Ahead of the 91st Academy Awards on Sunday, our Oscar Effects series put the spotlight on each of the five movies nominated for “Visual Effects,” looking at the amazing tricks filmmakers and their effects teams used to make each of these films stand out as visual spectacles.

It’s no small task to bring one of mankind’s most famous achievements to the big screen and do it justice, but that’s exactly what director Damien Chazelle did with First Man, 2018’s biopic of Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong, who’s best known for taking “one small step” on the surface of the moon that would resonate throughout human history.

Chazelle and a team led by Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor Paul Lambert (Blade Runner 2049) used a unique combination of miniatures, archival footage, traditional digital effects, and massive LED screens to re-create the Apollo 11 mission and the events leading up to it, and the end result is a film that makes the landmark moment in 1969 feel as powerful today as it did half a century ago.

Digital Trends spoke to Lambert about the innovative techniques that allowed the First Man visual effects team to blend old footage and era-appropriate camera aesthetics with modern, cutting-edge filmmaking technology, and draw from one of mankind’s greatest achievements to deliver one of 2018’s best movies and bring home an Academy Award for the film’s visual effects team.

Digital Trends: During your early meetings with Damien Chazelle, what were the discussions like as far as how he envisioned the role of visual effects in the film and what you proposed doing?

Paul Lambert: Damien was very adamant that he didn’t want the visual effects to take you out of the story. He wasn’t interested in doing green screens and blue screens. He always wanted to find a location we could augment in post-production rather than having an actor in a partial set with blue and green screens.

“We eventually decided that with anything that was a mid-shot or a close shot, we would try to use 1:6 scale miniatures.”

We ended up testing an idea in which we put computer-generated graphics on a big LED screen and then filmed it with the production film cameras. What we found was that it actually worked surprisingly well, because if you were to try and do it with a digital camera — like one of the more modern cameras — you would actually end up seeing a lot of the pixelization because of the resolution of the screen and the size of it.

We were using a film camera, though, and film automatically adds grain, which actually helped disguise the fact that it was a pixelated image on the LED screens. So we were able to keep a lot of the backgrounds in-camera for the film.

How did using these large LED screens affect other elements of your approach to the film’s visual effects?

Unlike with a green-screen shoot, using the LED screen lets you get all of the interactive light and all of the reflections from what’s on the LED screens on your actors and the set itself. With a green screen, you would have to do that in post-production. Damien wanted such a practical push to everything, and [by using the LED screen] we were able to keep all of the characters’ visors on. That’s something else you don’t usually do. You typically take off their visors, then replace the visors digitally.

Obviously, there were times when we’d see the crew in the visors and we would take them out digitally in post, but what you gain from getting the original reflection from the content on the LED screen is so much better than if you try and do it all as a post-process afterwards.

How did miniatures factor into the emphasis on practical effects?

