“I definitely feel high-resolution audio is the future.”

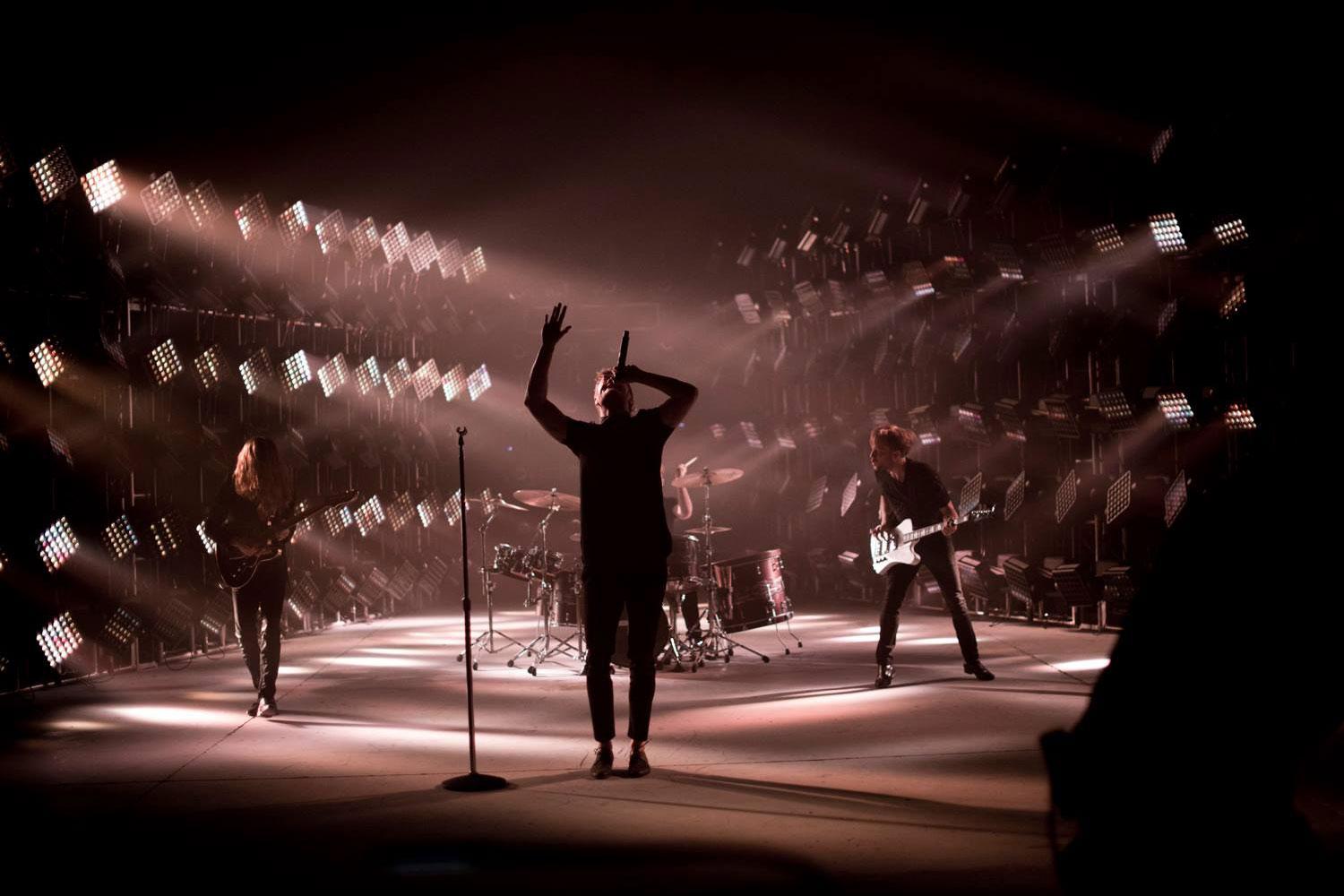

When it comes to modern rock, it doesn’t get any bigger than Imagine Dragons. The four-man Las Vegas-bred band’s multifaceted 2012 debut album Night Visions has sold more than 2 million copies and counting, and their ubiquitous hard-charging single Radioactive has moved over 9 million units, making it the best-selling rock song well, ever. (That’s enough to make your systems blow.)

