“A great song is a great song. And you know it when you hear it.”

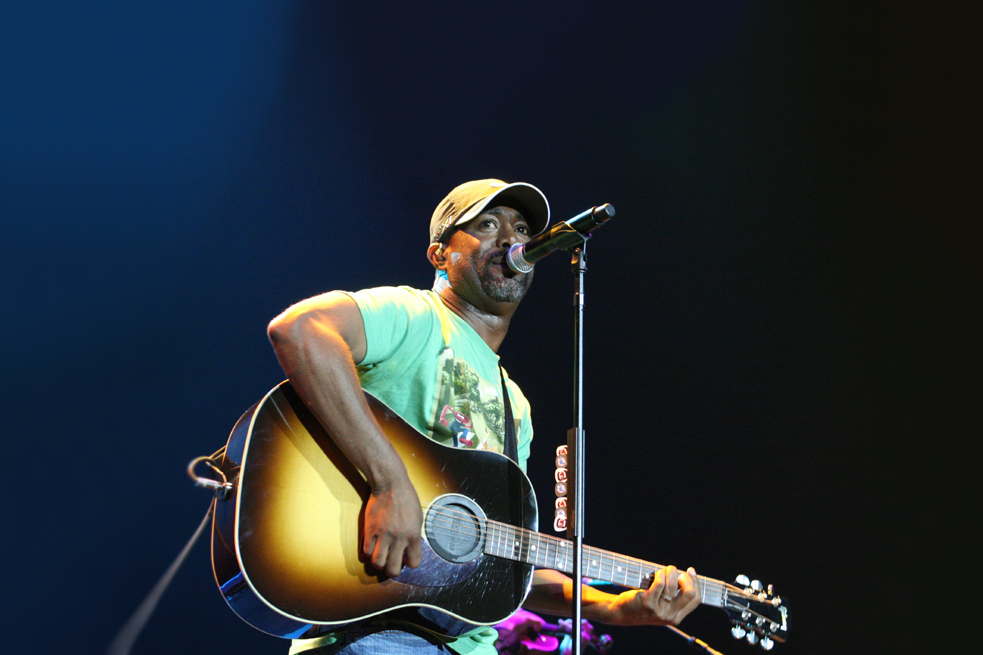

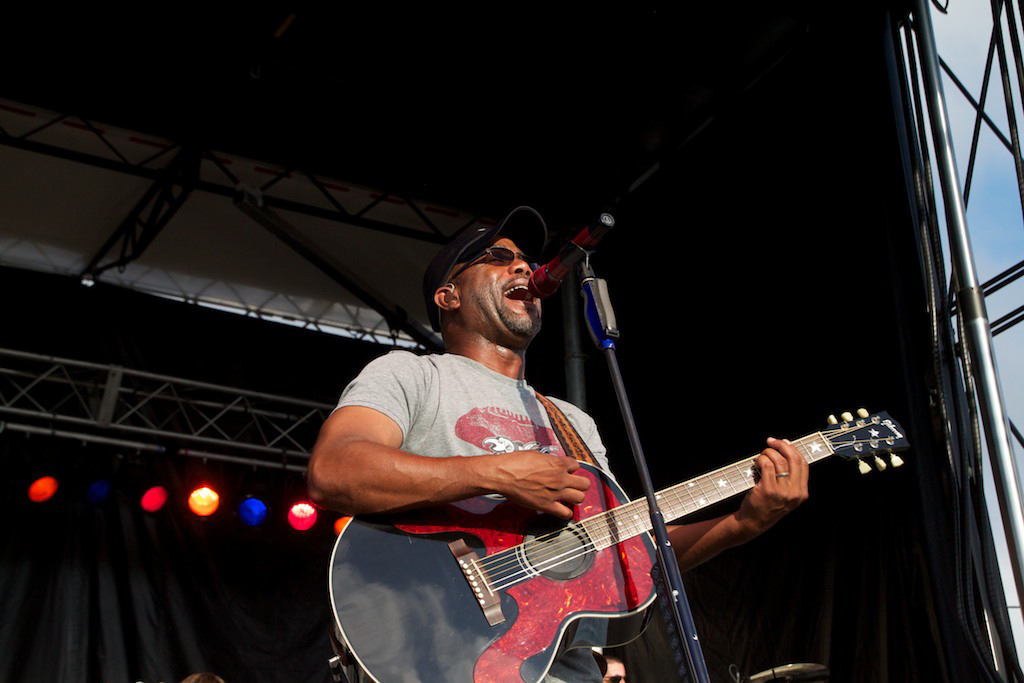

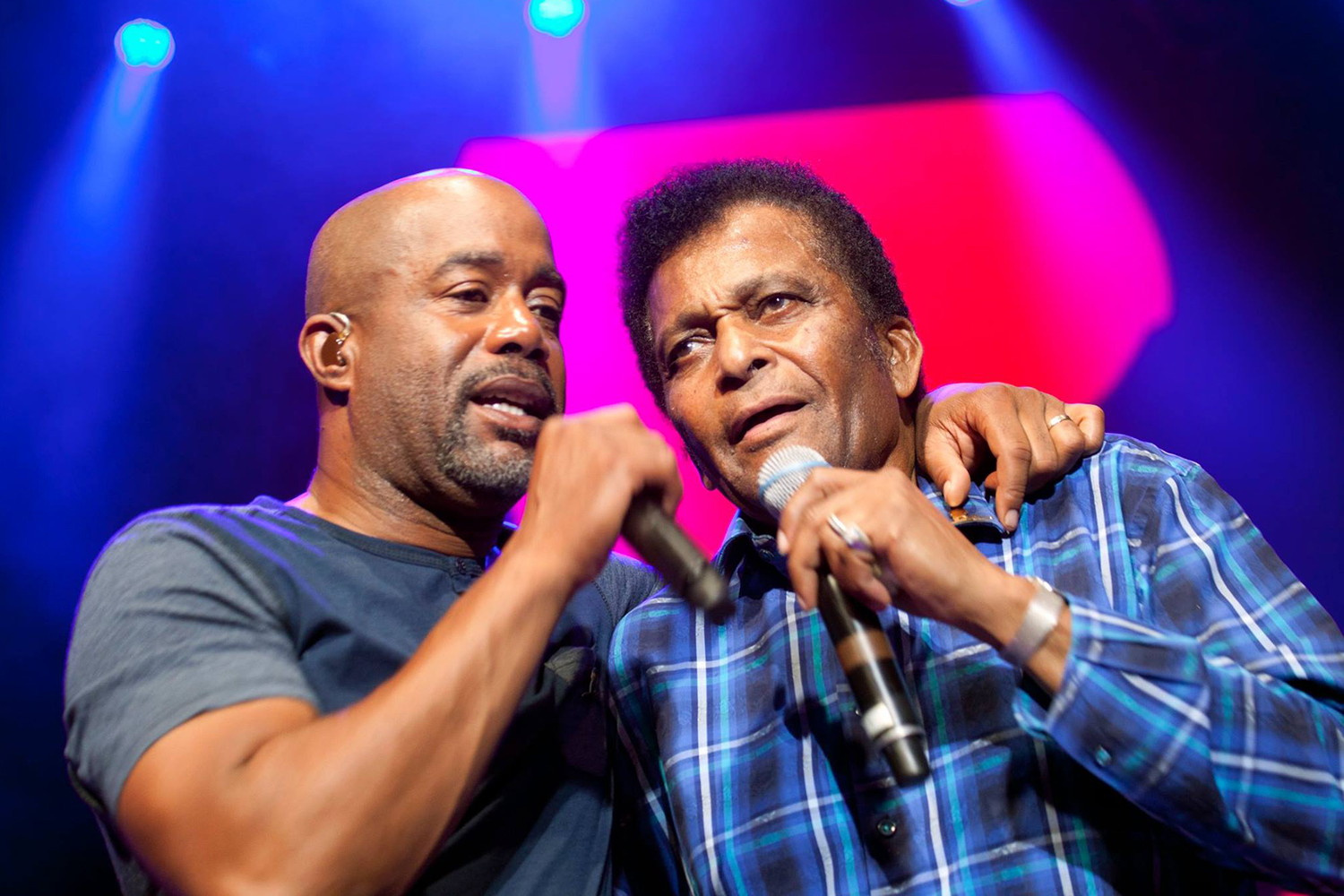

Is there a bigger crossover success story in country music than Darius Rucker? The onetime frontman for the megamillion-selling Hootie & the Blowfish has seven number-one country songs under his belt to date, and he’s just released If I Told You as a digital single via Capitol Records Nashville, which immediately became the most added song on country radio.

