“I think we should be working in high-res all the time. I don’t even think there should be MP3.”

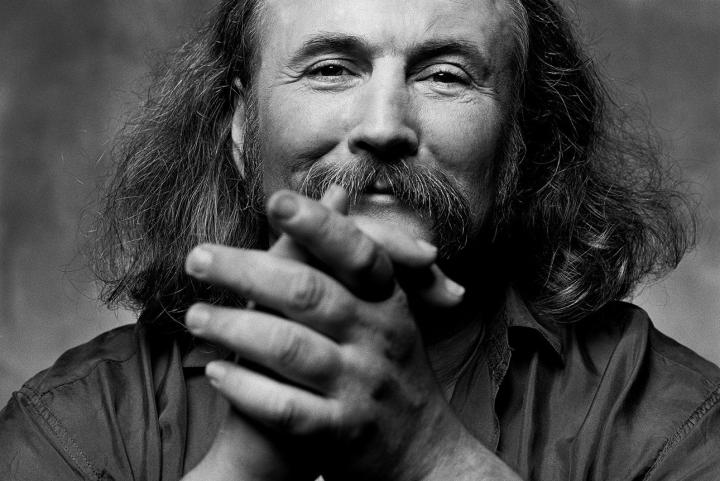

David Crosby has never been afraid to speak his mind and share his opinion of the state of the present, no matter what decade it is. For well over a half-century, the legendary singer/songwriter and lynchpin of Crosby, Stills & Nash (& sometimes Young) has been passionately forthright about his aversion to social injustice, political chicanery, and environmental chaos, and he’s just as staunch when it comes to loving high-resolution audio. In fact, Crosby insisted on high-res as the absolute standard for the 2014 release of his fourth career solo album, Croz, especially after hearing the 192-kHz/24-bit remasters Graham Nash produced for last summer’s ear-opening CSNY 1974 box set.

“It had to be available at nothing less than FLAC or lossless,” he said recently. “We made sure HDtracks had it at 192/24, and Pono will have it that way too when they’re ready for it. Croz deserves it. There’s stuff on there we really want you to hear.”

“All of us hate MP3s because they deliver only 15 percent, maybe, at best, of the music that we made.”

Digital Trends sat down with Crosby, 73, for a late lunch in midtown Manhattan to lament the ongoing failure of MP3, weigh the importance of overtones in recording, and underscore the talents of female singers. It’s been a long time coming.

Digital Trends: I’m glad to hear high-resolution audio is as important to you as it is to us. What is it about high-res that speaks to you?

David Crosby: Well, it’s just that all of us — and it’s not just Neil [Young]; Neil’s sort of a fanatic about it — but all of us hate MP3s because they deliver only 15 percent, maybe, at best, of the music that we made.

Right, because you essentially have 0s and 1s filling in the blanks of what you actually did and heard in the studio. And what you hear during the mastering stage often doesn’t come out that way on the other end either. As a listener, I often feel like I’m missing things you wanted us to hear.

Yeah. You’re being cheated. It’s very definitely a bad thing. We absolutely need to address it.

High-res makes such a huge difference, man. I can’t change the world, you know, but I really believe Neil is totally correct. We need to go to high-res because we go to a great deal of trouble to try and really get the information from the guitar, from the keyboard, and from the voice, so that the overtone structures are there — so that the magic is there.

Especially when it comes to music that’s harmony-driven — like a lot of yours is — it’s a shame to miss out on hearing the individual character of each voice in that vocal blend. We’re not getting the essence of what you, the artists, intended.

Mm-hmm! Right! Exactly! And if you get an acoustic guitar tuned really right by ear — not by machine — then there are harmonic structures, overtones. There are notes in the overtones that are not being played on the guitar. They’re created by the interaction of the other note.

The same thing is true of vocal stacks, if you do them well enough. If you listen to my first solo record, If I Could Only Remember My Name (1971), the reason I won an audiophile award with that one is that the things are in tune enough to where they generate the overtones, and you can hear them on the vinyl, plainly. [The Bowers & Wilkins Society of Sound cited Name as one of its five Best Headphone Albums Ever in 2010.]

“I think we should be working in high-res all the time. I don’t even think there should be MP3.”

And the surround-sound mix for the album gives us the full breadth of the recording, making us feel like we’re right in the middle of it.

Yep, yep — that was what we were trying for … I’m still very proud of that record.

As you should be. What else do you feel MP3 is lacking?

Overtone structures is the first thing. Second thing is, the MP3 format doesn’t handle transients very well. But I think the biggest loss is in texture and the overtone thing. When Neil started in on it, I hadn’t really thought about it, and I wasn’t really paying attention; I was kind of distracted at that point in my life. But now that I’ve really had time to consider what he’s been saying, I’ve really been listening to things and studying it in the studio. He’s right. You may think he’s crazy; I know some people do. But I think we should be working in high-res all the time. I don’t even think there should be MP3.

I’m right there with you on that. A good example why is Find a Heart, the very last track on Croz, where there’s that great interplay between the saxophone and the Fender Rhodes played by your son James [Raymond]. For about 45 seconds, we get all the nuances of the interplay and interaction there.

