“When the drums came in, everybody said, “F***ING HELL! What the f**k is that?” Nobody had ever heard anything like that.”

You can feel it coming, right around the three-minute mark. The song has been building to an inevitability, courtesy of the track bed set by a Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 analog synthesizer, a Roland CR-78 Disco-2 drum machine, and some ominous, processed electric guitar riffs. A somber, Vocoder’ed vocalist intones, “The hurt doesn’t show, but pain still grows — it’s no stranger to you and me.”

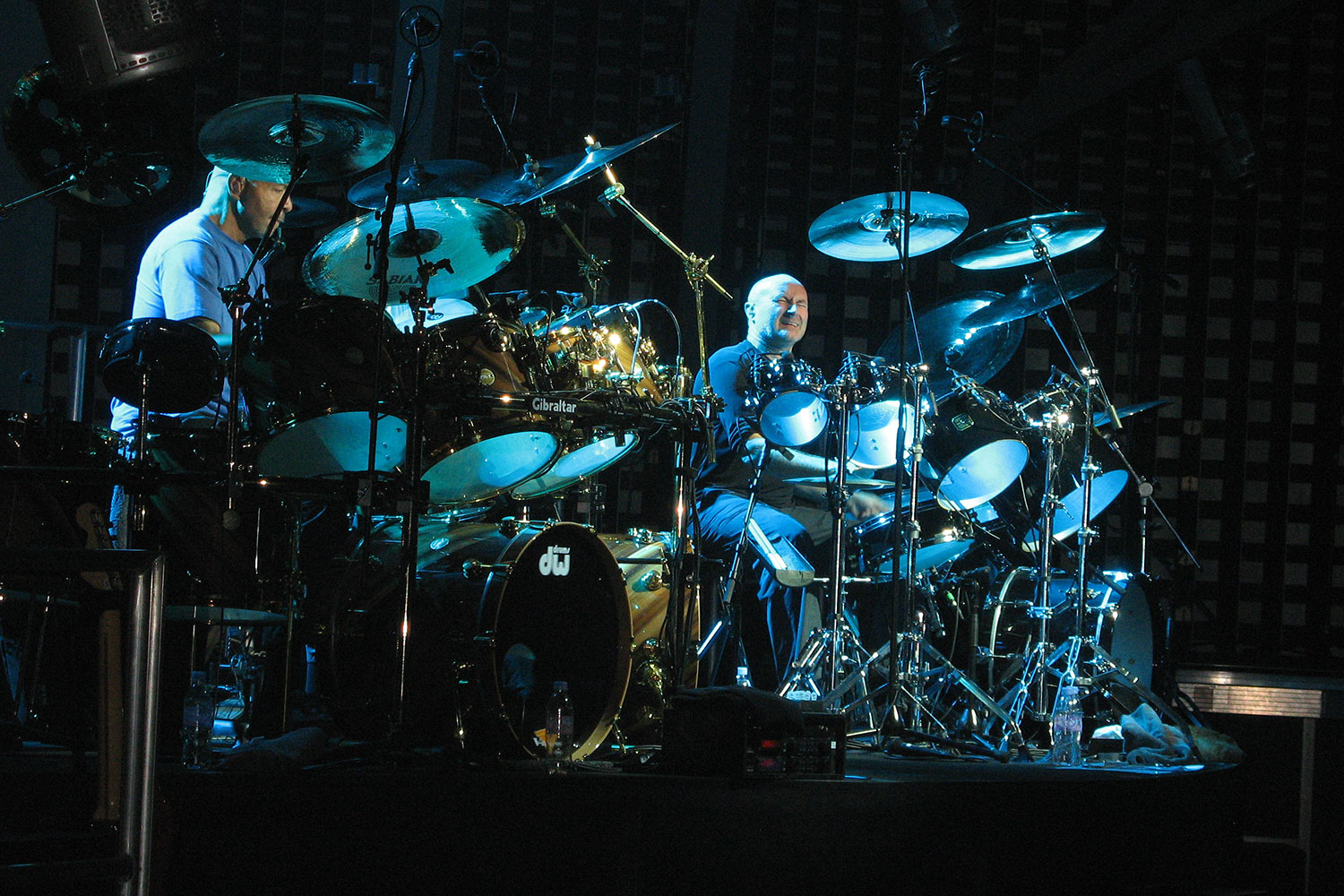

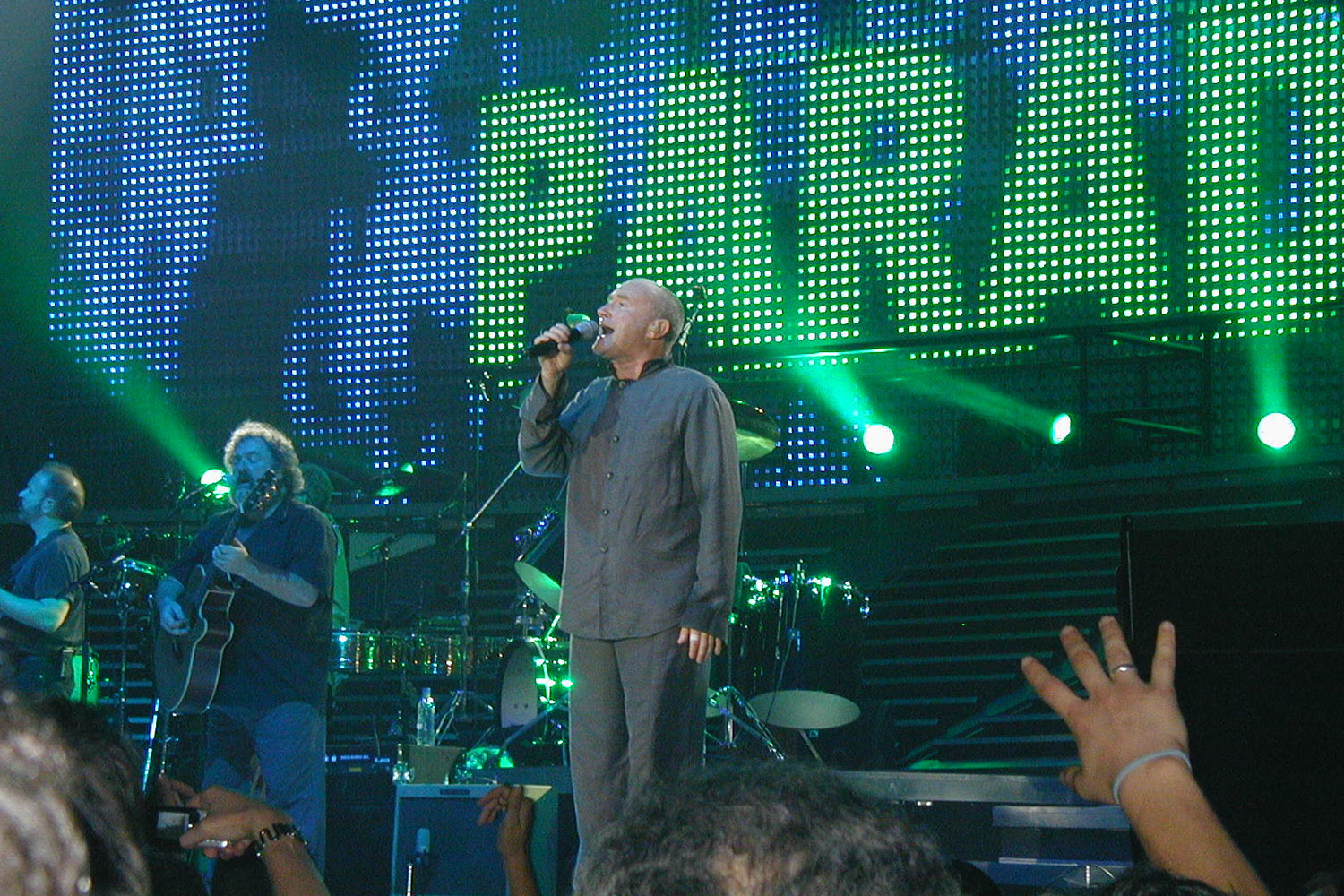

And then Phil Collins lays into one of the heaviest badass drum breaks ever committed to record — the crowning moment of his first benchmark as a solo artist, In the Air Tonight. (We’ll give you a moment to finish power-air drumming along to it.)

