“The hardest thing to do is to create your own style.”

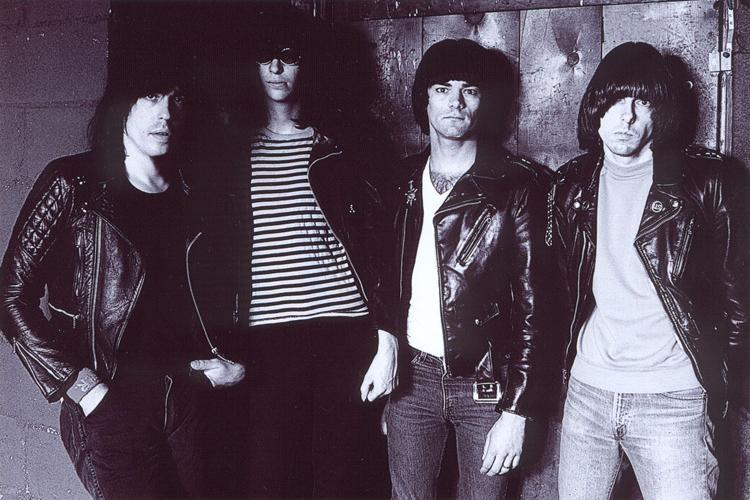

If there’s one band that can lay claim to fashioning a music genre, it would have to be the Ramones. Fusing the pure adrenaline rush of rock, garage, and metal to create the sound that we call punk rock, four scruffy lads in leather jackets and ripped jeans from Queens, New York blew the lid off of the rock establishment when they dropped their lightning-fast 29-minute self-titled debut album on Sire Records in 1976. Popular music hasn’t been the same since. “I think more people wanted to sound like the Ramones than The Velvet Underground,” believes Marky Ramone, the band’s longest tenured drummer. “So many bands try to imitate us. Anywhere I go in the world, I hear it.”

When the band’s founding drummer Tommy Ramone wanted to move out from behind the kit and into the production booth fulltime, the Ramones wasted no time in scooping up Marc Bell, who’d pounded the skins for seminal early ’70s bands Dust, Wayne County and the Backstreet Boys, and Richard Hell & The Voidoids. Quickly rechristened Marky Ramone, he laid down the beats for 1978’s Road to Ruin, which features some of the band’s most indelible songs, including I Wanna Be Sedated and I Just Want to Have Something to Do.

“You know what I don’t like about iTunes? It just sounds so small.”

All the good, the bad, and the ugly details about Marky Ramone’s wonderful punk-rock life are on display in his pull-no-punches autobiography, Punk Rock Blitzkrieg: My Life as a Ramone, out now in hardback from Touchstone, a Simon & Schuster imprint. Ramone, 62, recently sat down with Digital Trends in Simon & Schuster’s midtown Manhattan offices to discuss how (yes) jazz fits into the punk aesthetic, which songs he felt the Ramones covered the best — along with his wish list of the ones he wished they’d have done — and his assessment of the band’s enduring legacy. Hey ho, let’s go!

Digital Trends: How do you personally listen to music these days? Do you like high-resolution audio?

Marky Ramone: I do. I like CDs, but I also like getting downloads in WAV form. Why? Depends on the situation and what I’m listening through. It’s convenient, and I can’t walk around listening to vinyl. (both laugh) When I fly, I can just put on my headphones and listen to everything I download onto my phone. And I own everything I download.

You know what I don’t like about iTunes? It just sounds so small. You’re missing the details. It used to be about the soul, but now everything’s about convenience. But high-resolution audio — I love it. It’s great.

I’m glad to hear that. Some people think punk bands consist mainly of unschooled players who don’t know what they’re doing, but that’s not the case with you at all. Part of the secret sauce of your own playing style in the Ramones is that you studied drummers who were influenced by jazz, like Mitch Mitchell and Ginger Baker — not to mention some of the jazz greats themselves.

Yeah, like the guy from Dave Brubeck, Joe Morello. I listened to all those jazz greats, you know? I listened to Buddy Rich a lot, and also to guys like Clive Bunker, the original drummer from Jethro Tull. All these guys had a jazz influence, and they didn’t want to be called rock drummers. They’d get offended. It’s funny.

Ginger Baker sure got offended.