“The minute I first heard this song, I kind of teared up, because I thought, ‘That’s so me,’” Rucker told Digital Trends. “I said to my producer, Ross Copperman, ‘Were you guys in my head when you wrote this?’ [Copperman co-wrote the song with Shane McAnally and Jon Nite.] It’s such an honest song. And that’s so hard to say to people: If I’m with somebody and I tell them all the things that are wrong with me, all the bad things I’ve done and all the stupid things I’ve done, could you love me anyway?”

Rucker called Digital Trends during a tour break to discuss how he wants his vocals to sound on record, his feelings about streaming and vinyl, and why his brother thought he was “punishing” him by giving him a Jimi Hendrix album.

Digital Trends: I really like the arrangement on If I Told You, because it starts nice and subtle with the piano and drums before you come in and start singing. One of the lines that got me the most was the way you sang, “There’s no fixing me.” Do you have specific goals for how you want your voice recorded?

Darius Rucker: Yeah, I do. I really want the vocal to be real. It’s not going to be a live, one-take vocal, because it’s hard to do that. And I’m a real critic — I criticize myself a lot. A lot of times, I don’t want to listen to my stuff, because I’m thinking maybe I didn’t do my best. But there are moments in that vocal, like the line you said: “There’s no fixing me.” Every time I hear that, I go, “I couldn’t deliver that line any better than that.”

It’s an honest vocal, and I believed you meant every word you sang there. Sometimes, I’ll hear vocals Auto-Tuned or produced to the point where the character of the vocalist gets taken right out of it for the sake of precision, and I don’t like that. I like hearing you, and believing you as an artist.

That’s the one thing I want with my vocals, just as you said — it has to be so honest, and so real. I’m just really proud of that one.

What other songs of yours do you feel your vocal has been recorded exactly how you wanted it?

I think It Won’t Be Like This for Long [a number-on country single from 2008’s Learn to Live] was so real, just like Alright [another number one from Learn to Live] was. The ballads are the ones where I feel like that the most. I was listening to I Got Nothin’ [from 2010’s Charleston, SC 1966] on the radio the other day, and I thought, “Man, that one hurt,” you know? (laughs)

That’s what a good song is supposed to do to you as the listener. I know people like to categorize these songs as country, but it’s all American music to me.

That’s one of my pet peeves. People always want to put something into a category — this one or that one. You know, a great song is a great song. And you know it when you hear it.

That’s so true. When you and I started getting into music, we were vinyl guys. Is vinyl still a big thing for you? You’re putting your albums out on wax, which I like to see.

Oh yeah, we put out vinyl on every record I make. It’s coming back so much. I was shocked — I was in Barnes & Noble the other day, and all those great records I had with all those songs I loved as a kid were all there on vinyl. They’re selling them for $35 now, but… [both laugh]

Vinyl always sounded so different. A kid might not argue that it sounds better, but for me, it’s so much better to hear that pop and that needle going down on that music.

Do you still have a turntable?

Oh yes, because my daughter and my son are getting into vinyl now. They love it. The first vinyl they had was [the Eagles’ 1976 megaseller] Hotel California. And it’s kind of great to hear kids aged 12 and 8 sing every song on Hotel California.

That’s awesome. What was the first record you bought for yourself that still has impact on you?

I’m not mad at the industry, but I get .001 cent whenever somebody streams a song.

I guess the first ones I actually bought for myself that I really remember losing my mind over were Barry White’s Greatest Hits (1975) and Billy Joel’s 52nd Street (1978).

It’s interesting you say that, because 52nd Street was exactly the first album I bought with my own money as a kid for my birthday when it came out.

Really? Wow! For me, 52nd Street is quintessential Billy Joel. I bought that record as a kid and listened to it so much. Those are the first two that really blew my mind.

With both of those artists, I can see the parallel between you and really good singers and good songwriters, something that’s filtered over into what you’ve done in your career and the approach you’ve taken with your music.

That’s what it’s all been about for me, ever since I was a young kid. It wasn’t about R&B or country or rock and roll — it was about, “Do I like that song on the radio?”

Growing up in an all-black neighborhood, you try to listen to Buck Owens and Billy Joel and what you hear is, “Oh, you like that white-boy music.” I was lucky my mom always got my back.