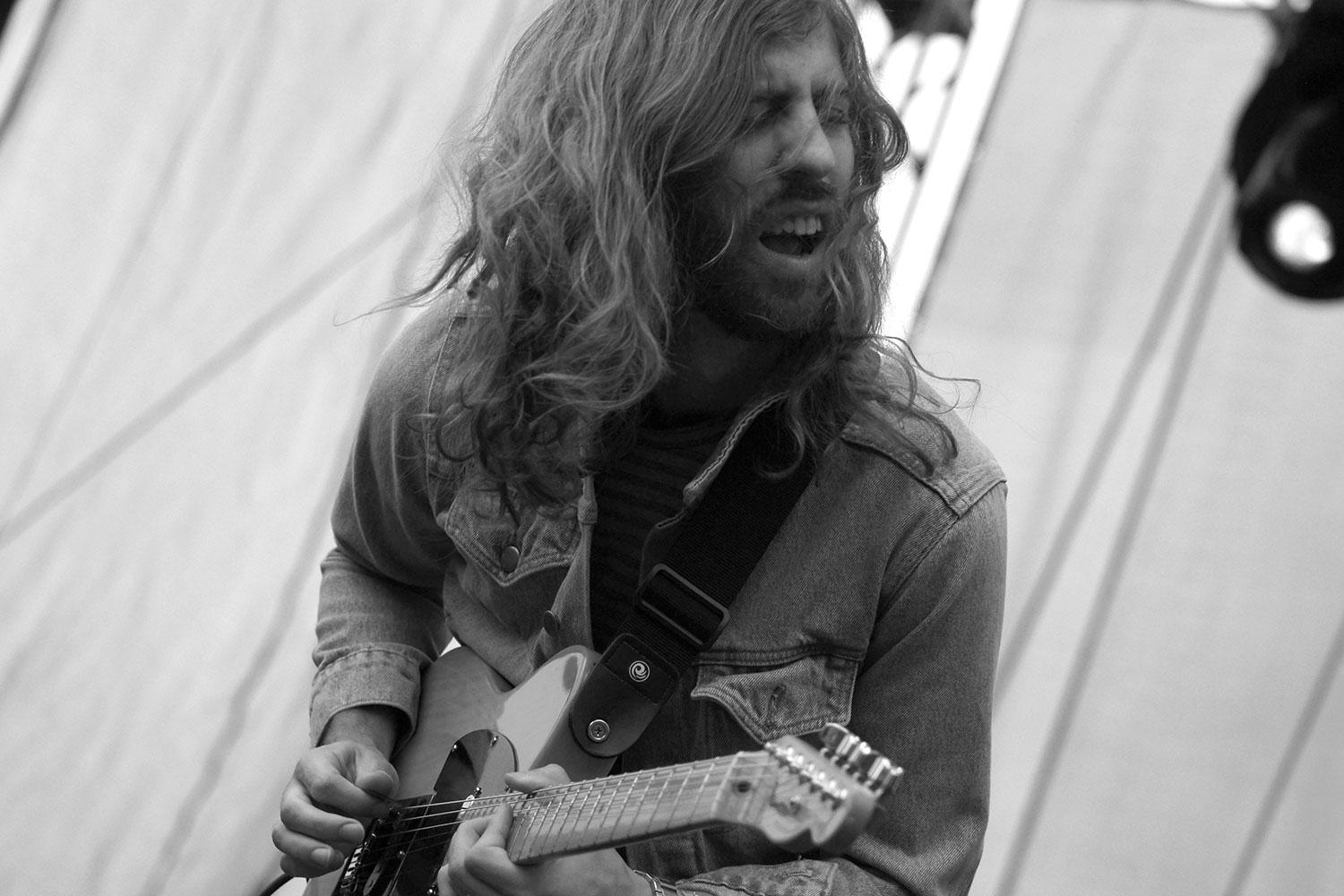

The secret sauce to this uber-successful Dragon attack is how the band deftly integrates its electronic sensibilities with alternative-rock instincts, dubstep, and vocalist Dan Reynolds’ instantly memorable melodies. Just try to stop yourself from singing along when he gets to the pivotal line “It’s where my demons hide” in the chorus to the 4-million-selling ballad Demons. And that’s not to mention how guitarist Wayne Sermon weaves his six-string, serve-the-song-first magic into the mix.