Oh yeah, yeah. I did a thing for the Ginger Baker documentary [2012’s Beware of Mr. Baker]. In one part of it, he goes, “I’m a jazz drummer; I’m not a rock drummer.” Even Charlie — Charlie Watts [of The Rolling Stones]. I was with Charlie a couple of months ago: “I don’t like rock. I like jazz!” It seems condescending to them. They had to come down a notch to do rock and roll.

Someone counting off “1, 2, 3, 4” — it’s not as simple as it sounds to play off of that.

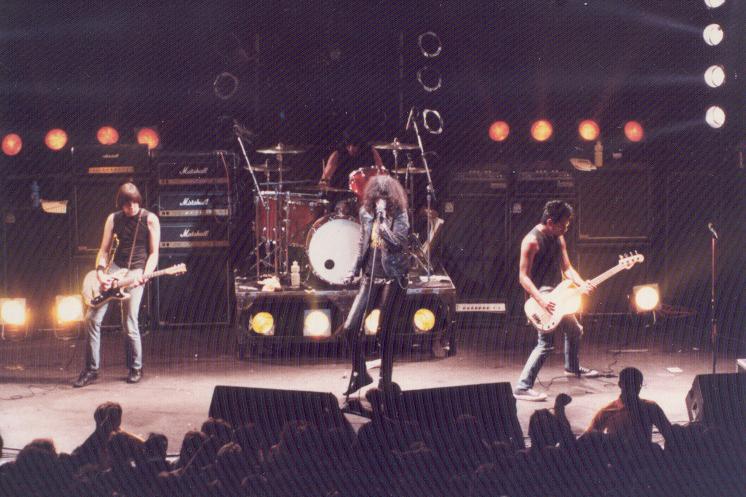

It’s not easy. Ramones playing isn’t easy. And you have to set the pace. Dee Dee [Ramone, the band’s bassist] was very erratic. When he counted “1, 2, 3, 4,” it didn’t mean you were gonna play that fast. You had to maintain a certain speed that you thought fit the song properly. We played a little faster than album speed, though. That’s a live thing.

And as you said in the book, when you sat down in 1978 to work on I Wanna Be Sedated, that’s where you found your pocket and your place in the band.

When I recorded Sedated, I wanted to play it heavy, and get a heavier sound than Tommy. I threw in a little fill at the end of the break going into the chorus — just as a lead into it, which wasn’t on the demo. I felt something was missing. I wanted to add a little tag there at the end of the guitar break. And it worked.

What was the reaction in the room? How did the other guys feel about that?

Oh, they liked it — and they were amazed I did it with one hand! They felt that it spiced things up. Because when I heard the demos, that was the best they could play it — the best Tommy could play it.

But in the end, that one note could be more effective than 100 notes. Like the guitar break in Sedated — it’s only one note. That’s all it is. I’d rather hear that than a six-minute guitar solo from some heavy metal band. I mean, I’m sure they’re all great, but to me, they all sound the same.

The hardest thing to do is to create your own style. And I don’t think styles are “created” — they just come to you. They just develop into what you are. It seeps into it. When you start thinking, “I want to have my own style,” it’s not happening. It’s gotta come through experience.

And like I said, I wanted to make it heavier, because of the time and because of the bands that were out there that we were up against; our competitors. You had The Clash, Van Halen — all these bands that were playing heavier. That’s why, on Road to Ruin, I wanted to do more floor-tom stuff. I tuned my snare drum a lot tighter than Tommy did. A lot of the time, Tommy’s snare sounded light and papery — which was his style. It was his choice. But I felt it needed more of a kick.

And “kick” is just the right word for it. If the snare sound isn’t there, it takes me right out of it.

(nods) And that’s why I cannot stand Subterranean Jungle (1983). At that time, the producer, Ritchie Cordell, was trying to imitate a drum machine. That ’80s, dry, let’s-put-the-towel-over-the-snare drum sound. It didn’t work. Not for the Ramones.

“When you start thinking, ‘I want to have my own style,’ it’s not happening.”

And I’m sitting there, listening to this happen. I’m the drummer of the band, and this guy is using this horrible sound to make it sound futuristic, or “at the moment” — you know, “follow the recipe.” It didn’t work. I had a big argument with him. He gated the cymbals too. Listen to the crash cymbals — they’re not even there! I said to him, “What are you trying to do to me? Listen to Road to Ruin. Listen to a great Ramones album.”