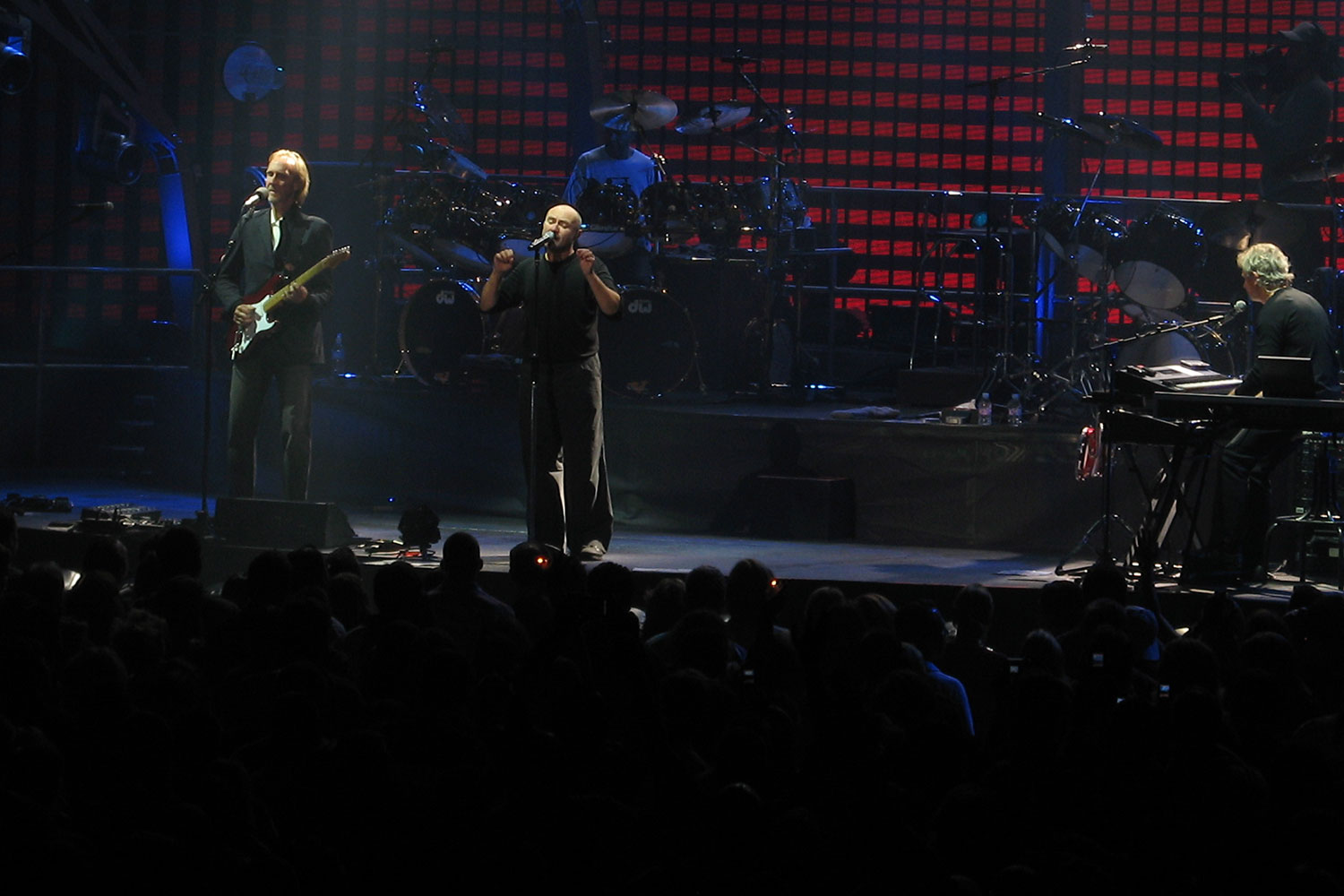

The man’s drum breaks and beats have been sampled on scores of rap and EDM tracks too numerous to count, and his work behind both kit and microphone with the seminal British collective Genesis set the template for how to successfully merge progressive-rock roots with pop aspirations in the ’70s and ’80s.