No one-trick popular pony, Imagine Dragons released Smoke + Mirrors on various platforms in February and saw it debut at number one. It’s not hard to see why. “We really wanted Smoke + Mirrors to feel like an old, warm record yet also be pop music that’s very current,” explains Sermon. Songs like the super-catchy stacked-vocal delay-driven rush of Shots, the seductive Middle Eastern dirge/James Bond spy theme mashup of Friction, and the off-kilter percussive sway of Summer all support the band’s S+M maxim. The album was produced hands-on by all four Dragons in the recently constructed Imagine Dragons Studios, which is credited throughout the liner notes via a cavalcade of mostly clever anagrams — Amigos in Danger, Gonad Migraines, and No Dream Is Aging among them.

As the band began prepping for its summer headlining tour, Digital Trends rang up Sermon at the, er, Ragged Minions Studios just outside Las Vegas to discuss how the band divvies up the production duties, how they try to maintain a song’s dynamic range, and what’s next for high-resolution streaming. Welcome to the new age.

Digital Trends: I don’t think you made the new album with smoke and mirrors at all. In fact, I think the production quality is even better than what I heard on Night Visions.

Wayne Sermon: Oh, thank you so much, we appreciate that. You know, it’s something we’ve actually been shooting for — to up our production game. We bought this old, weird ’70s house outside of Vegas and gutted it to turn it into our studio. It has a really strange layout, but it’s perfect for a studio.

We wanted the album to have some of the warmth of the vinyl we grew up listening to. As important as radio is to what we do — and we do love that part of the music industry — it’s really frustrating to hear this record on radio, just because it gets so smashed. Everyone is competing with everything else, but we have this very dynamic record that we put a lot of thought into, and radio just smashes the hell out of it. There’s not much left after that happens, just one level. There’s no loud, there’s no quiet. It’s just smashed.

That’s too bad, because this is an album that screams to be heard in high resolution.

Yes. It’s a very dynamic record, because the lows are very low and the highs are very high. Dynamically speaking, it needs to be played in a high-resolution form, which is the way I’d much prefer it be listened to — especially since we did it at 88.1kHz/24-bit.

“Everyone can play each other’s instruments, more or less.”

That’s what I like to hear. So what kind of gear did you have installed in the home studio — or house studio, I guess I should say?

Oh man, we went crazy! (laughs) We got a collection of all the gear we ever wanted. We got [BarefootSound’s] MicroMain 27 Gen2 monitors and the big ADAM SS-XV monitors. It didn’t make a lot of sense for our purposes to use a large console, so we got a Neve Designs 5060 centerpiece. It has the big channels and you can bust things out and it arcs really well, but we didn’t need a huge mixer because we weren’t going to be mixing the record here.

As far as outboard gear, we have a lot of API [preamps] and a lot of API compressors, like the 527 and the 525. Equalizers, we have some Neves — the Neve 1073 preamp/EQ, the Neve 2264 compressor, a Purple Audio compressor, a Shadow Hills mastering compressor, and True Systems preamps. What else? Neve Portico II master buss processors, a Universal Audio LA-610 MkII [classic microphone preamp/tube recording channel], some distressors, and some Earthworks pre’s, so, yeah. We got a lot of stuff.

It sounds like you got all the right tools for the job. And Hopeless Opus is probably among the most dynamic songs on the album, wouldn’t you say?

Yeah, that’s definitely one I spent the most time with dynamically, making sure it sounded right sonically. And I love our live room. Got to give a big shout out to a friend I went to Berklee with, who ended up doing the acoustics. He’s also a contractor, the one I called on to build the studio from scratch, and his name is Phil Liddiard. I said to him, “Build me a studio.” He really did an amazing job. He decoupled the walls, and added a floating room within a room. He hard-wired everything really well. It’s a professional-grade studio in a house.