I was going to say, you could have had some seriously tough times there.

They were. I remember my brother was always a jerk to me. One time he bought Jimi Hendrix’s Smash Hits, and he gave it to me because he didn’t like it, thinking it was a punishment. [both laugh heartily]

I’ll take that form of punishment!

Exactly! I was like, “Thank you!”

You’ve sung some Hendrix material before, right? I’d love to hear you do Little Wing.

Oh yeah, we covered a couple of Hendrix songs back in the early Hootie days, like Castles Made of Sand [from 1967’s Axis: Bold as Love].

I’m curious to get your thoughts about the streaming universe.

I’m not mad at the industry, because that became the way that it is. All of us musicians wish we got paid more because the pay for it is so small. You see the CEO of Spotify taking home something like $7 billion, or some crazy number (laughs), and I’m getting .001 cent every time somebody listens to a song. But, you know, it’s just the way of the world. It’s what happened, and it’s how it is.

I think it’s crazy. Without the music, you have nothing. That’s the thing that really gets to me. Right now, you’re all making so much money, and we aren’t making any. That’s crazy. You have to explain it to some people that music is not free.

The thing is, when we started in Hootie & the Blowfish and got big, the only reason you toured was to advertise your records, because you were making so much money selling records. And now, the only reason you make a record is to advertise your tour.

So having the new song out in time for your Good for a Good Time summer tour works.

Yeah, because it helps so much. You get the song on the radio, and they know you’re coming to town. And they like the song. We were already doing great before the song got added to radio, but now that it’s out, we’re selling more tickets. People hear it and they go, “I want to go see that song.” And that’s pretty cool.

Why do you think so many people gravitate to your live shows?

People who have been at the shows already know how much fun they had. You can have a good time and bring your family, your girlfriend, your best friend, or all of your friends and have a real wild party out there. That’s what people want to do. They want to go to shows and have a good time — and they want you to sound good.

To me, part of listening to an album was holding the album, and knowing everything that was in there.

I want you to come to my show and say you had so much fun that you want to come back and do this again next year. That’s what it’s all about now — finding that cool thing to do in the summer. Some people will go to five or six concerts just in the summer. And I want to be one of those people who can make that happen.

I bet there’s probably a whole generation of people who don’t even know who Hootie & the Blowfish are.

I was saying earlier in the day that I’ll play Hometown Honey, and these little kids will go crazy, and then I’ll play Let Her Cry, and they have no idea what it is.

Is that a strange thing to you? You have diamond sales for the album that song was originally on [Hootie & the Blowfish’s 1994 debut Cracked Rear View, which has sold over 16 million copies to date and is the 16th best-selling album of all time].

No, no; it’s just the way of the world. I’m glad that, 23 years into a career, I can get on a big stage and still have young people come out and hear me sing, even though they may not remember the songs that made me famous. They remember the songs I’m making now, and they want to hear them. That’s a pretty cool thing to have that wide a demographic of people coming out to see you play.

Do you feel people have a different relationship with physical forms of music than with 0s and 1s?

Oh absolutely, no doubt about it. We would be sitting there listening to a Talking Heads record and all these records that you would fold open and look at the inside and the inlays. You took out the sleeve and saw all the stuff on the inside. It was mind-blowing to sit there and read that stuff.

Even when the CD came along, it was still great to open up a CD case and take the booklet out and look at it and see who wrote the songs, and they’d have the lyrics in there. Now you just go on your phone and download it, and that’s it.

We did that for hours back in the day. When [U2’s] The Joshua Tree came out [in 1987], I spent hours sitting there just looking at that album and listening to the music over and over and over, going, “Man, this is just unbelievable.”

To me, part of listening to the album was holding the album, and knowing everything that was in there. That was a huge thing for me and a lot of people, and now it’s sort of all gone.

Did you ever think when Hootie & the Blowfish were playing all those frat parties back in the day that country would be such a big part of your life?

Yeah, I used to tell people back when Radney Foster’s Del Rio, TX 1959 came out [in 1992] that I was going to make a country record someday. I would say that all the time.

And, you know what — I got to do it. Country music is something people go out to Target and buy. That’s another reason I love being a part of it. I still make records with the mentality that we’re making an LP. That’s what I think about when I’m making music.