Collins’ deeply personal style of songwriting has influenced a wide swath of artists ranging from Kanye to Sleigh Bells. With his solo reissue series Take a Look at Me Now currently in full swing thanks to the dual salvo of 1981’s Face Value and 1993’s Both Sides (with 1982’s Hello, I Must Be Going and 1996’s Dance Into the Light to follow on February 26), Collins hopes to reach a new generation of listeners.

“The reason we’re doing this now is because people missed stuff,” he told Digital Trends. “It’s an opportunity to rediscover these albums, or discover them for the first time. And also because of the newer, younger artists who list me as an influence, I think of the young kids who go, ‘Well, OK, who is this guy?’”

Phil sat down with Digital Trends in a hotel room in New York to discuss the sonic choices being made for the reissue series, the most often overlooked innovation in the mix of In the Air Tonight, and the secrets of truly working solo. I saw it with my own two eyes …

Digital Trends: Did you get together with your remastering engineer Nick Davis and have a conversation beforehand about how you wanted these classic albums to sound today?

Phil Collins: Not really. Nick was involved with all the Genesis remasters, and he worked with us [as co-producer] on We Can’t Dance (1991), and also with [Genesis keyboardist] Tony Banks before on his solo projects. We trusted him. When it came to the remastering, I wouldn’t necessarily trust myself, you know?

Why not? Did you feel you were too close to the music yourself?

Not necessarily that, but I haven’t produced anything for a long time, so I left the remastering to Nick and to Miles Showell at Abbey Road. Nick’s a great producer and engineer, and Miles does this for a living at Abbey Road. My criteria is more based on performance. I know the sound can be taken care of.

And you’re also cutting 180-gram vinyl for these reissues.

I mourn the loss of the ceremonious listening to records.

Just yesterday, Nick said, “Is this side break OK for the vinyl?” There are so many questions. The lead-in time for vinyl cutting is incredibly long, because there are very few places that do it nowadays. It’s crazy. We’re working so far ahead, so I’m glad I’m delegating it to Nick, because I’ve been spending my time selecting the live material and all the demos for the bonus discs.

I just got an email from Nick saying, “These are some of the demos I’ve chosen; give me your choice of which ones you like, and which ones you don’t.” I mean, there’s loads of material. I’m not like a Neil Young, who releases everything (smiles), but there are a lot of versions of different things. He’s gone through a lot of it, and selected the best three or four versions of each song for me to pick from.

Were you always a fan of vinyl?

Oh yeah — it was the way we grew up. Of course, I mourn continuously the loss of the 12-inch format of the cover, and the ceremonious listening of the record, you know. You held the cover, and you read the sleeve notes.

It seems to have had a bit of a revival of late, though. Have you seen your kids get into it?

Oh yeah! My son Nicholas — he hasn’t got a record player, but he’s got vinyl on his wall, as decorations. And I’ve got some more for him to take back to Miami.

I think the move from two-sided vinyl to the CD had a big impact on the industry because of the way people listen and the way people buy. I think people got fed up with buying albums that weren’t as big a piece of collective work as they were before.

Right, because then you had albums going from the standard 40-plus minutes up to beyond 70 minutes.

Yeah, and there was a bit of material that was substandard, maybe, that wouldn’t have made an album before.

People stopped knowing how to edit themselves. You used to have 20 minutes per side and you had to worry about where the bass might get lost depending on where the groove was going to be, and also the sequencing.

And you also played mind games with the audience. You had a great side closer so they’d want to turn it over. With CDs, it all went on one side, so people started to say, “Hey, I’m not going to buy an album that’s only got three or four good songs at the beginning, and the rest I could do without. I’ll just buy the three or four songs.” And so it goes, and the whole business changes.

Personally, I have fond memories of putting a coin on the needle to stop it from jumping. (smiles)

You had one of those big Grundig consoles with the lid that closed when you were growing up.

