body, shows the most skin throughout the series. He often has his shirt off and sometimes even his pants. Dean Craig Pelton (Jim Rash) and Troy both show off fit bodies as well, while Britta and Annie wear tight sweaters and show lots of cleavage.

It’s hard to say how much of this would fly in today’s cultural environment, and despite its progressive sensibilities, the show is problematic at times. There are a lot of gay jokes. Yes, they are typically used to skewer Pierce as an out-of-touch bigot, but they still exist to get easy laughs. The way the show treats queer characters might feel a little more balanced if Dean Pelton didn’t keep his sexuality under wraps (in one of the few bad episodes, “Basic Rocket Science,” he is seen as possessing a map that highlights truck stops and park bathrooms). The word “slut” is also thrown around, and Britta especially is highly sexualized while also being a bit too much of a punching bag for the other characters for her promiscuity (among other reasons).

Given all this, can Community fulfill its self-proclaimed mandate to conclude with a movie that doesn’t feel entirely past its sell-by date? One TV comparison point might be Veronica Mars, another fan-obsessed show with a warm cast and a self-contained universe that went off the air a few years before Community premiered. While the 2014 film that was made from a fan-driven Kickstarter campaign was satisfying for fans (including me), it didn’t quite capture the show’s original magic. Though perhaps whether a Community movie gets made isn’t that crucial if revisiting the original can continue to yield so many returns for those who have found family within it.