“I make albums. I grew up listening to albums, and I will always make albums.”

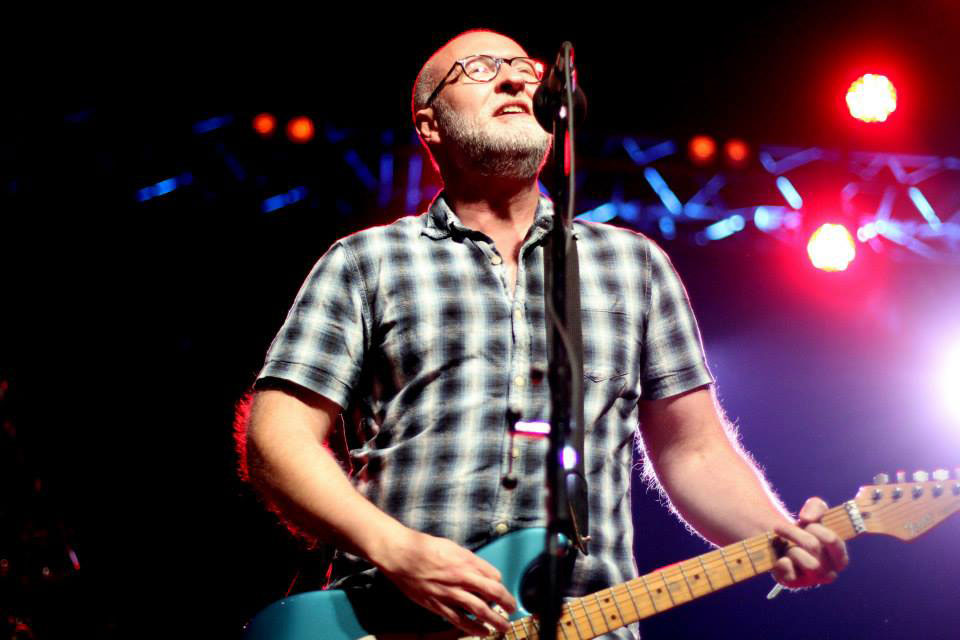

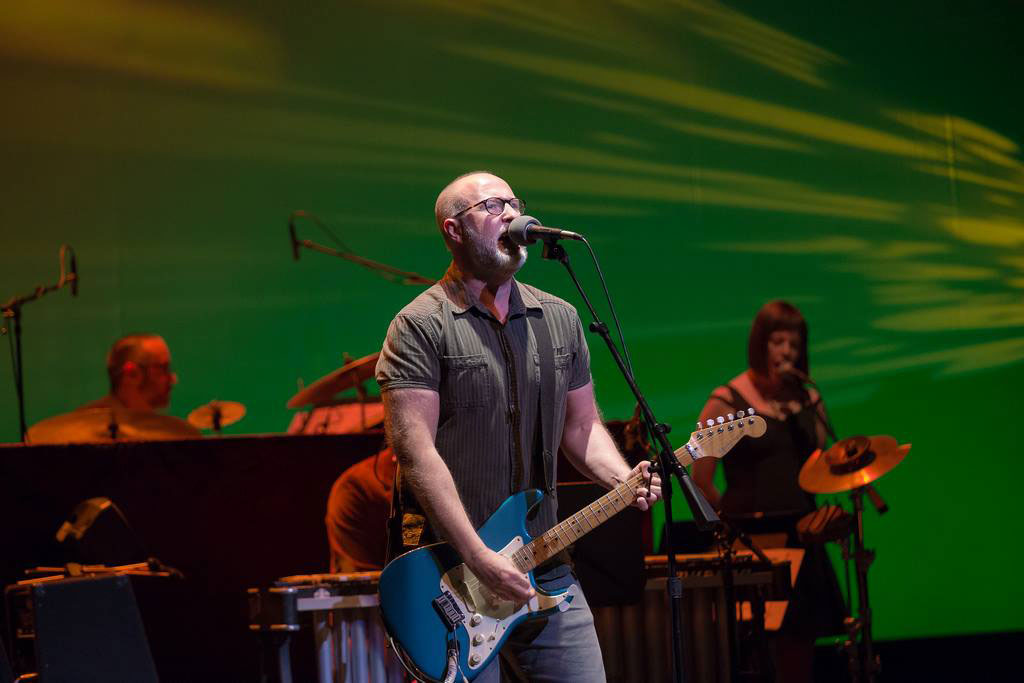

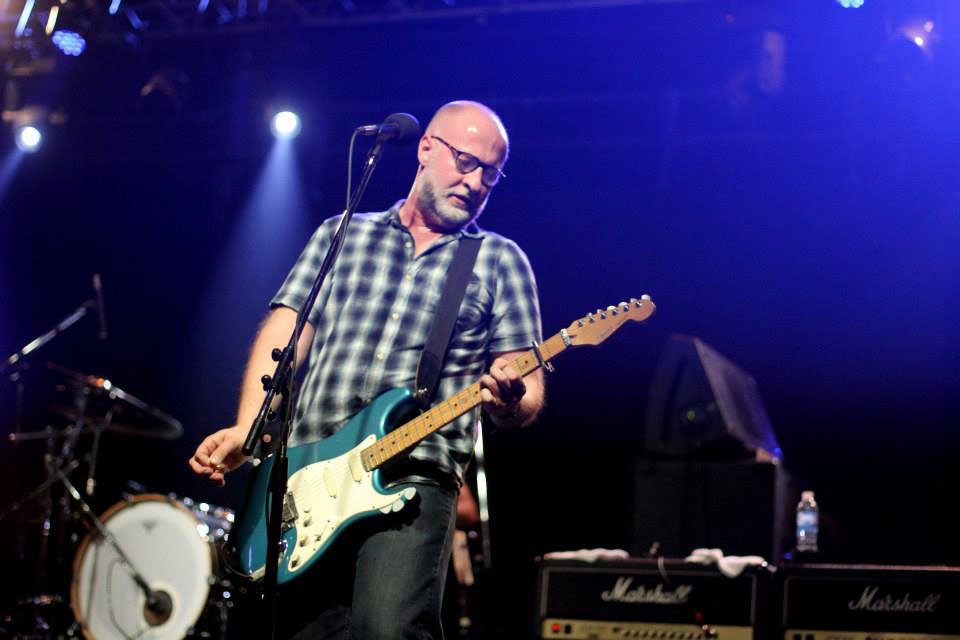

Car makers, take note: Post-punk pioneer Bob Mould can go from 0 to 60 faster than any vehicle that’s currently on the road.

Whether it’s via the ear-blistering caterwauler’s template of his St. Paul-based ’80s trio Hüsker Dü, the alt-rock swagger of his ’90s three-piece Sugar, or the blistering waves of Black Sheets of Rain that have defined much of his solo career, Mould’s intensity and passion gives a deeper meaning to the land-speed record concept.

And on his new solo album Patch the Sky, out today in various formats from Merge Records, Mould continues to do what he does best, darting from the screeching buildup of the perfect cure for insomnia known as Losing Sleep, to the muscular jam-driven wall of Black Confetti, to the escalating tower of riffology that is Monument.

“On the surface, the album is deceivingly simple, but some of the structural tricks are really cool,” Mould reports. “Like having an ever-slightly abbreviated bridge so a song gets to the chorus that much faster than it should. Or at the end of Pray for Rain, where you’re not going to hear that second chord substitution coming at you. You’ll be like, ‘Whoa, what song are we listening to now?’ That’s the one that opens the cash register. Ka-ching!”

Digital Trends recently sat down with Mould in a Brooklyn coffee shop to discuss the sonic trajectory of Sky, loving vinyl but not so much streaming, and helping birth the alt nation. There’s enough aural excitement on hand to make anyone Flip Your Wig.

Digital Trends: There are a lot of loud guitars on this record —

Bob Mould: There sure are!

And sometimes, your vocals are really forward in the mix, and sometimes they’re further back. How did you decide the vocal placement for each song?

Well, it depends. With Voices in My Head, right off the bat, it’s a statement of intent. So I want to get that clear up front and set the stage, with that first line being very clear — “If I decide to listen to the voices in my head” — then it’s like, “Oh, it’s an introspective record — literally.”