Did you guys cut a lot of things live, looking at each other face to face in that live room?

Yeah, yeah, though probably more for the rhythm section stuff. Since we were producing the record ourselves, we found that one person at a time works better when the other members of the band are trying to produce. It’s really hard trying to be a musician and a producer at the same time. When I’m playing guitar, I want them all there for me, producing my guitar part.

I guess it’s like trying to direct yourself in a movie — it’s hard to step back.

It’s the same thing for us. It’s really nice to take it one person at a time and really think about what we’re doing and what we’re adding to the track.

Zeroing back in on Hopeless Opus, can you tell me your thought process for what’s going on there? You really don’t step to the front until about 3 minutes into it, when we get that pretty awesome solo of yours.

That’s sort of something that comes with time. When it was time to do the guitar part, there had been no guitar on the track yet, so I was like, “OK, time to put ‘me’ on.” I listened to the song and played a few different things that totally didn’t work (pauses) at all. So I went, “You know what? There doesn’t really need to be any guitar here at all,” and they went, “Oh yeah, maybe it doesn’t need guitar here.”

“Nothing sounds as good as old vinyl on a tube receiver with an amp.”

Then I was just messing around during the end with a fuzz pedal and these old Vox amps. And everybody went, “Wait! That’s awesome!” And I went, “No, it’s not! I was just joking around.” “Oh no, do a solo at the end!” I’m like, “Guys…” “No, do it!” So I was like, “Well, all right,” and that’s probably just the first take that’s on there.

That falls under being one of those happy accident kind of things that turns out to be the best thing for the song.

Exactly — and that wouldn’t have happened if I was in the studio doing my own thing. That’s something where being produced when everyone is around is really nice. That’s the way we did it with everyone. You can step away from being a producer when you’re just being a musician, and then you get all that input. It works really well.

Is there another example where you feel everyone’s input made for a better song?

Yeah, Smoke and Mirrors, the title track, is another thing really that was done in a positive way. I remember the big guitar solo at the end of that. It was a melody where I heard our drummer [Daniel Platzman] going [sings], “Nah nah nah-nah,” and I was like, “Oh, that’s a really cool melody to start with.” So I played that, and finished the phrase the way I thought it should be [sings the rest of it]. We share a lot of things like that.

There was a drum part I had the idea for, and there was a guitar solo that was really Platzman’s idea. We’re all good enough musicians that we can get around on one another’s instruments. I mean, I’m not nearly half the drummer Platzman is (laughs), but we each use the instruments to give the best input. Everyone can play each other’s instruments, more or less.

On that song, you do what I call a selfless solo. I clocked it — it’s about 3 minutes and 47 seconds into Smoke and Mirrors before the solo actually happens, and then it’s barely 30 seconds long. You could have said, “No, I want a bridge here where I can take a 2-minute solo.” But you didn’t need to do that, because it wouldn’t have served the song.

Right, and it’s taken us a long bit of time to finally understand that kind of stuff. I grew up being a shredder, and learned all of the Joe Satriani and Steve Vai solos —

Like we all do —

(laughs) Yeah, and there is a place for that. It’s what they do, and they do it so well. But a lot of people don’t want to hear that. They want to hear a good melody, and something that moves the song along. The guitar players I listened to growing up like George Harrison, Tom Scholz [of Boston], and Eric Clapton — it wasn’t about how fast they were playing, but what they were trying to get across to people and what they were saying.

Tom Scholz is a good example of somebody who knows how to move the song along and serve the melody first. And when you get to his solos, you feel like he’s earned that part of the song.

Absolutely! His solos are as melodic as the singer’s [Brad Delp’s] melodies. [Sings the melody line of Don’t Look Back.]

Is that your favorite Boston song?

“Maybe some simplicity is what this track needs.”

I think Don’t Look Back is my favorite, yeah. That’s so melodic. Nothing Tom Scholz did was super-fast. I can play his solos note for note. Like you said, he took command of that track, and that track was his. The tone of his guitar — I used to suffer trying to get that sound.

