The Midnight Club may have been made with a very different target audience in mind than most of Mike Flanagan’s films and TV shows, but it still fits snugly within the writer-director’s existing filmography. Not only does the new Netflix series, which Flanagan co-created and executive produced with Leah Fong, bear a striking visual resemblance to many of his previous projects, including the Stephen King adaptation Doctor Sleep, The Haunting of Hill House, and Midnight Mass, but it’s also deeply, unwaveringly earnest. It pulses with the same earnestness, in fact, that is present in practically every one of Flanagan’s past film and TV offerings.

Up to this point, Flanagan’s commitment to taking the horror genre as seriously as he can has both paid off in spades and made his attachment to authors like Stephen King unavoidably clear. In The Midnight Club, however, that earnestness has never felt more earned and never been quite as distracting. The series, which is based on the horror novel of the same name by author Christopher Pike, chooses more often than not to face everything that happens in it with as straight a face as possible — even in the moments when a knowing smirk is deeply needed.

That’s not to say that The Midnight Club isn’t just as entertaining or well-filmed as all of Flanagan’s past Netflix offerings. On the contrary, the YA series looks just as good as, say, The Haunting of Hill House or The Haunting of Bly Manor, and it boasts the same ability to make you jump out of your seat basically whenever it wants. But The Midnight Club is also a more structurally ambitious project than any of Flanagan’s previous Netflix shows, and it doesn’t always manage to ride the difficult tonal line that is at the center of its first season.

A strong premise

The Midnight Club is, in many ways, tonally lighter than any of the other Netflix shows that Flanagan has produced over the past few years, though, its premise certainly doesn’t suggest that. The series, which drops in its entirety on October 7, follows a group of terminally ill teenagers and young adults who check themselves into an oceanside hospice known as Brightcliffe. Once there, the hospice’s residents all strive to carry on the decades-long Brightcliffe tradition of meeting in the house’s library every night in order to tell each other scary stories. It’s this tradition that binds Brightcliffe’s residents together as a group known only as “The Midnight Club.”

Being a part of The Midnight Club doesn’t just mean that its members have to agree to tell and listen to each other’s scary stories, though. The club’s members also swear an oath that, after they die, they will each try to send a sign to their surviving friends letting them know whether or not there really is an afterlife waiting for them on the other side. It’s this latter detail that opens the door for The Midnight Club to fully reckon with the fear of death that is hanging over every one of its terminally ill protagonists.

It’s also what allows The Midnight Club to emerge as a thematically fitting new addition to Mike Flanagan’s growing filmography. Despite boasting the kind of melodrama and unrepentant earnestness that makes its YA roots impossible to forget, The Midnight Club is ultimately just as concerned with the inevitability of death as The Haunting of Bly Manor and Midnight Mass. However, unlike those shows, The Midnight Club is less interested in murder and ghosts as it is in stories, and the ways in which people use storytelling to both escape and accept their own deaths.

Scary stories to tell in the dark

The Midnight Club uses the late-night stories its central teenagers tell each other at night to both explore that theme and to routinely experiment with the form, style, and structure of the show itself. Each one of the stories that are told in The Midnight Club is not only based on a pre-existing novel by Christopher Pike, but is also distinctly different from the rest. A story told by a religious young girl named Sandra (Annarah Cymone), for instance, is a black-and-white homage to the pulp detective stories of the 1940s, while another is a WarGames-esque sci-fi story about video games, time travel, and preventing the apocalypse.

Some of the show’s stories predictably land better than others, but it’s when The Midnight Club is embracing its semi-anthological format that it is at its most fun, playful, and self-aware. Each one of the show’s short stories injects it with a renewed jolt of energy that helps keep The Midnight Club moving forward — especially throughout its first half. The problem is that the series also attempts to split its focus between the nightly storytelling meetings that its central characters indulge in and the mysteries about Brightcliffe and its history that lured The Midnight Club’s lead heroine, Ilonka (Iman Benson), to the oceanside hospice in the first place.