That’s one of the reasons I didn’t want to cover Time Has Come Today [by The Chambers Brothers] on that album. It was a horrible rendition of the song. I mean, we did great covers: Needles and Pins [The Searchers], Do You Wanna Dance [The Beach Boys], Let’s Dance [Chris Montez]. But Time Has Come Today? Come on, gimme a break. You can even tell Joey’s vocals were forced. It didn’t flow or come out naturally.

But some of the covers we did later on Acid Eaters (1994) is really good stuff. I chose seven of the songs on that album.

Which Acid Eaters covers do you feel came out the best?

My favorites are 7 and 7 Is [Love], because it’s very hard to play, Have You Ever Seen the Rain [Creedence Clearwater Revival], Can’t Seem to Make You Mine [The Seeds], and When I Was Young [The Animals].

Were there any covers left on the table? Did you have a big list?

Yep. What I would have liked to get on there was Kicks by Paul Revere and The Raiders. But the thing is, it was voted down because it had too much of a message. It was a “message” song. What else? Talk Talk by The Music Machine. But they couldn’t do that because it was too technical — too many stops, too many gos. After a while, if you become too much of a technician, you lose sight of the feel. And [Strawberry Alarm Clock’s] Incense and Peppermints. If those songs were included, it would have been outrageous.

Oh, man. You’ve just described what would constitute one of my favorite mini sets on the Underground Garage channel on SiriusXM. Incense and Peppermints is one of my all-time favorite songs.

Oh yeah. It is a great song. And that guy [Greg Munford] was only 16 years old when he sang it. What a great song. And it had a really good fuzztone break for the time — 1967.

Well, those were the songs I submitted. Oh, and there was one more — Touch Me. But we had already done a Doors song on [1992’s] Mondo Bizarro [Take It as It Comes]. I didn’t think they could do it properly, but I could do it. They coulda had Daniel Rey [who played on and produced three Ramones albums] play the bass and the guitar on that, you know what I mean? It’s really just a Bo Diddley beat.

Early on in the book, you were talking about how your band Dust would set up in a basement to record, and you’d play around with the microphone placements to figure out how you wanted the recordings to sound.

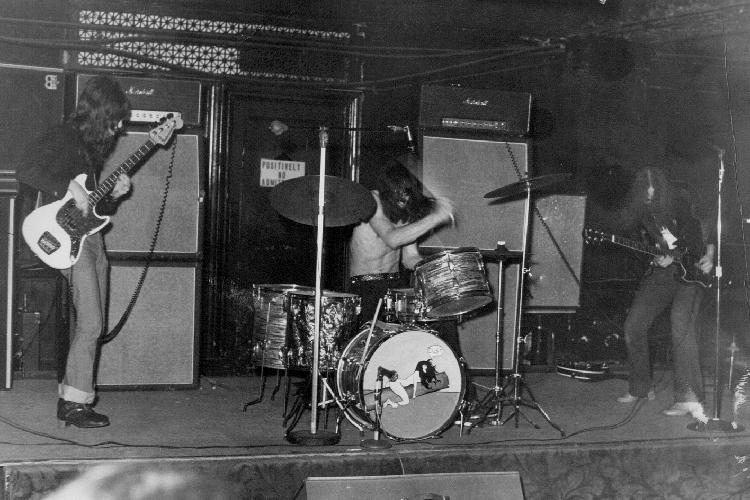

Well, the thing was, this was 1970. There weren’t that many American producers who knew how to work with a heavy-metal band at the time. The music was a lot louder than what they were used to. The guy we had always wanted us to “turn down, turn down, turn down,” and on the first album, I thought the drums were very low in the mix. The second album [Hard Attack], which we recorded in ’71 and came out in ’72, was a lot better because we knew at that point we had to have a lot more say in the mix — about the sounds, the tones, and where the microphones were located. And it worked.

What type of microphone placement do you insist upon now?

When the engineers put the mics on the kit, I’ll play something, then go listen back to it in the control room. If I don’t like what I hear, I’ll move the mics, then come back in and listen again. If it’s better than the engineer’s, we’ll use that. If not, we’ll keep doing it until I’m happy with the sound.