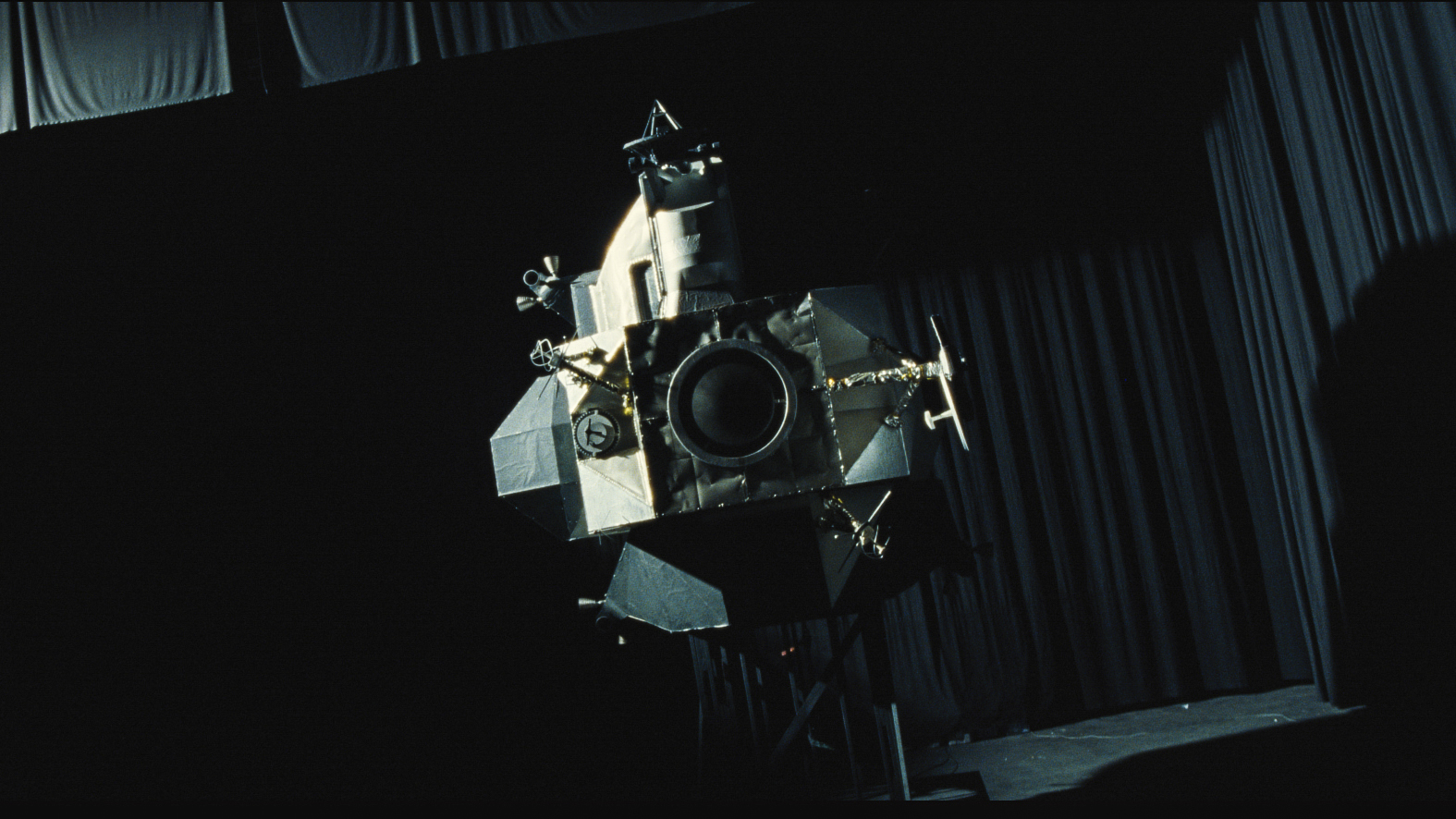

We talked early on about wanting to use miniatures, because when you look at some of the archival footage, the light out in space from a single-point source makes it all look like miniatures already. We eventually decided that with anything that was a mid-shot or a close shot, we would try to use 1:6 scale miniatures. These were built by Ian Hunter, who also worked on Interstellar. He had a lot of experience with space photography already, so he was brought on board.

