As Pride Month continues, we celebrate Kristen Stewart, an important contemporary icon whose career — while certainly not just beginning after two decades in the movies — is still well on the rise at 32. Certainly, she’s changed the conversation in crucial ways by occupying an important historical niche that perhaps no other LGBTQ+ actor has achieved: She is an out queer movie star who has appeared in many queer-themed films, including The Runaways (2010), Certain Women (2016), Lizzie (2018), J.T. Leroy (2018), and Happiest Season (2020).

Even when she doesn’t embody queer characters, her choice of roles takes her into territory well understood by the LGBTQ+ community; that of the dispossessed and marginalized, misfits and outcasts who suffer the emotional toll of identity crisis and of not being accepted by family, friends, and/or society. Surely this was part of the appeal of Twilight, and must account for her attraction to biographical roles such as Seberg (2019) and Spencer (2021), her extraordinary Oscar-nominated portrayal of an emotionally distraught Princess Diana.

Historically, positive queer representation is rare

Still, it took us a long time to get here. The history of queer representation in Hollywood is a shameful one indeed. The Hollywood Production Code forbid same sex desire or unconventional gender presentation or identity (save for exceptions such as drag comedies), and even as the code ended and Hollywood became far more radical in the both the themes and the content it handled in the late 1960s, queer characters were still mostly taboo. Even the rare film that tackled such material at the time, such as Midnight Cowboy (1969), earned an ‘X’ rating, reinforcing the misconception that homosexuality was socially and morally aberrant.

Even on the cusp of a new century, it was an enormous deal for Ellen DeGeneres to come out in 1997, along with her girlfriend at the time, Anne Heche. Both actors’ careers suffered for it. Even well into the 21st century, when LGBTQ+ characters finally began to appear in American movies in a more sympathetic (rather than villainous) light, straight actors usually played them and were acclaimed for their “bravery” and their astonishing “range:” Tom Hanks in Philadelphia, Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto in Dallas Buyers Club, Penelope Cruz in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Greg Kinnear in As Good as It Gets, Hilary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry, Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in Brokeback Mountain, Sean Penn in Milk, and the list goes on.

Both Hilary Swank and Tom Hanks have recently conceded that trans and gay actors, respectively, should have played their roles, with Swank saying, “We now have a bunch of trans actors who would obviously be a lot more right for the role and have the opportunity to actually audition for the role.” Hanks expressed similar sentiments: “Could a straight man do what I did in Philadelphia now? No, and rightly so…We’re beyond that now, and I don’t think people would accept the inauthenticity of a straight guy playing a gay guy.” One hopes that both statements are true, but then Hollywood, despite its avowed progressivism, often seems to be at least a decade behind the times both on and off screen.

Challenging stereotypes from the beginning

Which brings us back to Stewart. We hear all the time that representation matters. But in her case, both she and the movies she’s in practice what they preach. A queer person playing queer — both often and in high profile productions — is still a rare event indeed, especially in the movies (TV, with its lower financial stakes, has been quicker to change). Yes, it’s true that Stewart only officially came out five years ago, but few would suggest that her queer roles before coming out somehow “don’t count” because she was still publicly identifying as straight, especially since she has always been a friend to the queer community.

Indeed, her films form a cohesive body of work that represents a spectrum of queer characters of all different stripes. She not only gets to play gay, but she’s also avoided doing it as any one particular kind of gay character, which is the best way to challenge stereotypes, especially for viewers who need their horizons expanded. And when she’s not playing an outwardly queer character, her characters often seem ambivalent about gender and sexuality. She seems to be saying, Dude, I’m me. Don’t worry about the rest.

The genesis of all this was evident in her first major role in David Fincher’s vastly underrated thriller, Panic Room (2002), in which she plays the 11-year-old Sarah who moves with her mother (Jodie Foster) into a cavernous brownstone on the Upper West Side. Sarah is what some might consider a “tomboy,” someone with little interest in the stereotypical activities of girls her age. Playing the character this way was no minor choice just after the turn of the millennium when highly sexualized stars like Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, and Paris Hilton, among many others, dominated a mainstream media still firmly driven by the male gaze.

In Panic Room, Sarah rolls through the apartment on a scooter and bounces a basketball, rocking the androgynous look that Stewart would ease in and out of as she got older. Of course, one should never expect to move into a house with a panic room without being expected to use it, and so she and her mother soon find themselves fending off three home invaders. Far from being a shrinking violet, Sarah rises to the occasion to help protect home and family. It’s also notable that Stewart plays a heroic person with an impairment in this film (her character has diabetes).