Well, you’re hearing two master musicians who have been friends for a very long time. [Steve Tavaglione], the guy who played the horn, is really brilliant. He’s first-call woodwinds in L.A., the way Leland [Sklar] is first call on the bass and Dean Parks is first call on guitar. And when Wynton [Marsalis] played on Holding on to Nothing — Wynton’s tone is probably the finest trumpet player tone since Miles [Davis]. Just incredible tone.

That track totally made me think of Miles, who cut one of your tunes back in the day, in fact.

Yes. Guinnevere. Isn’t that out there? It’s out there! [Davis cut Guinnevere on January 27, 1970; the 18-minute version was first released in 1979 on the outtakes compilation Circle in the Round, and it can also be found on The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions.]

He walked up to me in the Village Gate and said [affects froggy-whispery Miles voice], “You Crosby?” and I said, “Yes sir, I am.” He said, “I’m Miles.” I said, “Yeah, I know that.” (both laugh) And I’m completely verklempt. This guy is totally (pauses) — I mean, I listened to Sketches of Spain (1960) maybe 4,000 times, and I listened to Kind of Blue (1959) even more.

Have you ever heard the 192/24 for Kind of Blue? It’s amazingly good.

Oh, I’d love to hear a high-res copy of that. I’ll have to get it.

I also love what Mark Knopfler does on What’s Broken. He has that instantly recognizable guitar tone —

”[Steely Dan’s Donald Fagan] can be as weird as a pair of snake suspenders, but he’s always very nice to me.”

Yeah. You hear two notes, and you instantly say, “That’s Knopfler.” And I want to hear it, because he has texture, and touch.

He has such a special touch in the way he works those strings.

He’s a picker. You ever heard that song he did with James Taylor, Sailing to Philadelphia (2000)? Oh, man, what a record. Oh my God, oh my God. Crazy. So good, such a great record. I mean, [Dire Straits’] Money for Nothing (1985) might just be the greatest single anybody ever made (chuckles), but Sailing to Philadelphia knocked my socks off.

I told Mark he’s probably one of the best Americana songwriters who was never born here. He writes America, the characters, and the feel so well. [Knopfler was born in Glasgow, Scotland, and grew up in Blyth, Northumberland, England.]

Yeah. Before I heard Sailing to Philadelphia, I didn’t know all that stuff about Mason and Dixon. I had no idea. I mean, I knew there was a Mason-Dixon line, but I didn’t know who Mason and Dixon were. And then it turned into the line that delineated the North and the South, and that’s where Dixie came from. Calling the South Dixie is a derivative of Dixon.

At the same time, the conversation between those two voices, Mark and James — they’re so good, holy shit. Both of them are such great singers.

So you must also love the record Mark and Emmylou Harris did together, All the Roadrunning (2006).

Oh yeah. I love Emmylou, period. Just crazy-good. She’s one of my faves. My other faves are Alison Krauss and Bonnie Raitt, who I think are two of the greatest female singers, right up there with Aretha. Alison Krauss just electrifies me. I can’t believe anybody can sing that well. And Bonnie has such soul. There’s so much heart in her voice, man. And she’s a great guitar player — it’s effortless, and there’s not a whole lotta notes. She doesn’t feel the need to go, “yippity yippity.”

You have a broad musical base to draw from, having been exposed to so many styles of music when you were growing up. As an attentive listener, you absorbed a wide variety of sounds.

My parents played a lot of classical music in the house. You listen to Bach’s The Brandenberg Concertos enough times and it’ll change how your head works. And then, all of a sudden, you’re listening to Weather Report, and your head is being stretched in another direction. I just wish people who are trying to do singer/songwriter music now — in pop music, it doesn’t matter; that’s just like four chords — singer/songwriters need to listen. And when they do… I mean, Donald Fagen sure as hell does. That’s my favorite band, Steely Dan. They’re incredible.

I love Donald. He’s an interesting person to talk to. Sometimes challenging, though.

He can be as weird as a pair of snake suspenders, but he’s always very nice to me. He’s just brilliant. That’s some of my favorite music in the world. I’ve listened to Aja (1977) at least a thousand times.

Oh yeah. That interplay between saxophonist Wayne Shorter and drummer Steve Gadd, during the second half of the title song, where they just play off each other —

And the drum solo! Isn’t that crazy? (Crosby bangs the Aja drum solo out on the table while scatting along to each beat.)

Did you have to pay a lot to get davidcrosby.com?

No, I didn’t, but I’m not exactly sure how that went. I do know that on Twitter, @davidcrosby was taken and taken and taken, so I had to do something else. [On Twitter, he’s @thedavidcrosby.]

Related: For their last-ever album, Pink Floyd recorded on a boat

Finally, what album from your catalog would you like to hear done in high-res next?

I’d like to hear Déjà Vu (1970) that way. I think there’s some really pretty, really wonderful stuff on there. I would love to hear that record in 24-bit/192. I really would. I think we owe it to people, and I think we need to keep working at it — those of us who give a damn, the audiophiles. We need to keep pounding away at it, because… (pauses) a lot of people simply don’t know. If they’re listening to music on earbuds (shakes head) — I’m as anti-earbud as I am anti-MP3.

There’s a ton of us people who really love music. We really like to hear those overtone structures, and you can’t do that on earbuds. And MP3 does not deliver them.