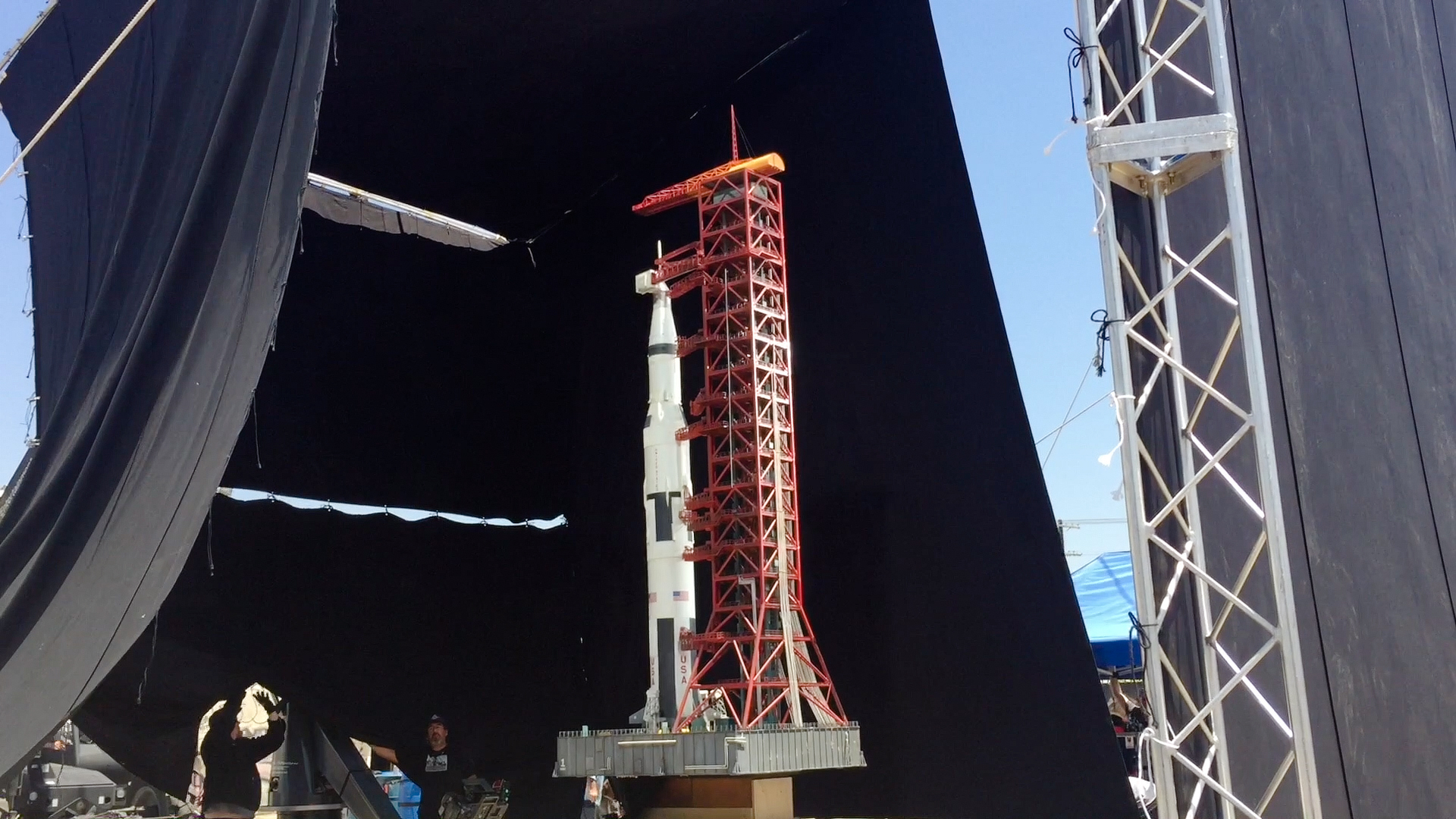

We did all of the docking with miniatures and we also made a 1:30 scale version of the Saturn V. That thing stood about 14 to 15 feet tall and was used for some of the [Vehicle Assembly Building] scenes. When the rocket is coming out of the VAB in the film, that’s actually a miniature.

With production deadlines, we did have a bit of mixing and matching with miniatures and CG. We actually shot the [Lunar Excursion Module] on stage, but because the legs are so big on the LEM, we had to put them in digitally.

What went into creating the climactic moon landing scenes?

When we got to the moon, it was decided that we would try to shoot that in a quarry. The art director, Nathan Crowley, found one outside of Atlanta and he dressed five acres to look like the area where they had landed on the moon. This was an active quarry, so there were mounds all over and there were cranes and all sorts of things everywhere, so part of the process was to clean all of that up and extend it out as if we really were on the moon.

“Damien wanted to keep it as true to the era and to the photography and film footage of the Gemini missions and the Apollo missions … “

We had a crew of around 100 people on set, and we had tents everywhere, and this great big IMAX camera, too. Every time you saw the actors’ visors, there was a bunch of stuff in there that we didn’t want in the movie. Usually you would just replace the entire visor digitally, but because there is such a complexity to the reflection that we wanted to keep, we only cleaned up the areas which we needed to clean up. It takes a longer time to do it this way, but the result you get is far superior.

The last thing you want is for the moon landing to look staged …

Exactly. Having such a large crew in an area where you’re not supposed to see footsteps from any other people created a lot of work. The art department did a fantastic job of cleaning it all up each day, but once you get those early scans in, you start to see a footstep here or there, or a scrape on the floor which obviously shows that something human has been there already, and that really is the last thing you want. There was a fair amount of work on the those sections to clean it up and keep it as realistic as possible.