And then with song two, The End of Things, it’s like, “What is this guitar tone we haven’t heard before?” It’s a deep, lo-fi, simple rhythm thing. It’s a fun song with a lot of space so that when I play it live, I can move around a little bit. [chuckles]

I really like how you nailed the sound of Jon Wurster’s drum-cymbal interplay at the beginning of The End of Things.

Yeah — let’s get that cymbal sibilance out of the way so we can get to all the vocal sibilance that I’m so well known for! [laughs heartily]

“The only reason I listen to anything digitally on a computer or on a phone is just for portability.”

You know, it’s funny you have this one on top [points to the CD for Sugar’s 1994 release File Under Easy Listening], because this new album is the closest in sound to that one, just by not carving out all the low mids and having not as much compression at the end. We had the choice.

We did three rounds of mastering. The first one was natural, but needed help. The second one, we hit it too hard. It was the first time working with Bob Weston out at Chicago Mastering Service, and I had to learn how to be respectful of his craft, but also learn how to convey my specific needs without being… an overlord. [chuckles heartily]

Well, ultimately, it is your name that appears on the front of the record.

Yeah. But Weston does quality work, so there’s no need for me to go to him if I’m not going to use what he brings to it.

True. Overall, the album’s got the live feel that’s always been a hallmark of yours — everybody recording together.

Yeah, this has a lot of three-in-the-room rhythm tracks. We recorded at Electrical Audio in Chicago, [Steve] Albini’s place. The A Room is a very spacious wood and dark adobe brick room. We did a thing where we set up our backline just as we do onstage, and everything was miked up. When it came time to dig in, we had a whole other room for my cabinets, and a second drum kit and another bass rig set up in the isolation room, to get a real deep sound in that floating brick room that has the suspended floor. We’d learn in Room A as if we were rehearsing and then we’d move, but still be able to see each other.