Yeah, yeah, I used to play drums with that behind me playing, so that I could play along to the records that I loved.

Speaking of playing along to records, many of us did that with In the Air Tonight, the iconic opening track to Face Value. It’s taken on such an incredible mantle over the years. We’ve heard that song many time, but I always marvel at how the volume swells that much louder when that drum break kicked in. Did you know it was going to have such an impact?

We didn’t know at the time, but we thought it was good, obviously. There were different stages for that song. When we had Eric Clapton and some of his guys come up to the studio, we played In the Air Tonight for them. When the drums came in, everybody said, “FUCKING HELL! What the fuck is that?” Nobody had ever heard anything like that. Frankly, drums were never that loud. But it was my album, and it worked.

You use inflection and psychological warfare to bring the audience into the story.

We were playing with psychological things. The audience is there going along with you, and then suddenly you knock them on the head with this thing: Bvoom-bvoom!

I had Eric come down to the studio to re-record the [Face Value] song, The Roof Is Leaking. And I missed the plot there — I lost the plot, really. What he does on that song’s demo — you can hear it on the [Extra Values] bonus disc, mastered from a cassette — is what it should be, and also what he did in the studio is what it should be. I had wanted him to do the same thing each time.

But that’s not who he is as a player.

He’s not that guy! (chuckles) It was my mistake, and I don’t know what the fuck I was thinking about. Eventually, I got someone [Joe Partridge] to do the same thing every time, but he doesn’t have the “thing” that Eric does.

Well, I’m glad we now get access to the original demo to hear Eric’s take on it. As a content creator, are you OK with the streaming universe?

I understand it. I just hope that people will rediscover the generation of making an album. I mean, there are no songs on my records that I consider fillers.

It’s like you’re writing a novel, which is how I view what you did on Both Sides — it’s like a well plotted novel with a beginning, middle, and end.

Yeah, well, thank you. I assume that’s a compliment. I shall take it as one.

It is. Even the fans didn’t spend the time with Both Sides like they did with Face Value. Going back to it myself, I liked rediscovering a song like Survivors, and I love where it appears in the running order to help tell the overall story.

Yeah, it’s interesting you saw it like that. I just put the songs in an order that worked when you listened to it, as opposed to, “This is what happened, and then this is what happened.” But records are all things to all people.

As you shifted into your solo career, the emphasis in the mixes became more about your voice and having us hear the emotion throughout different parts of the songs, and where you chose to place inflections for what you intended us to hear and feel.

The audience is there going along with you, and then suddenly you knock them on the head.

I don’t know, did I do that? (laughs) You’ve obviously been listening. But like you said earlier, it’s like writing a novel. There are certain songs like The Roof Is Leaking, which is more of a story song. You use inflection and psychological warfare with the audience to bring them into the story.

And then you have a song like Both Sides’ I’ve Forgotten Everything, which is essentially vocal improv off the top of your head, right?

My memory says most of those lyrics came to me like, “Oh my God, I’ve just said this.” Obviously, I would have had to have filled in a few gaps, but the main part of that one is, I just sang it, and I kept it. And then I came in and out of lines I didn’t have, once I’d written them.

Both Sides is truly a solo album; you played every instrument on it yourself. The Akai 12-track recorder was your closest friend on that record.

Yep, I know! I can’t remember why I started using it, but it was the thing at the time, and it gave me four more tracks than I was used to, you know? And then I had three ADATs that were running in tandem. I had stereo keyboards, and a drum machine that was just a placeholder in some songs and crucial in others.

For example, it would be impossible for a drummer to play I’ve Forgotten Everything. It’s impossible. You’d put things in there you wouldn’t want. It has to stay hypnotic. That album is chock full of my favorite songs, yeah.

And then you get to a song like Can’t Turn Back the Years, which has some added meaning all these years later.

Yeah, yeah, it was written about a very personal situation I was going through.

You’ve never been afraid to put that out there.

No, no. It’s what I do. To me, surely, that’s the way you write songs. It’s what you think, what you feel, and what you believe what’s happening to you. It is personal.