Lorcan Finnegan has a lot to say about the negative effects of capitalism and consumerism. In his 2019 feature Vivarium, Finnegan uses a young couple buying a house in a suburban neighborhood to represent how capitalism drives people to follow societal norms and get stuck in life’s mundanity. Finnegan explores capitalism once again in his new film, Nocebo, but frames his discussion through the wealth divide between the rich and the poor.

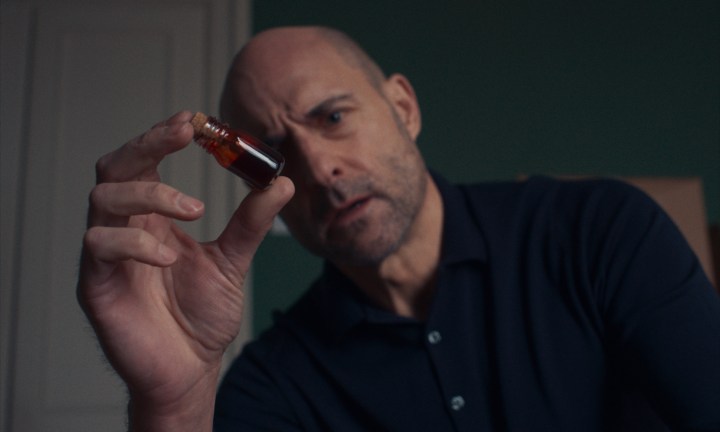

Eva Green stars as Christine, a fashion designer plagued by a mysterious illness that limits her abilities to work and form relationships. When Diana (Chai Fonacier), a Filipino nanny, begins to aid Christine with her illness, the traditional healing methods work. As Christine relies on Diana for more help, her marriage with Felix (Mark Strong) suffers, throwing their family’s well-being in jeopardy. The psychological thriller is a fascinating examination of the placebo and nocebo effects and a staggering commentary on consumer culture.

In an interview with Digital Trends, Finnegan discusses nocebos, capitalism, Eva Green, and how a connection between Filipino shamanism and Irish folklore inspired his latest film.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Digital Trends: After I watched the film, I went to my kitchen. I go to turn on the faucet and I see this bug crawling up the wall and I’m like, “You got to be kidding me with the bugs.” I killed it so fast. I wasn’t taking any chances.

Lorcan Finnegan: [Laughs] I kind of keep forgetting about that element of the film, actually.

No more bugs for me. I want to know what first inspired your curiosity about nocebos and the nocebo effect.

I read a book actually called Sleep Paralysis: Night-mares, Nocebos, and the Mind-Body Connection. It’s by a medical anthropologist, Shelley Adler. It was just an interesting area. Garret [Shanley], the writer that I work with, read the book as well, and we started just researching placebos. They’re the opposite of nocebos. Our research kind of brought us to the Philippines, weirdly. As we delved into it, we kind of realized that placebos were related to shamanism, and so were nocebos.

Ireland had a tradition of folk healing, you know. These powerful women in society are called wise women. That kind of got eradicated with the arrival of Christianity, and then later with being colonized by Britain. As we looked more into shamanism and contemporary shamanism, it still exists in the Philippines, particularly in Cebu, an island, and Siquijor, an island beside Cebu. So we started looking into that more and started drawing these connections between our [Irish] folklore and their folklore of the Philippines, which is weirdly connected even down to very specific stuff.

We went to the Philippines to explore more. Obviously, the Philippines was colonized by the Spanish about 10 years before Ireland was colonized by the British. They introduced Christianity, and they kind of wiped out these powerful healing women called the Babylon. When we went to the Philippines in 2019, we visited witch doctors, practitioners of Kulam, which is like black magic, and tribal chiefs.

We could understand it more fully and started seeing this other relationship that was kind of connected, which is creating the story between the eradication of these sorts of nature-based beliefs and capitalism and colonization. They’re all kind of connected.

Now, countries in Southeast Asia, particularly, are still kind of colonized by the West and exploited by them in a new neo-colonial sort of way. So we thought that was an interesting way into our story, and that’s sort of that’s how it began. It’s a long way to getting into it. [Laughs]

You touched on the themes of capitalism and consumer culture. You’ve tackled those themes in previous films. In Nocebo, you see the divide between the wealthy and the poor. Why do you continue to explore these themes in your films?

Interesting. Well, I mean it’s one of the problems with humanity. It’s one of the biggest causes of all sorts of strife and war and everything. This sort of massive divide between the wealthy and the poor. It just keeps on growing and growing. Yeah, I think that kind of injustice just generally pisses us off, and that, in turn, is a provocation to make work.

Eva is fascinating in this film. For her previous choices in big-budget and genre films like the James Bond movie Casino Royale, she always goes for it. That’s the best way I can describe her performance. How would you describe Eva?

Yeah, she’s incredible. She’s an amazing actor and completely commits. For Eva, as well, in this story, the themes that we’re exploring, she’s quite politically minded. She thought it was important for her to kind of get stuck in, even though she’s playing an unsavory character. [Laughs]

It’s a challenge.

Yeah, exactly. She’s great. She’s cool to work with.

As good as Eva is, the performance that will stick for most people is from Chai. I think other people will have that reaction as well. During the casting process, what traits were you looking for to fill that role, and how did you come to select Chai?

Well, it was interesting. After we went to the Philippines and all that and decided to kind of go for it with this story, we pitched the project in Macau, China. We got these co-producers on board from the Philippines and at Epic Media. We could understand the nuance of culture a bit more, but we still wanted to make sure we got it right so we brought on this writer, Ara Chawdhury from Cebu.

Our character was then based in Cebu. We had to find a Cebuano–speaking actor. I really wanted to make sure that they were a genuine representation of a Cebuano woman. We didn’t have a massive pool to start looking in. Our co-producers in the Philippines worked with Chai before, and they suggested her and so did Ara.

We did see probably like 15-20 people for the role over Zoom because it was all COVID stuff going on. She [Chai] was just brilliant. I think she just nailed this balance between being very friendly and slightly submissive. Also, being able to be quite dominant and threatening as well.

She did this amazing thing in the audition where she would disarm you with a smile. She’d say something that could be taken as being a bit weird but then give a lovely, big, warm smile afterward. You don’t really know how to take it. That’s where we began developing that character.

She has these two sides to her. As the flashbacks start to increase, it almost becomes her move. It’s like she switches roles with Christine. Was that a conscious decision you made in the writing process?

Yeah, that was the real challenge, and that’s what we set out to do in the film, to do a placebo and nocebo with the story. So like switching allegiances halfway through the story. What you think is good could be bad or what’s bad could be good. That was the intention.

There are so many close-ups and visceral images, I think of the dog and the fire. They’re both terrifying and beautiful in a strange way. Why did you decide to shoot these images with a close-up?

Yeah. I mean. I sort of developed the project over a long time so it’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment we went, “Oh yeah, use lots of close-ups.” Me and the DP, Radek [Ladczuk], we’re talking about various films. Bergman’s Persona was actually an influence in terms of close-ups.

We shot in a 1.66:1 aspect ratio, which is a little bit tighter because we knew we had two characters that were going to be quite close together. We wanted to bring them close, which was a lot of two-shot portraits as well as close-ups. You get close to the characters and get to feel you may know them through close-ups, but being subverted as the film progresses.

You feel a sense of claustrophobia.

Yeah. Also, I love portraiture in photography as well. Sometimes, a good close-up can really get a different sense of the person rather than just a broad sense of them. You can really see their face, and you can see the nuances in their expression.

Nocebo is now in theaters. It will be on demand and on digital on November 22. The film will stream on Shudder at a later date.