Twilight and negotiating superstardom

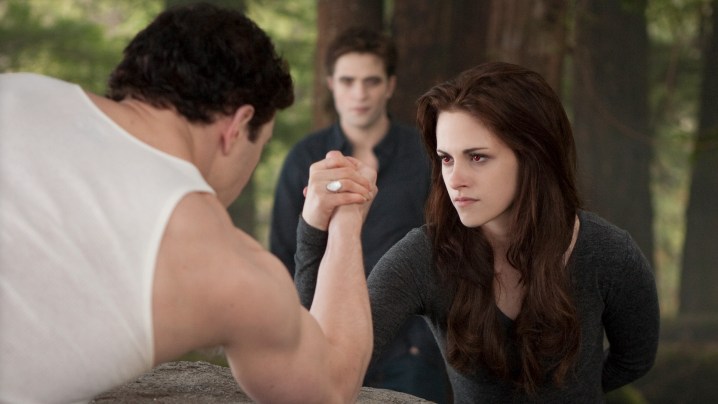

Foster didn’t believe that Stewart would continue acting, figuring her interests lay more in directing. But not only did Stewart continue, she’s been prolific. In just six years between Panic Room and her global star-making role in Twilight (2008), she appeared in fourteen films, perhaps most memorably as the teenager who develops a crush on doomed hitchhiker, Christopher McCandless (Emile Hirsch), in Sean Penn’s Into the Wild (2007). Although her role as someone visibly manifesting hetero desire is an outlier for her career, with another obvious exception being Bella Swan, the pale, trembling lass caught between supernatural hunks (Robert Pattinson and Taylor Lautner, in case anyone somehow doesn’t know) in five Twilight movies that became enormous global hits.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the success of the gothic melodramas, and the massive fanship — both gay and straight — she accrued along with it, everything aligned to potentially destroy not only her career, but her personal life as well. She was young, a tabloid obsession, and the heart of a billion dollar franchise that sprung 40 gazillion fan and slash fiction tales (I counted). Even the heartiest of souls might be destroyed by the onslaught of global attention, and she certainly suffered her share of abuse in the media. She also risked being typecast — or worse, not being cast anymore at all given her identification with the role, not to mention how radioactive she had become in the cruel and unforgiving celebrity press.

Part of the way she negotiated her way through the Twilight movies was to push the boundaries of where audiences would accept her even while she was making them. This included using her star power to take on queer-positive roles, such as her performance as the young Joan Jett in The Runaways, which chronicles the musician’s early career and her struggles to forge an all-girl rock band (basically unheard of in the mid-1970s) in one of the most unapologetically misogynistic industries imaginable. The movie also dramatizes Jett’s relationships with women, as well as her insistence on appearing as a more traditionally male rock figure.

The Runaways is a standard rock biopic save for the fact that it thrums with both queer and female desire. Though Stewart was still not yet publicly identifying as gay, there’s a looseness in her performance, a comfort in the material that conveys the sense of self-possession Jett herself had strutting the un-self-conscious glam, tough-girl style that made her a queer fashion icon. Stewart has become quite the queer fashion symbol in her own right, and the most exciting creative sequence in a film full of rock performances is when Jett makes a homemade Sex Pistols t-shirt with scissors and black spray paint (Stewart’s character in Panic Room likewise wears a t-shirt emblazoned with Sid Vicious). You can feel the character’s transgressive joy in an act that’s simultaneously expressive and subversive, flipping the bird to patriarchy, capitalism, and a clutch of other repressive institutions. It’s an act born of a pure punk ethos and it could symbolize Stewart’s career.

Post-Twilight success

Along with Twilight co-star and former boyfriend Robert Pattinson, Stewart has since shown a distinct lack of interest in big budget franchise pictures, Snow White and the Huntsmen (2012) aside. She’s always been drawn to edgy and iconic directors. Her appearance in David Cronenberg’s recent film, Crimes of the Future (2022) is just one example. Her participation in Woody Allen’s Café Society may seem problematic now, but she got in on the tail end of the era when Allen could help legitimize an actor’s career just by casting them. And whatever you think of him or the film, she’s luminous in the part.

Two of her best performances and most interesting roles came in a pair of films by French director Olivier Assayas, Clouds of Sils Maria (2014) and Personal Shopper (2016). Assayas is an effortless poet of edgy cool in work like Irma Vep, Demonlover, and Carlos, and effortless cool is what Stewart projects, especially in Personal Shopper, a ghost story of sorts in which she plays a young American who scoots around Paris on a motorbike, wears leather, and smokes cigarettes. Ironically, she would later go onto play Jean Seberg, an American actress who became an icon in an immortal French movie, Breathless, but here she is the icon. As is typical for a Stewart performance, she eschews conventional standards of feminine beauty and is all the more captivating for it. But she is doing far more than just posing. As she later would as Diana, she plumbs the depths of grief, disassociation, and ennui in a performance that The New York Times called “exceptional.”

Finally, Stewart has been instrumental in helping to stretch the kinds of genres in which queer characters can appear. Holiday movies are among the most conservative of genres, their focus almost entirely on traditional notions of home and family, which is why the lesbian Christmas movie, Happiest Season, was the cause of much yuletide joy among the LGBTQ+ community (along with some complaints). Stewart has also kicked butt in a pair of recent action flicks, Charlie’s Angels (2019) and the sci-fi Underwater (2020), helping expand representation in a genre that sorely needs it.

As to the burgeoning cultural discussion of whether only queer actors should play queer roles, Stewart believes it’s a slippery slope. “I mean, if you’re telling a story about a community and they’re not welcoming to you, then f*** off,” she said in an interview with Variety. “But if they are, and you’re becoming an ally and a part of it and there’s something that drove you there in the first place that makes you uniquely endowed with a perspective that might be worthwhile, there’s nothing wrong with learning about each other.” Sounds like a perfect way to sum up the cinematic journey of the queer icon thus far. Can’t wait to see where she takes us next.