Patch the Sky seems to me to be the right length for an album these days. And the songs work really well together as they flow along in sequence.

(nods) I make albums. I grew up listening to albums, and I will always make albums. The most important part of making an album is telling a story from start to finish, and this one is classic. I set that motif at the beginning. There’s a certain chord variation I keep referring back to in the record — that I-IV-minor-III that shows up in song after song. It’s setting all that stuff in front: Here’s the motif you’re going to see all the time. It’s an introverted record. Follow me as I go on this journey, as we go further into the water. It’s a work of art.

Ramones (1976) was the first album that really impacted you when you were growing up, right?

Ramones was the first one that made me realize anyone could do it. I mean, I bought [The Beatles’] Revolver (1966) when I was 6 years old. I grew up with albums that had 10 to 12 songs taking up 30 to 35 minutes.

Is vinyl still the preferred medium of listening for you?

It always has been, but vinyl has become more sacred to me over time. I have two different places in my house where I have vinyl setups. One is a music room where albums and other stuff live, and then in my workroom, I have my little late-’50s tube box 7-inch player, and I also have all my singles from the ’60s.

Nice. I have most of my dad’s old singles. He once asked me if I wanted his original Chuck Berry 45s on Chess and Elvis Presley 45s on Sun, and I was like, “Yes please!”

Mine were pulled off the jukeboxes. They’re a little worn.

They’re all well played, and well loved. One of my favorite 45s to this day is the cover Hüsker Dü did in 1984 of Eight Miles High [originally done by The Byrds, from 1966’s Fifth Dimension].

Yeah, it was the precursor to Zen Arcade (1984). As you know, that’s the warm-up song for how we set the levels so we could record Zen Arcade. [chuckles]

Eight Miles High always galvanized people whenever I put it on because it’s so loud and intense. Did you ever talk to David Crosby or any of the other Byrds about it?

They know of it. My memory’s a little foggy, but there was period in the late-’90s when Crosby, Stills and Nash were getting ready to do a record, and I was approached to maybe work with them. It might have been David. I really wish that had happened, but there’s still … time. [smiles]

What’s the optimal album length, in your view?

I think 40 minutes is the most you should try to accomplish at once.

The CD age kind of threw us off from good album-length editing.

What happened was it gave people that “I think we need to fill that up” thing. It brought down the overall quality of albums, which led people to sharing the one good song online, which then led us to Napster, and all of that. That was the beginning of the end of everything.

So you’re not a fan of streaming and the take-all-you-want digital download universe, then.

“Vinyl has become more sacred to me over time.”

I don’t use it, and I don’t think anybody should use it. It reminds me of tourists showing up at the all-you-can-eat buffet in Vegas. They stuff their faces until the vomit, and they get no nutritional value out of it — but they do it again the next day, because it’s cheap.

Why don’t you listen to your local radio stations that are promoting your local bands playing your local venue? It’s not that hard. And they have pledge drives every three months too. Put your money there.

If we do have to listen to things digitally, at least we have hi-res options like 96/24. Are you OK with that?

No, no. The only reason I listen to anything digitally on a computer or on a phone is just for portability. I don’t use it for critical use at all. When it comes to really listening to music, vinyl is what I listen to.

You spent a few years as a live DJ. What do you like about electronic music?

The loopiness of it. The drone, the progression, and the way they would introduce elements. Something builds up and then everything else disappears, and the transitions from every four to eight bars are cool. And the tones are just so crazy — they’re not organic at all. It’s like, “Whoa! I’ve never heard a kick drum sound like that in my life!”

Did you have a sense you were pioneering a certain sound in the ’80s? I remember sifting through the record bins to find whatever was cool that came out on the SST label, and Hüsker Dü were always at the forefront.

We were just… doing stuff. The thing about that music and that day and age was, it was happening everywhere. There were great bands in every town. But those great bands had nowhere to play in the late ’70s and early ’80s. So we had to build our own stages, so to speak, and then you invited your friends from out of town to play on the stage you built and vice-versa, and then it started to snowball. That’s how it all happened.

That’s the beauty of that era. Everybody had their favorite bands and their favorite labels. Some people loved SST, some loved Touch and Go, some loved Wax Trax!, some loved Dischord. All these labels had identities. You knew the sound; you knew what the artwork looked like.

I’m really grateful now to be working with Merge, one of the labels that has that kind of brand and identity. That’s what the ’80s were — more than any one band being greater than another. 120 Minutes started showcasing it, and then a handful of years later, the Teen Spirit video dropped [i.e., Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit, in September 1991] — and there you go. We won! [both laugh]

When you first heard Teen Spirit, did you feel like, “OK, we finally got to the next stage”?

When I saw the video, I knew it was going to work. In the summer of ’91, I did all of the shows with them and Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr. I was playing my 12-string. I was right there watching it happen, saying, “This might work.” And then when I saw the video: “It worked!” It brought the girls. And their boyfriends liked it too.