One more thing about Subterranean Jungle. There was a clause I put in the contract that no producer can tamper with my drum sound — that I have to agree, and that’s the way it has to be. And that’s it. But with Phil Spector, when we did End of the Century (1980) — he’s Phil Spector. I wasn’t gonna argue with him. I let him do what he had to do. It was a pretty wild experience, working with him for those six weeks. He never worked with a band like the Ramones. But I suggested some things to him. Some things were OK, and some things were hidden — which I can understand, with all of the overdubs, the guitars, and the Wall of Sound. What he’d usually do with a drummer is take their cymbals away.

Yeah, he even did that with Hal Blaine during those original Wall of Sound sessions.

I know — he took the cymbals away! So what would he use to enhance the treble? Tambourines. Maracas. Jingle bells. Things like that in the place of the cymbals.

Was that because Phil was concerned about things bleeding into the other tracks?

He didn’t mind things bleeding into other things, because that’s what made more of the Wall. But say if we had to stop sudden, and there was a cymbal wash over three-quarters of the song — you couldn’t go back to that point and re-record because of that cymbal wash. It was because of these techniques that he had only two of the four tracks to work with.

“We were four unique, sick individuals.” “In the end, it’s the music that matters.”

What are your favorite songs on End of the Century?

Ones that I like? I like Danny Says. I also like Do You Remember Rock ’n’ Roll Radio?, definitely. You’d say to DJs, “Can you play this?” Of course not, after they hear it: “This is against what I do.” I knew that one wasn’t going to be a hit because it was anti-disc jockey. So obviously the choice [for a single] was Baby, I Love You, a Ronettes cover, which Phil was very happy for. It made the Top 10 in the UK.

What are your favorite records that Phil produced?

Baby, I Love You, You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling [by The Righteous Brothers], and Be My Baby, by the Ronettes — one of the greatest songs ever.

End of the Century was an experiment and the punk purists didn’t like it, but it sold more than any single album of ours in a quick span. Just recently, the first album went Gold [certifying 500,000 copies sold] after 38 years. I wouldn’t yell that from the rooftops. To me, it’s a little embarrassing. I think it should have been Gold the first year.

The greatest hits album [Ramones Mania, 1988] went Gold, and the DVD I did, Ramones: Raw (2004), went Gold. But it’s surprising that Rocket to Russia (1977), Road to Ruin, and End of the Century didn’t, but they’re coming close.

And now we get to hear the Ramones on classic-rock radio every day. Did you ever think that would happen?

I was just hoping we’d get played on the radio anywhere, anytime, no matter what. So I’m grateful for that, yeah.

In the book, you say the Ramones are more the “rock” half of the phrase, “punk rock.”

Right. More rock. Our style was created, and it’s Ramones music, which so many bands try to imitate. Anywhere I go in the world, I hear it.

Is that where these bands go wrong, because they’re trying to imitate you instead of being original?

We were four unique, sick individuals. So you have to be in that category to create something like that, you know what I’m saying? Of course they’re not going to be as good as the Ramones, but it’s great that these bands are so into us. It’s an honor to be appreciated that much. It takes time and effort to rehearse, and money to record. There are bands making whole Ramones albums over. That shows it. There’s a whole new generation finding us.

And then you have bands like U2 writing a song about Joey [The Miracle (of Joey Ramone), the lead track on 2014’s Songs of Innocence]. You have Motorhead writing a song called R.A.M.O.N.E.S. [on their 1991 album, 1916]. You have KISS doing Do You Remember Rock ’n’ Roll Radio? [on the 2003 Ramones tribute album We’re a Happy Family]. It’s still as important than ever today, that song — and radio is worse now than when the song was written. So, better late than never.

The phrase “very Ramones” comes up a lot in the book. What would you consider to be among the most “very Ramones” things that happened over the band’s lifespan?

I guess trying to act our parts out in Rock ’n’ Roll High School (1979). That was one. Being on The Simpsons was an eventuality [in the fifth season’s “Rosebud” episode, which first aired on October 21, 1993]. Let’s see. Me and Joey on The Joe Franklin Show [in 1988] was very … surreal.

But the most “Ramones” moment would be getting into the van, and driving everywhere. Other things that stand out would be the US Festival [in 1983], the last show we did in 1996, and touring different countries. Doing the Stephen King song for Pet Semetary [in 1989] — that was really cool. There were so many things. We didn’t necessarily get along. We all had our disagreements. But we were a family, and a band.

What’s your definitive statement on the audio legacy of the Ramones?

In the end, it’s the music that matters. The images, the arguments, the petty animosities — people forget that there are a lot of good Ramones songs out there. And they just want to hear that song.