With First Man, you were in a relatively unique position of having a lot of real-world archival footage of the events depicted in the film. How did archival footage and real-world, historical resources play into the film’s visual effects?

We had access to a lot of archival material, which was great. Damien wanted to keep it as true to the era and to the photography and film footage of the Gemini missions and the Apollo missions, and from the X-15 as well. We were originally planning on replicating the entire Apollo launch using miniatures, but as we got more and more archival footage, it dawned on me that perhaps we could use the odd shot here and there from the archival footage if I could treat it and clean it up so that it fit with the production footage.

So I pitched that idea to Damien. He was adamant that if the audience realized they were watching archival footage, you’d lose them, so there was additional pressure for us to make sure that our technique worked.

Part of our process was to speed up the slow-motion archival footage, clean it up, take out all the scratches, take out all the additional grain, and make it as clean as possible. At that point, if you cut it into the movie, it would actually pop out for being too clean. Once we reached that particular stage, we would degrade it so that it fit with the 16 millimeter and 35 millimeter footage of everything else surrounding it.

You were working with archival footage that’s more than half a century old, in some cases. Did that pose any unique challenges?

Well, as we pulled this archival footage, we came across some that had been in film cans since the Apollo launch. Every launch has a series of engineering cameras focused on particular areas, but because most of these launches went smoothly, this footage was never really seen.

More Oscar Effects Interviews

- How ‘invisible’ effects brought Winnie the Pooh to life in ‘Christopher Robin’

- To drive its giant virtual world, Ready Player One needed a custom A.I. engine

- How big screens and small explosions shaped the VFX of Solo: A Star Wars Story

- How Avengers: Infinity War’s Oscar-nominated VFX team made Thanos a movie star

Some of it was on film stock you couldn’t actually play back any more, because it was on 70 millimeter NASA military stock, and there just weren’t any machines that you could play this back on. We spent months trying to find a way to scan it [and] finally found somewhere in London that had this experimental scanner. It was truly phenomenal.

There’s a shot in the movie where you see the Saturn V igniting. It’s a wide shot and you see the Saturn V in the center frame and you see two big plumes of smoke shooting out from the sides of the rocket. That’s actually original 70 millimeter footage of the Apollo 14 taking off. It’s the original footage cleaned up by us in the center frame, and we then extended each side of it with CGI to give it a more cinematic framing.

We did a lot of this on a number of shots in that sequence, because the engineering cameras weren’t framed for the cinema. They’re more of a square format. So we would take this footage, place it in the center, and then extend it with matte painting or with additional CG of the rocket or other CG effects.

Damien Chazelle is known for his approach to music and sound in creating his films. Was that something that factored into your creative process on the visual effects side?

When I joined the film, Damien sent me what we called “The Notebook.” It was like a 300-page PDF of the entire movie, with his thoughts on how he wanted certain visuals, how he wanted certain colors, and how he wanted certain sounds and music, as well.

We didn’t have any of the usual pre-visualizations, but he had created a cut of the film that used storyboards and archival footage to indicate how he wanted the launch or the docking to look. It used real footage, and what really blew me away was that he actually had the music cut into those sequences already. I’ve never experienced that before. What you see in the movie now is the same tune which I heard back in July 2017.

You won a well-deserved Oscar for your work on Blade Runner 2049, and now you’re back with Denis Villeneuve on Dune. Was it easy to shift back into that more fantastic, sci-fi environment after working on such a grounded-in-reality film like First Man?

It’s funny you should ask that because there is a similar trait to both directors. They’re both visionaries. When you talk to them, they have the movie in their head already. On a number of occasions, I’d be on set for Blade Runner or First Man, and I’d be pondering something on the screen, and either Denis or Damien would see me at the monitor and come and talk about the frame I was looking at, and I would always end up thinking, “Oh, okay, this is why you’re the director. You see all of this with just one, single frame.” It’s absolutely inspiring.

First Man premiered October 12, 2018. The film was awarded an Oscar in the Best Visual Effects category at the 91st Academy Awards ceremony, which was held February 24.