While several of Brightcliffe’s mysteries do initially seem interesting as well, the truths behind many of them end up coming across as lackluster or misguidedly silly. The hospice’s ties to ancient Greek teachings and rituals, for instance, never quite manage to feel as creepy as The Midnight Club wants them to be, and the few ghosts that seem to haunt Brightcliffe’s halls are explained away in disappointingly nonchalant fashion near the end of the series’ first season. The show’s central, season-long mysteries are, in other words, so lackluster that you’ll likely find yourself wishing The Midnight Club had shed itself of them in order to spend more time indulging in its titular group’s short story sessions.

A deadly serious plot

Similar to its structural issues, The Midnight Club also struggles to find the right balance between the kind of playful, self-aware genre experimentation present in its short story segments and the earnestness that has become so prevalent in Flanagan’s work. While it makes sense for the show’s terminally ill characters to be asking the kind of questions about life, death, and fate that they frequently do throughout The Midnight Club’s 10-episode first season, the series also makes the mistake of using its characters’ shared situation as an excuse to treat everything with the utmost seriousness.

Even the show’s silliest moments are handled with a level of straight-faced earnestness that feels misplaced, and certain cliché YA storylines, like Ilonka’s growing attraction to Kevin (Igby Rigney), another of one of Brightcliffe’s young residents, are handled with a level of solemnity that drains them of any kind of dramatic or romantic spark. The series is, therefore, at its best when it’s able to ride the line between earnest and self-aware, as it frequently does in its most emotionally compelling episode, which somehow manages to end with a beach performance of Green Day’s “Good Riddance” that doesn’t feel nearly as suffocatingly saccharine as it sounds.

A talented cast

The Midnight Club’s stars all shine in their respective roles as well. For her part, Benson brings a warm, charismatic presence to the series as Ilonka, the series’ lead and go-to vessel for exposition. Chris Sumpter also turns in a compelling and moving performance as Spencer, a gay patient at Brightcliffe who is struggling to come to terms with the disappointment and bigotry he’s had to face throughout his life. Meanwhile, outside of its young stars, frequent Flanagan collaborators like Zach Gilford, Rahul Kohli, and Robert Longstreet all make memorable supporting turns as some of the adult faces of The Midnight Club.

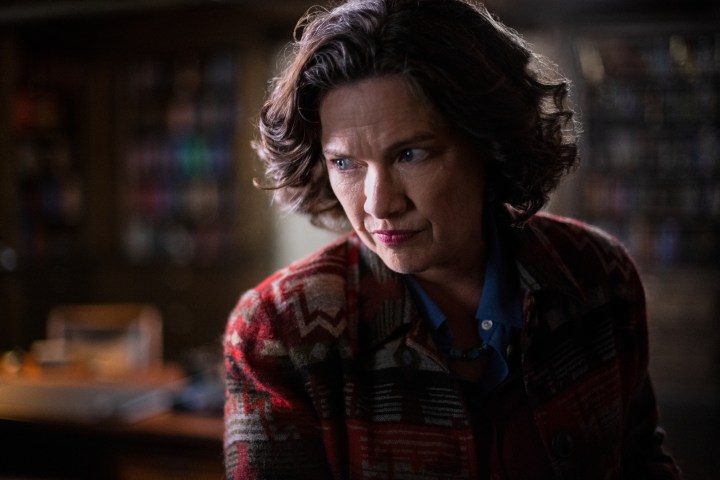

It’s ultimately A Nightmare on Elm Street star Heather Langenkamp who emerges as The Midnight Club’s secret weapon. Not only does Langenkamp bring a calm and mature presence to the YA series as Dr. Stanton, the head of Brightcliffe, but she also pops up as a different character in nearly every one of The Midnight Club’s short stories. In doing so, Langenkamp is able to both showcase her impressive versatility and frequently bring the kind of knowing, tongue-in-cheek energy to The Midnight Club that the series, frankly, could have benefited from having a little more of.

Unlike all of Flanagan’s previous Netflix shows, though, The Midnight Club’s season finale also opens the door for the series to return in the future with more episodes. On the one hand, that means The Midnight Club concludes with several of its storylines and central mysteries partially unresolved, which may come as a disappointment to those who are familiar with Flanagan’s previous limited series. On the other hand, a second season would also give The Midnight Club the chance to smooth out and address the problems of its first. Right now, the series is an enjoyably imperfect YA horror adventure that is only truly hurt by the fact that it has the potential to be much, much better.

The Midnight Club is streaming now on Netflix.