I don’t know if you know this, but if you invert the opening chords of More Than a Feeling, you get Smells Like Teen Spirit.

Are you serious? I didn’t know that!

It’s true! Give it a try later, you’ll see.

Wow, OK.

You mentioned vinyl earlier. Is vinyl still important to you?

I think so. I think it’s cool. Unfortunately, a lot of music on vinyl isn’t recorded analog, but some of it’s magical. I grew up listening to it. The first time I heard a Tom Scholz guitar solo was on vinyl with my dad, on an audiophile-grade tube receiver. I’d just sit there and listen to [The Beatles’] Abbey Road, Iron Butterfly, Boston, Badfinger; all kinds of stuff. That’s how I got into music and playing guitar — hearing it and listening to it on vinyl. To me, it has a special place in my heart.

It’s such a snobby thing for people to say, but it really is true — nothing sounds as good as old vinyl on a tube receiver with an amp. There’s something that’s just magical about that. Hearing a saxophone solo on vinyl — you can hear the breathing. You just can’t hear that anywhere else.

It is a special experience. You guys pressed 180-gram LPs for your two album releases.

Yeah, they’re big buggers. (laughs) Our manager came to us and said, “You could do it this way or that way,” and we said, “Let’s go all the way. People are buying vinyl, so let’s give them what they want.”

Tell me about to the intro to Shots — what did you use for the reverb there?

That was the Eventide H7600 [harmonizer], the reverbs we use for the guitar. Most of the delays on the record are done with the Eventide. I’m actually bringing that one on the road with me so that sound on the guitar will be replicated.

Good call! Was there a discussion about how many tracks you could put on each song?

For us, it’s like, “How much stuff can we put on without it being cluttered? How much is too much?” It’s like, when a painting is done, it’s done. You let the paint dry, you know? There’s definitely such a thing as adding too much stuff. You can be too heavy-handed with it, and that’s something we’re still learning as producers — when to lay back, when to add more stuff, when to say, “Maybe some simplicity is what this track needs.”

You guys wrote a lot of the album on tour, and you even did it super-rough sometimes, on USBs.

“It’s pretty nice in this day and age that you can get your ideas together so quickly.”

Most of the songs on the record started out as rough demos. The beginning of Shots started from me sending Dan a riff [sings it] — just sending him that simple riff in the middle of the night. He got that part and made it into something different, into a different arrangement. That’s how a lot of these songs started. Late at night, he’d ask me if I had any really heavy licks, and I’d go back to my hotel room and write a bunch of guitar licks. He’d pick some, put them together, and sing over them. That’s how a bunch of these songs started. It’s pretty nice in this day and age that you can get your ideas together so quickly.

Since Tidal has been in the news of late, do you have any thoughts about streaming services and high-res audio?

I heard about the Tidal thing and how they’ve gotten some blowback from fans. I don’t know enough about it yet to draw a conclusion, but I hope they can find a way to pay artists more money. To me, it seems like another streaming service and not a social revolution, but I do hope we can get more music at higher resolution.

The sticking point for a lot of people is, “Do I want to pay $20 a month for hi-res files?” Audiophile geeks like me will, but what about everybody else? Will they pay for it and really “get” it?

Exactly. That’s always been the tricky thing with audio, hasn’t it? You get different people saying how this new thing is better than another format, and then maybe they start paying attention more when they’re listening: “OK, how does this actually sound?” I really feel if people just sit and listen to a full, 88.1/24-bit track, they’ll immediately get the difference. It’s really there.

On any kind of service that has a simple player or you’re just listening with crap earbuds, things like the hi-hats just sound awful. Part of it is on us to make songs with better quality without the listener sacrificing the way they want to hear it. It’s on artists and consumers to work together to find something that works.

You guys have done a great job giving us a template for finding that with Smoke + Mirrors, because it’s a great-sounding record. You have to pay attention to what’s there to appreciate all the layers.

You have to spend time with it, yes. It’s something people should do other than listen while they’re cooking or driving in the car. Like I said, it’s up to us to do our part to do what we can and further that, whether it’s Tidal or something else. But I definitely feel high-resolution audio is the future. And we definitely want to be a part of that universe, wherever it is.